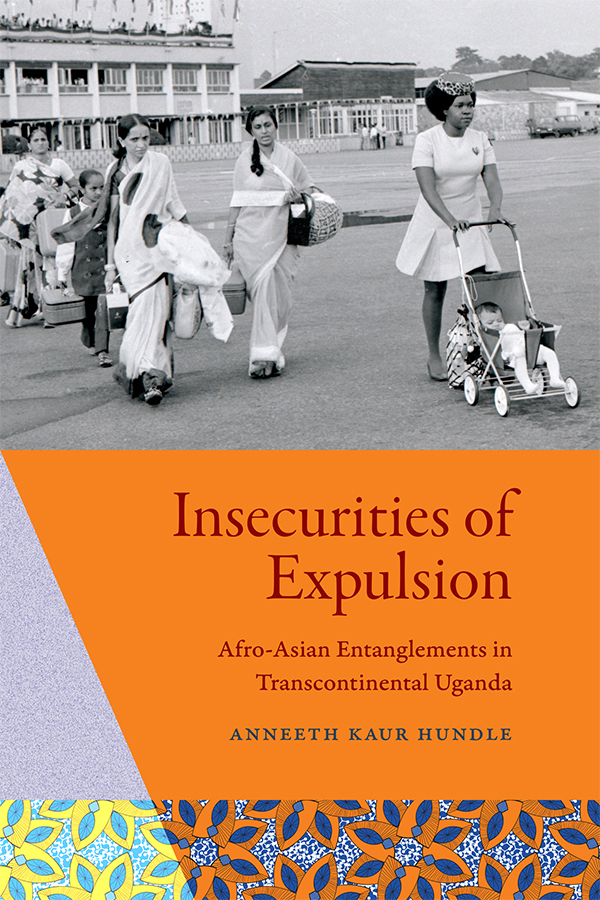

Insecurities of Expulsion: Afro-Asian Entanglements in Transcontinental Uganda

In her new book, Insecurities of Expulsion: Afro-Asian Entanglements in Transcontinental Uganda (Duke University Press), UC Irvine anthropologist Anneeth Kaur Hundle examines the

1972 expulsion of South Asians from Uganda and its lasting consequences. Below, she

reflects on the historical and contemporary stakes of the expulsion, the complexities

of Afro-Asian connections, and what her research reveals about citizenship, belonging,

and reconciliation in postcolonial contexts.

In her new book, Insecurities of Expulsion: Afro-Asian Entanglements in Transcontinental Uganda (Duke University Press), UC Irvine anthropologist Anneeth Kaur Hundle examines the

1972 expulsion of South Asians from Uganda and its lasting consequences. Below, she

reflects on the historical and contemporary stakes of the expulsion, the complexities

of Afro-Asian connections, and what her research reveals about citizenship, belonging,

and reconciliation in postcolonial contexts.

Q: How did the 1972 expulsion of South Asians from Uganda emerge as a focal point for your research, and what intellectual or historical questions guided your study?

A: In the diasporic community I grew up in, I was always vaguely aware of the imperial entanglements between South Asians and Africans, of African-origin Punjabi Sikhs who had migrated out of East Africa and who had been displaced by new postcolonial East African nationalist policies, or who had been expelled more suddenly in Uganda. In addition, I grew up in the Chicago-land area and had exposure to Black American and African diasporic history and communities, so I was interested in general in Black-South Asian, and Black-Punjabi Sikh connections specifically. As an undergraduate anthropology student, I chose to forgo research in the Indian Punjab and instead pursued senior thesis research on the experiences of Asian or Indian women (expatriates and return migrants and new migrants) in urban Uganda. I focused on how they experienced community patriarchies, and in relation to tense race relations with the majoritarian Black African community after the 1972 Asian expulsion. This research gradually became the basis for my doctoral work.

I realized that I needed to explore both the historical processes that led to the event of the 1972 Asian expulsion (the mass displacement of 80,000 Ugandan Asians by dictatorial decree by President Idi Amin) as well as its aftermaths, in order to better understand the politics and practices of citizenship. If multiracialism or nonracialism were ideals for postcolonial democratic nation-building in places like Tanzania and South Africa, what models of citizenship guided Ugandan nation-building after the expulsion? What accounted for new Indian migration and settlement in the nation, and how was the expulsion understood now?

In general, my research was animated by three guiding questions: 1.) what is the relationship between event (the expulsion) and national and diasporic memory (both collective and individual), the event and the everyday, the event and discourse, ideology and representation?; 2.) how do we understand the politics and practice of citizenship, sovereignty and governance after such a historical rupture occurs?; and 3.) what does this research mean for a broader theorization of Afro-South Asian connections, or what I call “an anthropology of Afro-Asian entanglements?”. These questions also speak to how we can bring both anthropological and historical research—ethnography and other archives beyond the colonial--to bear on each other in creative ways.

Q: Your book challenges dominant narratives that frame the expulsion as either a singular historical rupture or a simplistic racial conflict. What did your research reveal about the longer-term, more complex entanglements between African and South Asian communities in Uganda and beyond?

A: Much of the scholarship that I read about this mass expulsion event seemed to peter out by the late 1970s. There was a sense of “postcolonial closure” around the event in Kampala—an idea that the displaced had moved on with their lives in the diaspora and assimilated to Western liberal nations, and that South Asian-ness—and an engagement with race and racial dynamics—was no longer at the center of scholarship on Uganda, much of which had adopted the framework of African ethnicity to attend to war and conflict in the years after the expulsion. I also began to contrast Uganda-based national memory surrounding the expulsion and popular global representations and diasporic memory surrounding the event. In Uganda, there was little to no public discussion of the event and its aftermaths. But in its global circulations, there seemed to be a sense of spectacularity and exceptionalism surrounding the expulsion, often decontextualized from historical context. This exceptionalism seemed to construct ideas of primordial Afro-Asian racial conflict, and even of an inherently liberal and civilized West, as opposed to an illiberal and uncivilized Black Africa, incapable of norms of liberal-democratic citizenship and multiracialism.

In reality, I found that various expulsions took place in post-independence Uganda and across the African continent in the context of nation-building, and that this expulsion was not necessarily exceptional. It was, however, a unique racial event, (with a lot of diasporic baggage!) and I was intrigued by the fact that the expulsion and its aftermaths had not been taken more seriously in fields of study like South Asian and African diaspora studies, despite what it reveals about complicated and uneasy histories and enduring racial tensions, citizenship and even the limitations of a politics of reconciliation in the aftermath of 1972.

Q: In examining what you call “transcontinental Uganda,” you draw on multiple social dimensions—race, caste, gender, class, religion. How did this multidimensional approach shape your understanding of citizenship and belonging in post-expulsion East Africa?

A: I was trained as a feminist anthropologist, and wanted to bring feminist approaches to bear on my research and analysis. I was concerned that the emphasis on colonial hierarchies of race and labor-capital relations and class to explain racial conflict in postcolonial Uganda sidelined the significance of patriarchy as foundational to African and South Asian indigenous societies and colonial and postcolonial governance. So, for example, in existing scholarship that explores Afro-Asian racial conflict and attempts at multiracial nation-building, racial communities often came to be represented by men involved in nationalist politics.

But how are communities actually formed? By bringing the lives of Asian and African women into view, I explored instances of interracial marriages and transnational marriage and kinship systems and patriarchy, as well as religious and caste-based norms as the basis of endogamous racial and community boundaries—and by extension, racial tensions between Indian communities and Black African communities.

“Transcontinental Uganda” is also a feminist concept. I wanted to shape an understanding of my research location as not somewhere “out there” in an illiberal Africa, but to think of it as a major global center for working through Afro-South Asian encounter and the accumulating histories of precolonial Indian Oceanic connection, empire and colonialism, nationalism and postcolonialism, transnationalism and diasporic migration and displacement, geopolitical change—in other words, what we understand as Ugandan nationalism is also shaped by transcontinental geographies and histories, including Indian Oceanic and Black Atlantic connections to South Asia, Europe and North America— thus offering possibilities for studying Afro-Asian entanglements and the possibilities and limitations of interracial pluralism beyond national exclusion.

Q: What are the broader implications of your work for how we think about diaspora, displacement, citizenship and postcolonial nationhood—both within Africa and globally?

A: We often think about diaspora communities as isolated or even deracinated from their origins, or even that diasporas have a single origin. My research revealed that displaced Ugandan Asian diaspora communities were still reckoning with their African (and South Asian) heritage, and that their entanglements with Black African communities were still central to their ideas and claims about diasporic identity, subjectivity and citizenship, even in shifting geopolitical and neoliberal times.

Ugandan Asian returnees who have settled in urban Uganda semi-permanently under a state-led property repossession process in the 1990s, or new migrants from South Asia who are settling in urban Uganda as entrepreneurs and migrants are understood as “investor-citizens”—not fully substantive racial citizens, but often with expatriate, class and economic privilege. The renewed South Asian presence Kampala raises insecurities about a past that is unsettled and the logics of racially nativist nationalism remain intact. Unlike other postcolonial contexts, there has been no formal state-led process of racial reconciliation in Uganda. There have been symbolic, performative or politically strategic gestures, and populist forms of racial nativism and calls to expel minorities continue. It is also true that practices of Indian racism and elitism against Africans continue to persist, suggesting that minority groups in majoritarian postcolony/nation can also be privileged—and can even contribute to their own racial community’s precarity--in a transcontinental world.

Q: Looking ahead, what do you hope scholars, policymakers, or readers take away from this book? What kinds of conversations or actions would you like this research to spark?

A: I hope my book raises several conversations across diverse audiences: that historical events that we think are settled remain unsettled and continue to accumulate, becoming part of everyday life and politics; that practices of citizenship, exclusion and belonging vary according to different contexts and require their own conceptual universe; that conflict can be accompanied with an ambivalent politics of non-reconciliation and as scholars we must dwell in that ambiguity and attempt to write about it; that studying co-colonized racialized communities is important work and requires rethinking of discipline and area studies; and that horizons for reconciliation and healing, co-liberation, and Afro-Asian universalisms need to be made legible and assessed through careful research-not only utopian ideals.

More immediately, I hope my research sparks continued interest in Black-South Asian connections—both intimacies and estrangements—and possibilities for envisioning a creative diasporic politics in authoritarian times here in the US and other contexts that are officially still understood as liberal democracies. Creeping authoritarianism here in the US, of course, mimics the politics of nationalism, fascism and racial expulsion in post-independence Uganda—so we can all learn from postcolonial Uganda. Some of my next work will be exploring the politics of mass expulsion through the lens of both Donald Trump and Idi Amin, placing imperial and postcolonial fascisms in the same relational frame.