Juneteenth

Juneteenth

- June 19, 2023

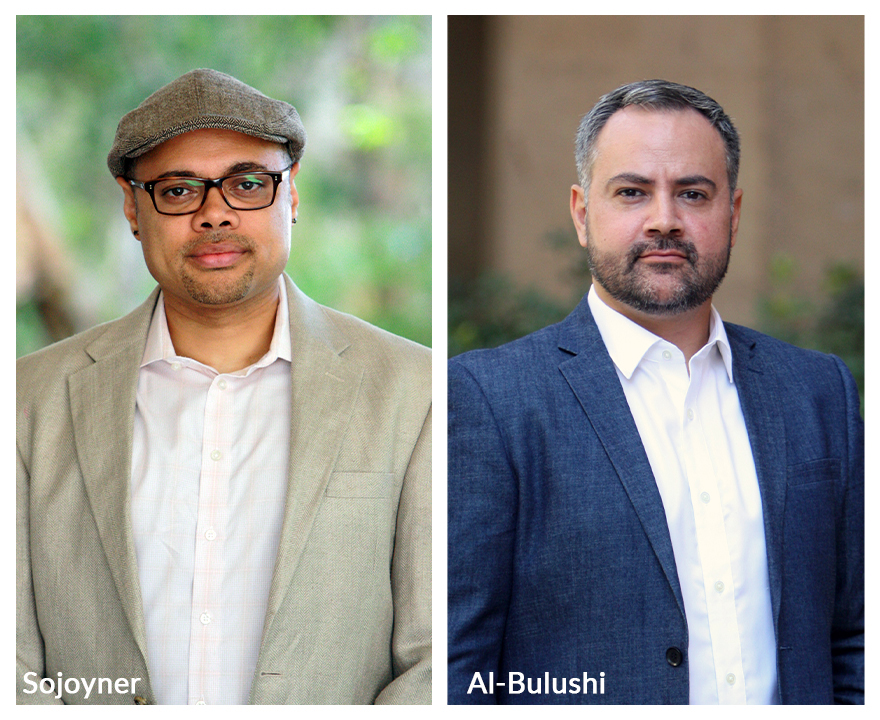

- UCI social scientists Yousuf Al-Bulushi, global and international studies, and Damien Sojoyner, anthropology, provide perspective

-----

When thinking about the importance and salience of Juneteenth during this very important moment, our “go-to” source for analysis has been W.E.B Du Bois’s foundational tome, Black Reconstruction in America. Quite fortuitously, during the past year, we have had the pleasure of hosting a series of panels and discussions funded by the Mellon Foundation, Black Reconstruction as a Portal, with scholars and activists from around the world who have wrestled with intense questions and contradictions that Du Bois lays bare in the text. One of the key themes that was brought forth again and again throughout the year was the need to study the strategies employed by the fractured state apparatus of the United States of America nation project during the middle to late 19th century that provided the means for it to live out its most cruel imperial political ambitions throughout the 20th and 21st centuries.

Using the methodological impulse undertaken by Du Bois, it was understood by virtually all the series participants that the veneer of progress and advancement that was trumpeted throughout channels of state life (such as education, media, and the legal apparatus) attempted to cover a most vile revanchism. With the veil ever-so-slightly lifted, what was revealed was the true reactionary nature of political and economic power brokers who forged a most violent statecraft endeavor. Utilizing various forms of forced labor, incarceration, workhouses, and land grabs, the United States - as many imperial projects are wont-to-do – codified such acts into law as a means to establish a civil apparatus built upon the shaky ground of a racial capitalist hellscape. The wealthy white men proponents of the United States project utilized Reconstruction as a key register to support the veneer of social progress during the early 20th century. However, as Du Bois notes, Reconstruction was anything but a bastion of human progress, writing, “Then came this battle called the Civil War, beginning in Kansas in 1854, and ending in the presidential election of 1876 – twenty awful years. The slave went free; stood a brief moment in the sun; then moved back again toward slavery.”

And thus we are brought back to Juneteenth. A celebration that was mostly unknown outside of the southern and western Black population of the United States, Juneteenth was suddenly thrust into the national spotlight and then made a holiday in the wake of the uprisings marked by the murder of George Floyd. This was the most curious timing. Juneteenth suddenly represented a political and symbolic moment that had transformed its actual cultural practice enacted by Black populations in the United States. Marked by social gatherings in neighborhood parks, on HBCU campuses and in Black church sites of worship, Juneteenth was most commonly a day of festive eating, music, and spirited game playing. Not that the political importance of the day was forgotten upon Black people who gathered in these Black spaces, but as the well-traveled meme states: “This ain’t that.”

Following the impulse of Du Bois’s method and theory in Black Reconstruction, we find that during this Juneteenth of 2023, it is important to take stock of the events that mark this moment:

- There have been over 400 anti-LGBTQ bills introduced into state legislatures across the United States since January 1st, 2023.

- Since 2021, 19 states have passed laws, particularly targeting Black communities, making it difficult to vote and attempting to redistrict congressional seats as a means to suppress Black voters.

- In 2022, the Supreme Court overturned Roe v Wade and gave states the right to decide upon a woman’s right to choose what is best for her reproductive health.

- Following the death of an 8-year-old Black Panamanian child at a US border facility (whose family was denied ambulatory services despite several pleas for help), it was revealed that there have been over 30 deaths at US migrant detention facilities over the past 4 years.

- States that are key production sites of agribusiness and meatpacking operations have passed legislation to undo child labor protections and many large scale businesses have actively sought out child labor.

So how is it possible, 150 years after the Emancipation Proclamation, that the United States and the world at large sits at the crossroads of so many overlapping crises–indeed, of a polycrisis? What explains the rise of neo-fascist and authoritarian movements in so many parts of the world that threaten democracy in all its forms? Du Bois’s Black Reconstruction once again offers us valuable lessons here, highlighting the structural and ongoing nature of “the propaganda of history”--the stories we tell ourselves about our past in order to better interpret the present–and the permanent “counter-revolution of property.”

For Du Bois, liberalism was not an adequate antidote to the threat of fascism. While he admired a number of the white abolitionists leading the struggle for Reconstruction in the US Congress, he also saw the obvious limits at the core of their ideology. As he states: “To men like Charles Sumner, the future of democracy in America depended on bringing the southern revolution to a successful close by accomplishing two things: the making of the black freedmen really free, and the sweeping away of the animosities due to the war.” In this phrase, “really free” means not only the abolition of legal slavery, but also its corollaries in the form of robust rights to vote, to education, and to radical land redistribution.

But the way they hoped to go about this–by peacefully appealing to compromise with a defeated southern plantocracy–was doomed to failure for Du Bois, and evocative of liberalism’s misunderstanding of a structural reality lying beneath the surface of all capitalist societies. “What liberalism did not understand was that such a revolution was economic and involved force. Those who against the public weal have power cannot be expected to yield save to superior power.”

This Juneteenth, then, rather than engage in the perpetuation of the liberal myths that lie at the core of “the propaganda of history” by celebrating the supposed singularity of America and our ability to rise up and overcome–”America is already great”--we should have the courage to look our bleak situation squarely in the eye. And like Du Bois, we should look for possible answers not in the halls of power or among the talking heads on TV and social media, but in the everyday spaces where common people are gathering to confront these threats. There we are likely to find freedom and fugitive dreamers quietly preparing for a rupture with History, for a materialist rapture, for another moment defined by what Du Bois called “The Coming of the Lord.”

Yousuf Al-Bulushi, global and international studies assistant professor, and Damien Sojoyner, anthropology associate professor, co-lead “Black Reconstruction as a Portal," a yearlong series that examines the role Black Americans played in reconstructing American society following the Civil War. Funded by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, the project draws on cross-disciplinary expertise from humanities, law, social ecology and social sciences to critically assess how education, crisis and land remain relevant lenses through which to view ongoing global racial, economic and social issues.

-----

Would you like to get more involved with the social sciences? Email us at communications@socsci.uci.edu to connect.

Share on: