Man up

Man up

- August 25, 2016

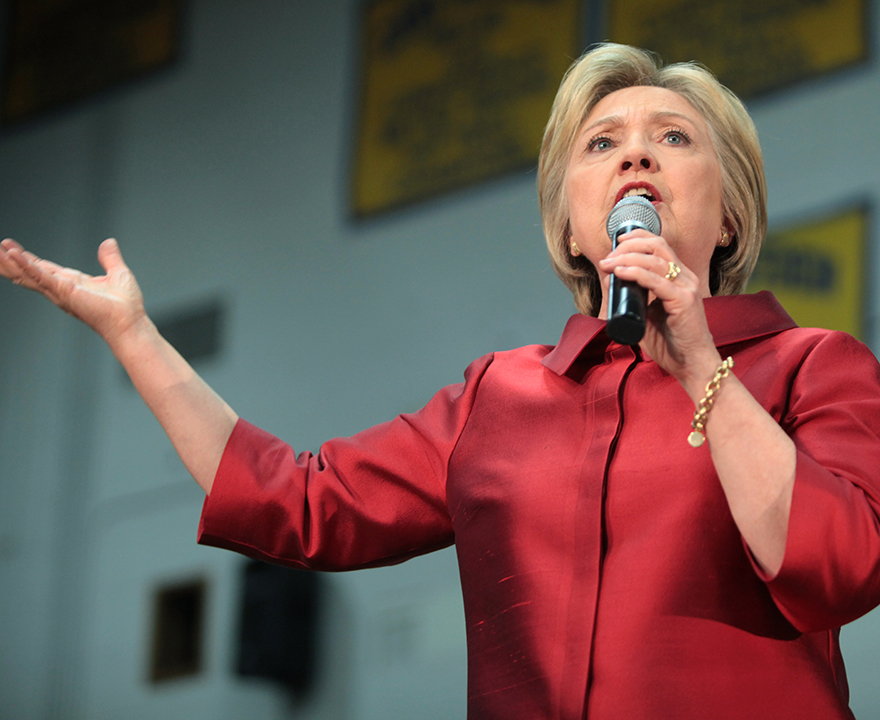

- Poli sci grad student finds evidence that talking “like a man” is a part of Clinton’s political strategy

-----

“It’s not what you say, it’s how you say it.’”

“It’s not what you say, it’s how you say it.’”

Most of us have heard the adage, which typically calls to mind inauthentic apologies or other conversational wrongdoings. But political science graduate student Jennifer Jones believes that her recently published study provides scientific evidence that the rule may also apply to politicians—specifically the Democratic Party’s presidential nominee, Hillary Clinton.

In a recently published article for the Washington Post, Jones summarizes her paper’s findings that claim Clinton’s speech patterns have shifted from feminine to more masculine as she’s advanced her political career, from campaigning First Lady, to U.S. Senator, to Secretary of State. Essentially, though her stance may have remained the same, the way that she speaks about a given issue has changed dramatically.

Jones’ study relies on masculine and feminine language patterns as outlined by social psychologist James Pennebaker in his book “The Secret Life of Pronouns.” In it, Pennebaker looks at the significance of function words in the English language—pronouns (her, him it), prepositions (on, across, up), articles (the, an, a), etc.—and what their use says about the person speaking.

He writes that feminine speakers tend to use more pronouns, verbs and emotion words. They also may use tentative language (i.e. “I think” or “maybe”) and focus the conversation around people. Masculine speakers on the other hand, refer to concrete objects more frequently, use big words (six or more letters), and use more articles and prepositions.

Taking that information, Jones studied more than 500 interviews and debates that Clinton participated in between 1992 and 2013 (she omitted prepared speeches from the study). After analyzing and graphing her data, she was able to see a very obvious shift; as Clinton became more politically involved, her language became increasingly masculine.

“I was surprised,” Jones says. “Not because it went against my expectations, but because I wasn’t convinced of the methodology at first. I was a skeptic. So applying it and finding that these things really held true piqued my interest.”

So what does this say about women in politics as a whole? Jones can’t speak definitively, but if she had to guess, it has to do with a lot. Particularly the “double bind” that female politicians face: If they speak and behave femininely, they’re considered less competent. If they act masculine, they’re not considered warm enough and are disliked.

This issue is evident in her data from late 2007 to early 2008, when Clinton was still a front-runner to be the Democratic Party’s presidential nominee. At first, she was confused by the change in Clinton’s speech patterns, which up until that point had been steadily masculine.

“Once December 2007 comes around, and throughout the rest of the campaign period, it’s just a scatter shot,” Jones says. “Her language goes all over the board. I was really confused by those findings so I went back and did a thorough investigation of her campaign strategies. And her campaign strategy actually changed right at that time that I saw in the data.”

Those who remember this campaign may recall that, at the time, Clinton was receiving harsh criticism and low “likeability” ratings for being too masculine and downplaying her female identity. So her camp decided to change strategies to be perceived as a bit warmer and more feminine. The fact that this change was immediately evident, solely based on the function words Clinton used in interviews and debates, is particularly interesting to Jones.

But the real question she hopes to answer one day is why it’s necessary for female politicians to put on the act in the first place. She’s already taken cursory steps to study public reaction to male and female language, and the initial results show that feminine language is, surprisingly, preferred.

“I found that people in general prefer feminine language,” she says. “They found it to be warmer and they didn’t find it to be less competent, which actually beats the double bind that women in leadership and politics face. So it seems that it’s not the language, it’s the identity. There are a lot of factors that make this up but it’s the female identity that I believe is driving the double bind.”

Moving forward, she wants to take a closer look at these perceptions, and she also will be expanding on the Clinton study to include more leaders of both genders. Eventually she hopes that it may have an effect on the way female politicians feel like they have to behave in order to be successful.

“I think that women recognize the double bind problem and they make a very strategic calculation,” Jones says. “They adopt a persona of what they think a politician is supposed to be like, and what we think a politician should be is a man. It’s an unfortunate reality of history.

“So women change their language and men do not. And I don’t see why that’s necessary. There’s a lot of room to investigate further, but ultimately I think the women should speak like women and it shouldn’t affect the way they are perceived. And maybe we need to have a woman in power to be accepting of that.”

Jones’ article, “Talk ‘Like a Man’: The Linguistic Styles of Hillary Clinton, 1992–2013” has been published in Perspectives on Politics and will be free of charge online until Sept. 6.

-Bria Balliet, UCI School of Social Sciences

-photo by Gage Skidmore

-----

Would you like to get more involved with the social sciences? Email us at communications@socsci.uci.edu to connect.

Share on:

Related News Items

- Careet RightReady for takeoff

- Careet Right3 generations, 1 party: How Clinton, AOC and Gen Z are reshaping the DNC

- Careet RightAttending the National Conference for Black Political Scientists

- Careet RightUC Irvine political science faculty statement on the events of Jan. 6, 2021

- Careet RightHundreds of political scientists call for removing Trump