MLK Day reflections

MLK Day reflections

- January 13, 2022

- UCI social scientists offer expert perspective on progress, pitfalls of nation’s efforts toward racial equity, social justice

-----

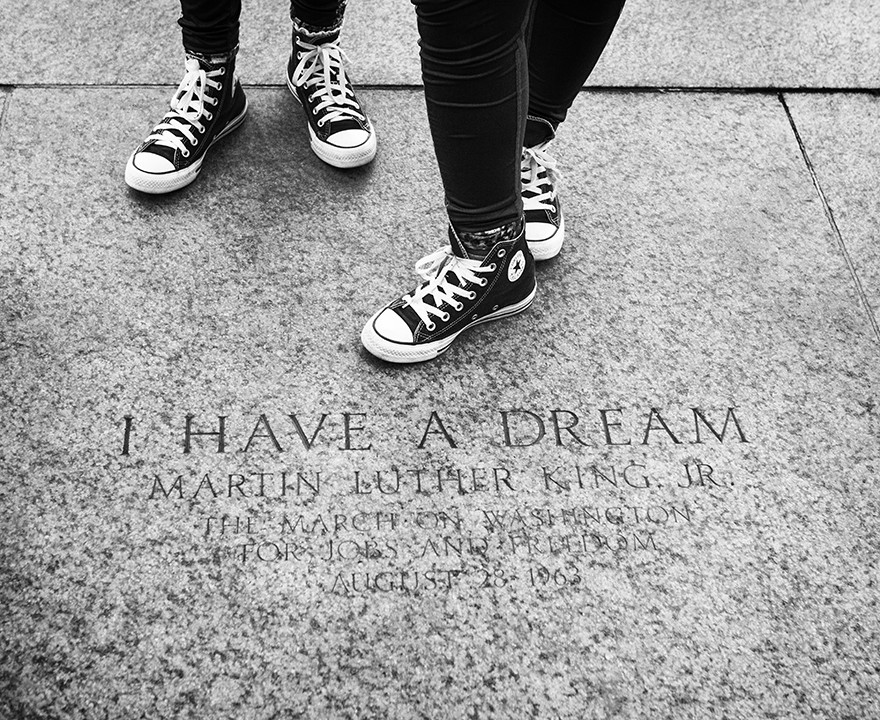

Martin Luther King Jr Day - observed this year on Jan. 17 - offers an annual opportunity to reflect on progress and pitfalls made along the nation's path toward racial equity and social justice. Below, UCI social scientists offer expert perspective on how far we've come and how far we have yet to go to realize the world MLK envisioned.

Davin Phoenix

Associate Professor, Political Science and Inclusive Excellence Term Chair Professor, UCI

My research finds an abundant wellspring of hopefulness about politics expressed by African Americans, whether in anticipation of a milestone like the election of the first Black president, or optimism about a favored local policy passing. This hope propels Black people toward greater political participation. But would such hope waver in the midst of a global pandemic that has taken a disproportionate toll on Black health and economic outcomes? Or in the face of massive protests spurred by police killings of Black people?

From national survey data spanning late 2020 and early 2021, I find African Americans are significantly more hopeful than Whites about the state of race relations. Does this hope indicate faith in American institutions and policymakers to make good on the elusive promise of a true multiracial democracy? Given the absence of a major legislative response to the historic Black Lives Matter protests of 2020, and the continued inability to pass federal voting rights protections in the face of actions impeding Black enfranchisement, I say no. Rather, this hope signifies an unwavering faith in the capacity of Black people themselves to endure injustice. We shouldn’t misread this hope as an indicator of progress toward the vision articulated by King. But rather, a call to action to act urgently to advance a vision of equity that ensures such hope does not prove hollow.

Anita Casavantes Bradford

Associate Dean, Faculty Development and Diversity and Associate Professor, Chicano/Latino

Studies and History, UCI

In his 1963 “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” Martin Luther King addressed those who criticized his commitment to direct action against racial segregation as a threat to law and order. Insisting we have “not only a legal but a moral responsibility to obey just laws,” King also argued that we have an equally pressing obligation to disobey—and work to eradicate—unjust laws.

In my new book, Suffer the Little Children: Child Migration and the Geopolitics of Compassion in the United States, I analyze how the U.S. approach to unaccompanied child migrants has evolved between the 1930s and the present day. Despite its evolution over time, I argue that the treatment of migrant children continues to be governed by a “geopolitics of compassion” that selectively highlights United States benevolence while prioritizing foreign policy and domestic political objectives over asylum seekers’ best interests. What’s more, although U.S. law increasingly acknowledges children’s autonomy and rights, decisions about which unaccompanied child migrants to admit or exclude remain powerfully influenced by an understanding of children as extensions of their parents and communities. This longstanding denial of children’s individual existence underwrote the racialized logic of deterrence that justified barring endangered Jewish children from the United States in 1939, seeing them as an “entering wedge” whose admission would lead to an influx of co-religionist adult refugees. Since the 1980s, it has also inspired frontline immigration officials to undercut unaccompanied Southeast Asian, Haitian, Central American and Mexican minors’ access to asylum, by framing them as “illegal immigrants” and “anchors” despite their demonstrable need for protection.

My research compels me to conclude that our treatment of unaccompanied child migrants—and our immigration and refugee law more broadly—are both ineffective and unjust. Despite this, too many Americans cling to the belief that our immigration system is fair and functional, while avoiding difficult conversations about our role in creating political and economic crises that spark migration from south of our border. Too many deny the humanity of unauthorized border crossers of all ages—most of whom are poor people of color—because they have “broken the law.”

When I consider the history of U.S. immigration and refugee law in light of MLK’s Birmingham letter, it’s clear to me that the still-unrealized struggle for racial justice in the United States cannot be separated from the ongoing movement for immigration reform. Both call upon us to reflect deeply upon the power and fallibility of the laws that govern us—and to work to change them when they deprive others of rights we ourselves hope to enjoy. Both urge us to acknowledge our shared humanity--and to see that “injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.” Without substantive change in both these areas, Martin Luther King’s dream that we will someday realize the ideals of American democracy for all will remain unfulfilled.

Jeffrey Kopstein

Professor, Political Science, UCI and Ina Levine Invitational Scholar, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington

DC

Martin Luther King envisioned a land of racial equality and inclusion. His was a broadly liberal and optimistic vision. But it came with a warning. In his famous “I Have a Dream” speech he referred to the rights enumerated in the U.S. Constitution as a promissory note that had yet to be honored and warned of the dire consequences should it continue to be returned stamped “insufficient funds.” As much as anyone, however, he understood that the beneficiaries of inequality would not easily relinquish their advantage. Decades of research have backed up the point: this moment in the history of multi-ethnic and racial societies, when the prospect of genuine equality becomes possible, even tangible, is the time when majorities often cannot resist the temptation to double-down on their advantage with clever rhetoric, legal manipulation, and exclusionary violence. In our own society, it is a moment that calls for creativity, sensitivity, and determination if we are ever to arrive at the shore of multi-racial democracy.

-----

Would you like to get more involved with the social sciences? Email us at communications@socsci.uci.edu to connect.

Share on:

Related News Items

- Careet RightThe best of books 2025

- Careet RightSubreddits study highlights the hidden ways that hate speech spreads

- Careet RightSecret meanings: Third of QAnon subreddits contain implicit antisemitism - study

- Careet RightMulti-university study maps link between explicit and implicit antisemitic content that circumvents online censorship, social stigma

- Careet RightSins of the Father