Returns of war

Returns of war

- July 25, 2019

- New book by Long T. Bui, UCI assistant professor of global and international studies, tells the living stories, history of South Vietnamese refugees

-----

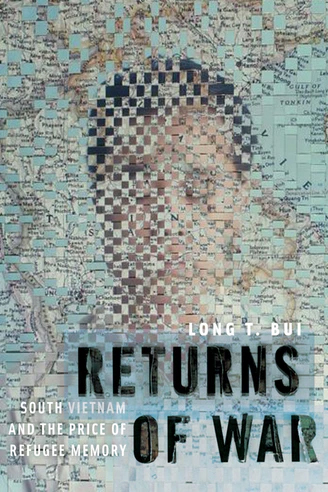

As a Vietnamese American, UCI assistant professor of global and international studies

Long T. Bui grew up learning about his family’s South Vietnamese heritage through an American

history lens. The militaristic narrative left him with many questions about the people

– including his mother and father – who were displaced. He sought their stories through

interviews and analytical research for his new book, Returns of War: South Vietnam and the Price of Refugee Memory. Below, Bui discusses the importance of recording the experiences of those who fled

a nation no longer recognized, but one that’s still very much alive in the memories

of the refugees who once called South Vietnam home.

As a Vietnamese American, UCI assistant professor of global and international studies

Long T. Bui grew up learning about his family’s South Vietnamese heritage through an American

history lens. The militaristic narrative left him with many questions about the people

– including his mother and father – who were displaced. He sought their stories through

interviews and analytical research for his new book, Returns of War: South Vietnam and the Price of Refugee Memory. Below, Bui discusses the importance of recording the experiences of those who fled

a nation no longer recognized, but one that’s still very much alive in the memories

of the refugees who once called South Vietnam home.

What drew you to study what you call the “dispersed stateless exiles” of South Vietnam?

When I entered UCI as a first-year student decades ago, I knew nothing of the Vietnam War other than it was about fighting communism. There was no sense of imperialism, colonialism, or racism/sexism. Maybe because of trauma or the need for economic survival, my parents never discussed why or how they came to the United States. Exiles like them who came here had lost their country, and my uncle who served in South Vietnam’s military still sees himself as “stateless” (though not in a legal sense) because of its demise. My study emerged from the fact that when we talk about Vietnamese Americans or “overseas” Vietnamese, we are mostly talking about South Vietnamese people. While some might see it as defunct, many still view South Vietnam as alive with a viable future. This is why I explored its manifestation in everyday spaces and experiences today.

As a first-gen student now turned into a first-gen faculty, I felt disappointed that in school, I only learned and had ever known the U.S. side of things concerning the Vietnam War, which never included the Vietnamese American perspective. California Senate Bill 895 introduced by Janet Nguyen promises to change all that by teaching about Vietnamese, Hmong, and Cambodian refugees in K-12 – and that’s very exciting to hear. I actually attended four different high schools - one in Texas and three in Orange County (Fullerton, Stanton, Loara) – and none of them taught the Vietnam War that gave the “other side.” War was a military struggle and not a personal one and this is why we need more community stories.

Localize this story to Orange County, California. How many South Vietnamese refugees – and Vietnamese Americans - are living in the area and how does this compare to the rest of the U.S.?

Orange County has the largest number of Vietnamese people outside the country of Vietnam. In the OC, Vietnamese are the biggest by far of any Asian American group. In short, it is the epicenter of the Vietnamese American experience - similar to Miami for Cubans or New York or Long Beach for Cambodians. Growing up here as a teenager and young adult, I was always aware of community politics since Westminster - where “Little Saigon” is located - stands out as the place where former South Vietnamese leaders and celebrities settled. Other places like Houston, where I spent my children, have many Viets, but it does not compare to here, which feels like a Vietnamese Hollywood.

How does Vietnam’s complicated history impact the Vietnamese American community living in the U.S. today?

As a country that has gone through many wars - not just one - Vietnam has a historical legacy that is fractured and heterogeneous (and even communist Vietnam is ambivalent towards South Vietnamese refugees). To tell that story means getting different perspectives. My community is forever changing, but it holds onto a powerful legacy. For example, the new generation of youth might identify as Vietnamese American, but there is some residual attachment to being South Vietnamese. This is the history we inherit from our elders, and the current refugee crisis across the globe continues to remind many of us to use that history against rising nationalism and xenophobia.

What was the most shocking thing you learned over the course of your interviews, analysis and archival research?

Since I did multiple case studies, I found a number of somewhat shocking things. Like when a Vietnam War archive had to officially label documents under donors’ derogatory terms like “gook” or when one Vietnamese American veteran said winning in Iraq was a way to begin taking back Vietnam from communist rule. Another was the ways expats would compare Little Saigon in OC to the Big Saigon in present-day Vietnam (what is officially called Ho Chi Minh City). All these things show me there is no neat divide between past or present (future), no clear separation between here or there. The local Vietnamese American experience is also always a global one.

-Heather Ashbach, UCI School of Social Sciences

-----

Would you like to get more involved with the social sciences? Email us at communications@socsci.uci.edu to connect.

Share on:

Related News Items

- Careet RightFirst-rate advice for first-year and first-generation Anteaters

- Careet RightNa'puti receives funding for Indigenous research and connections with the canoe at UCI

- Careet RightReimagining resilient agri-food supply chains

- Careet RightDedicated to student success

- Careet RightFostering a global perspective