Fieldwork funded

When Emily Matteson booked her latest flight to Santiago, Chile, she initiated the

newest phase of her fieldwork studying abortion rights claims and access to reproductive

healthcare. However, this trip was going to be remarkably different for the doctoral

student at the University of California, Irvine.

When Emily Matteson booked her latest flight to Santiago, Chile, she initiated the

newest phase of her fieldwork studying abortion rights claims and access to reproductive

healthcare. However, this trip was going to be remarkably different for the doctoral

student at the University of California, Irvine.

She was packing her bags for an entire year, having received the backing of a comprehensive National Science Foundation (NSF) grant to support her ethnographic fieldwork through August 2020. In addition, she earned a grant from the Fulbright-Hays Doctoral Dissertation Research Abroad Program.

Doctoral students in UCI’s Department of Anthropology are guaranteed at least six years of funding, and Ph.D. candidates in the department have been very successful in securing prominent extramural funding to support their fieldwork year. For Matteson, that’s where the NSF and Fulbright-Hays grants come in.

“The department actively works with students to think about their project design, methods, and how to situate their project within relevant literatures and conversations,” she says. “And you get this support from both faculty and peers as you write your grants.”

Power of community

That ethos of support and collaboration extends community-wide, something that Matteson first glimpsed when she visited UCI as a prospective student.

“Not only is the Department of Anthropology one of the top programs in the U.S., it also has a really strong community feel,” she says. “For me, it was important to be part of a supportive and collaborative community, especially if I was going to dedicate six or seven years of my life working toward a Ph.D.”

In her third year, smaller grant-writing groups dotted Matteson’s cohort. She appreciated the organic collaboration with a couple peers and the studious editing process.

“It also strengthens your own skills, as so many of us hope to work in academia in the future,” she says. “You’re practicing effective ways to edit your peers’ work, give feedback and ask insightful questions.”

Essential expertise

Matteson brings years of preparation to the prominence of the NSF and Fulbright Program awards.

She is fluent in Spanish, which she first started studying as a high-school student in California’s Central Valley. After three prior stays in Chile, she knows to expect the very fast cadence of Chilean Spanish speakers, whirring through the language so rapidly that they cut off the ends of a lot of words.

Her first trip to Chile was in 2012 when she was an undergraduate student at Scripps College. Matteson’s semester-long study abroad program was based in Valparaíso, the same coastal city where she currently is living, within commuting distance of Santiago, the capital. Back in 2012, the program had an anthropological focus and examined cultural identity, social justice and community development.

“It was looking at social and political issues in Chile today in relationship to the end of the dictatorship in 1990 and the transition to democracy. Even though almost 30 years have passed, this period has a major impact on society, as we can see through the current nationwide protests over economic inequality,” she says. “The dictatorship and its immediate aftermath are very present in the lives of Chileans today.”

Noteworthy conversations

Matteson’s undergraduate studies also included research on reproductive issues in Chile.

“I’ve always been interested in the anthropology of reproduction and studies of menstruation, pregnancy and birth,” she says.

As she started applying to graduate school in 2015, she was tracking conversations that the Chilean government had taken up to decriminalize abortion under “tres causales,” or three causes: where the mother’s health is at risk, the fetus is inviable or the pregnancy is the result of rape. The discussions were significant considering the country had maintained a complete ban on abortion since 1989.

Matteson focused on the topic for her project proposal for graduate school.

Her UCI faculty advisor and chair of her dissertation committee, Angela Jenks, noted how the continuity in Matteson’s academic interests has strengthened her doctoral research.

“Her work is at the nexus of medical anthropology, feminist studies of science and medicine, and legal anthropology. While she’s looking at issues that are relevant all over the world, she is also closely focused on what’s happening in Chile,” says Jenks, associate professor of teaching and director of undergraduate studies in UCI’s Department of Anthropology. “She has had a long-term engagement with the area and has maintained relationships with people there.”

Legal maneuvers

Legal maneuvers

When Matteson traveled to Chile during her summer break in 2017, the proposed “Law of Three Causes” had gained traction. Her research included hearing senators debate the legislation in real time.

Her apartment was just a few blocks from the congressional building in Valparaíso and she would go sit in the public balcony of Congress. She got to observe the legislators below, as well as the anti-abortion and abortion-rights activists who were shuttled into separate areas of the gallery.

By the end of that summer, the “Law of Three Causes” had been approved.

“It’s important to remember as well that only 3 percent of Chilean women seeking abortion services actually fall under the law,” Matteson says.

The law’s relevance was poised to narrow further. Legislators had added a conscientious objection clause, an exit for medical practitioners — including those at private hospitals and clinics — to refuse to provide abortion services.

In the subsequent two years, “throughout Chile, extremely high rates of doctors are claiming conscientious objection on one or more of those causes — with rape being the largest case that doctors are objecting against,” Matteson says.

Widespread dissent

Abortion-rights activists and some politicians are continuing to work to expand reproductive rights in Chile. They’re advocating for women to be able to access abortion services without the limits of the three causes, similar to federal policy in the United States, Matteson says.

On the other side, Catholics and evangelical Christians are “definitely a strong voice in the conversation,” she says. “Even if people aren’t actively practicing Catholicism, the society is heavily shaped by those influences. And right now the president and government is more conservative.”

More than 65 percent of the Chilean population is Roman Catholic, and another 16 percent is evangelical or Protestant, according to the CIA World Factbook.

Across Latin America, views on abortion access are shifting in what has been dubbed a “green tide” — a reference to the green bandanas that people wear in support of abortion rights. In late September, the green tide movement made headlines in Oaxaca, Mexico, when the state legislature legalized first-trimester abortions.

Diligent research

Diligent research

As part of her archival research, Matteson studies green tide imagery in tandem with materials awash with anti-abortion activists’ equivalent: “celeste,” or light-blue, bandanas. She combs through social media posts, gathering digital artifacts that represent different groups. At marches and rallies, she chronicles activists’ posters and artwork.

She is even more keen to talk with people who she meets at events and through her growing network. During her fieldwork year, Matteson plans to interview a wide range of Chilean women, reproductive-rights NGOs, anti-abortion activists, doctors who have or have not claimed conscientious objection, policymakers and feminist activist groups.

“Most of the time, when people hear what I’m studying, they’re interested and want to help by sharing their experiences and opinions,” she says. “And talking to people is the best way to expand your contacts and your connections here.”

Faculty advisor Jenks highlighted Matteson’s effectiveness as a communicator as key to her ethnographic insights.

“She’s able to develop a rapport with people to talk about deeply personal issues, such as pregnancy and abortion,” Jenks says. “Her ethnographic skills have helped her succeed. Those are some of the very skills that UCI’s Department of Anthropology seeks to help students develop.”

After her year of fieldwork, Matteson looks forward to supporting that priority, especially by speaking to UCI’s dynamic undergraduate anthropology club and the students she works with as a teaching assistant.

“I really enjoy teaching at UCI, and it’s exciting to think about coming back to campus and getting to share some of my experience from my dissertation research in Chile,” she says. “In the future, hopefully I’ll be working at a college or university where I can continue to study reproductive health issues. But I hope to always be connected to Chile.”

-Kiali Wong Orlowski for UCI School of Social Sciences

-Top photo: Cable car in San Cristobal hill, overlooking a panoramic view of Santiago

de Chile. tifonimages/istock

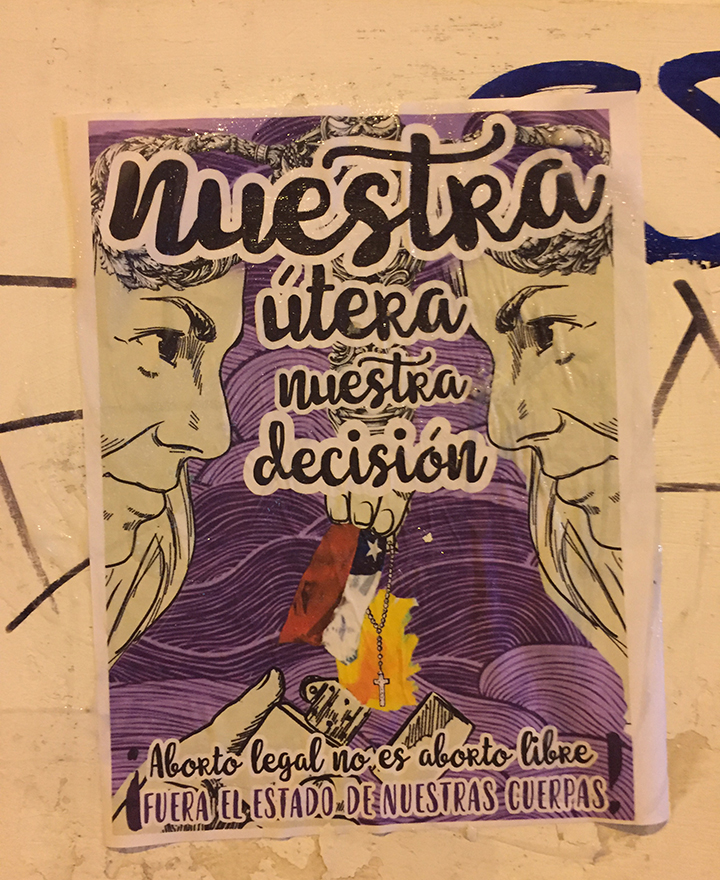

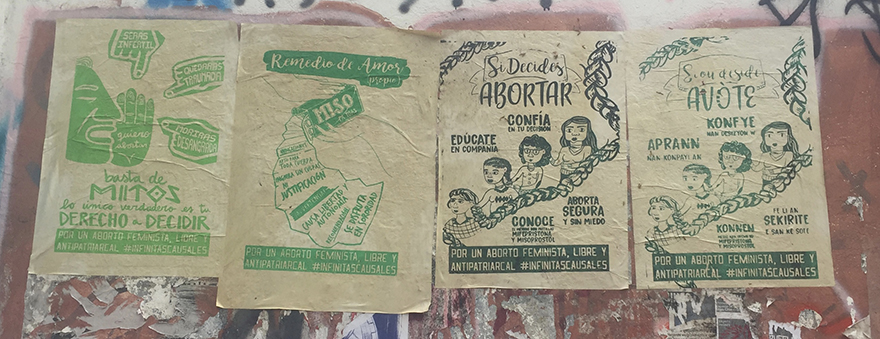

-Interior photos courtesy of Emily Matteson. From top right: (1) Matteson, an anthropology

doctoral student at UCI. (2) Artwork that promoted “nuestra útera, nuestra decisión”

(“our womb, our decision”) was glued to the walls of businesses during an abortion

rights march in Valparaíso. (3) Multiple flyers that Matteson found posted in Santiago

after an abortion rally.