Teaching the whole story

Teaching the whole story

- October 29, 2025

- Through their contributions to the High School Ethnic Studies Resource Book and their nonprofit, Educate to Empower, UC Irvine alumnae Virginia Nguyen and Stacy Yung are reshaping how students see themselves

-----

In the early days of the pandemic, Virginia Nguyen (B.A. political science and sociology ’01; M.A.T. ’03) and Stacy Yung (B.A. social sciences ’07; M.A.T. ’09) were teaching through more than screen fatigue and Zoom malfunctions. Their middle

school and high school students in Irvine were trying to make sense of a world in

turmoil. The violence that preceded the Black Lives Matter movement, the rise in anti-Asian

hate, and a constant stream of public grief began filtering into classroom discussions,

even when they weren’t part of the lesson plan.

In the early days of the pandemic, Virginia Nguyen (B.A. political science and sociology ’01; M.A.T. ’03) and Stacy Yung (B.A. social sciences ’07; M.A.T. ’09) were teaching through more than screen fatigue and Zoom malfunctions. Their middle

school and high school students in Irvine were trying to make sense of a world in

turmoil. The violence that preceded the Black Lives Matter movement, the rise in anti-Asian

hate, and a constant stream of public grief began filtering into classroom discussions,

even when they weren’t part of the lesson plan.

“Our classrooms became places where the outside world kept making its way in,” Nguyen says. “And our students kept sharing how painful it was to navigate during these times.”

For both teachers, the question became not how to shield students from that pain, but how to help them make sense of it.

“What do we do when our students feel helpless?” Nguyen asks. “We turn to history. We turn to stories of how hardship has been overcome, and how we can be resilient together. That’s the story of ethnic studies.”

At its core, ethnic studies is an academic approach that centers the histories, experiences, and contributions of marginalized communities, particularly Black, Indigenous, Latinx, and Asian American peoples, with the goal of fostering critical thinking, civic engagement, and deeper cultural understanding.

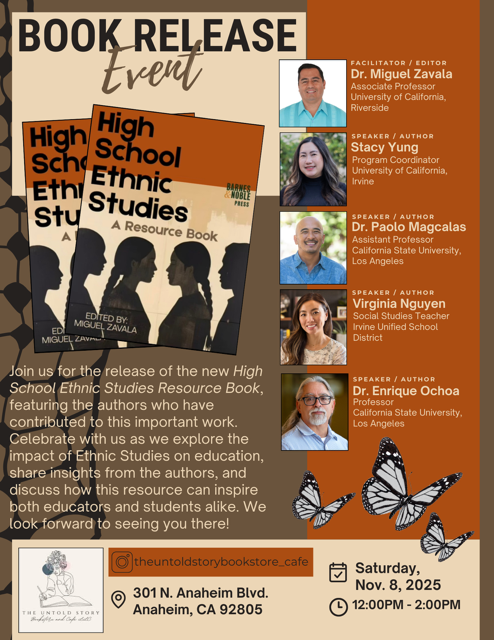

That work takes a new shape this fall with the publication of the High School Ethnic Studies Resource Book, a multi-author collection of community-based models for teaching ethnic studies in schools. The release comes at a pivotal moment. It follows the passage of Assembly Bill 101, which makes ethnic studies a graduation requirement for California high school students beginning with the class of 2029–30. Nguyen and Yung contributed chapters rooted in their ongoing work as co-founders of Educate to Empower, a nonprofit that trains teachers to approach education through a justice-centered, community-responsive lens.

Their efforts have reached beyond the classroom. In recognition of this work, Educate to Empower was named a 2024 PBS SoCal Local Hero and has been featured on NPR for its contributions to equity-focused education.

The High School Ethnic Studies Resource Book will be officially released at a public event on Saturday, November 8, from 12–2 p.m. at The Untold Story Bookstore in Anaheim. And while the publication marks a milestone in their work, their partnership began long before their first drafts were written.

A shared language

Nguyen and Yung didn’t meet during their time at UC Irvine, but years later as teachers in the Irvine Unified School District.

Though they taught at different schools and at different grade levels, they connected in their belief that history invites empathy, and education opens the door to transformation.

Their early collaborations were informal, but as conversations deepened, they saw the need for something more structured. Educate to Empower grew out of that need.

“We kept asking how we can support teachers to see themselves as agents of change,” Yung says.

They began designing interdisciplinary learning experiences rooted in local history—stories that had long been overlooked in standard curriculum. In one set of lessons, students explore the rise and erasure of a Chinese immigrant community in Santa Ana. In another, they examine the resilience of Mexican American and Indigenous Californians who navigated the U.S. annexation of California.

Each lesson aligns with the state’s history standards, but adds specificity, proximity, and depth.

“We’re hoping to deepen what teachers are already teaching by making it more relevant and connected to students’ lives,” Yung says.

Community as curriculum

Nguyen and Yung operate on the principle that teaching doesn’t end at the classroom door. It extends into communities, histories, and public memory. In that spirit, their contributions to another resource, the Educator’s Guide to Orange County, were developed not only with other teachers, but in partnership with UC Irvine Libraries, the UC Irvine History Project, the UC Irvine Teacher Academy, Groundswell, and the Heritage Museum of Orange County.

As part of Educate to Empower, Nguyen and Yung also lead walking tours in Orange County. In one tour, educators retrace stories of displacement and resilience through Little Saigon. In another, they visit the sites of historical erasure in Santa Ana and Westminster. The goal, they explain, isn’t simply to teach history, it’s to help students and educators see themselves within the narrative.

Their work is deeply collaborative and community-based and sustained by a combination of donations, grants, and partnerships that help keep the small, teacher-led initiative going.

“I think for a lot of marginalized communities, students only see themselves in curriculum as victims or as the oppressed,” Yung says. “What we’re trying to do is uplift those stories in ways that humanize, connect, and empower.”

Nguyen sees the impact of that approach firsthand. Whether or not the course is formally labeled “ethnic studies,” she is guided by this perspective every day.

“I’ve never technically taught an ethnic studies class,” she says. “But when I teach, it’s with that lens. Because at the heart of it, it’s about helping students see that their stories belong here too.”

Nguyen and Yung are clear about this: ethnic studies is not just for ethnic studies teachers. And the promise of education cannot be fulfilled by teachers alone.

“We need K–12 education, but it has to be supported by everyone,” Yung says. “We all have a role to play, especially those in the neighborhoods our students return to each day.”

They suggest that could mean asking questions at a school board meeting, inviting scholars into classrooms, or helping students share their family histories as part of the curriculum.

“Imagine a world where everyone—parents, alumni, neighbors, voters—sees themselves as part of what education could be,” Yung says. “That’s the world we’re trying to build.”

Nguyen echoes the same belief.

“There’s so much joy in being around these amazing kids and their dreams,” she says. “I’ve been lucky to learn alongside them. I wish more people could be a part of this too.”

Ongoing work

When asked about the future, both women are quick to clarify that the work isn’t finished, it’s ongoing. It’s rooted in the daily, sometimes invisible labor of classroom teaching.

Nguyen still teaches full time at Portola High School. Yung now serves as the single-subject coordinator for UC Irvine’s MAT program. While she deeply misses the classroom, she continues to visit schools regularly through her work with teacher candidates.

Nguyen and Yung are currently preparing for their annual Teaching for Justice Conference, a two-day gathering in Southern California that centers AAPI histories and lived experiences. The event brings together educators, students, parents, and community leaders dedicated to advancing social justice.

The release of the High School Ethnic Studies Resource Book is a chance to reflect, but also to reaffirm what they already know: that change doesn’t come from policies, textbooks, or curriculum—it comes from people.

“The kids tell us it helps them understand themselves, and their connection to the world, more deeply,” Nguyen says. “Sometimes you don’t need a textbook to do that. Sometimes that story is already being told at the dining table. Someone just needs to say that it matters.”

-Jill Kato for UC Irvine School of Social Sciences

-pictured: Stacy Yung and Virginia Nguyen

-----

Would you like to get more involved with the social sciences? Email us at communications@socsci.uci.edu to connect.

Share on: