CHAPTER 1

THE LEGACY OF GERMAN HISTORY

| Learning Objectives:

What is Germany's Sonderweg in its socio-economic development, and what were the consequences?

Why did the Weimar Republic fail?

Was Hitler and the Third Reich an inevitable result of the Sonderweg, or an aberration of history that could have been avoided?

Why did the German public not rise up to oppose Hitler's extremist policies?

What are the differences between Germany's democratic transitions in 1945 and 1989??

|

Go to Second Empire

Go to Weimar Republic

Go to Hitler and Third Reich

Go to Reconstructing Germany

Go to Postwar Division

Go to Overview of German Unification

Go to Key Terms

Go to Suggested Readings

Go to Index of Chapters

| Quote of Note:

"The main thing is to make history,

not to write it."

Otto von Bismarck

|

Let's start with a word association game, so I can show how I can predict your thoughts.

Quick: When you hear the word "Germany," what do you think of?

If you are like two-thirds of the students who have taken my class over the years,

you did not think of the Berlin Wall, Goethe, Beethoven, German automobiles (or beer), or even German celebrities such as Heidi Klum, Michael Schumacher or even Albert Einstein.

Instead, you probably thought of "Hitler", "The Third Reich" or "the Nazis".

To be frank, this is the special stigma of German history.

The lessons of German political history are drawn in very stark terms.

Germany is the site of some of the highest and lowest points in the history of mankind. And most people remember the lowpoints.

To some extent, the politics of every nation is shaped by its historical experiences.

This especially holds true for German politics.

Germans often display an intense conviction

about their nation's "place" in history, and frequently use historical precedents to judge current political problems.

In addition, the German historical experience differs substantially from those of most other West European democracies.

The social and political forces that modernized the

rest of Europe came much later in Germany and had a less certain effect.

For some time after most national borders were relatively well defined, Germany was still split into dozens of political units.

A dominant national culture had evolved in most other European states, but Germany was torn by the Reformation and continuing conflicts

between Catholics and Protestants.

Sharp regional and economic divisions also polarized society.

Industrialization generally prompted social and political modernization in

Europe, but German industrialization came late and did not overturn the old feudal and aristocratic order.

German history thus represents a difficult and protracted process of nation-building.

Some historians argue that these experiences led Germany on a "special path" (Sonderweg) of incomplete social and political

modernization that destined the nation to follow an authoritarian course.

The evidence supporting the Sonderweg thesis comes from Germany's subsequent

political history. Once national unification was eventually achieved, the new German state followed

a course that limited political development and perpetuated the traditional feudal order.

After national unification in 1871, Germany was ruled by an autocratic Kaiser and his autocratic government.

In international affairs, German policies directly contributed to the outbreak of World War I.

The horrors of World War I shocked the world, but were soon outdone by the fanaticism of Adolf Hitler and the Third Reich.

Hitler's regime combined political oppression at home with aggressive international adventurism.

The culmination was World War II which overshadowed WWI in its death and destruction.

Germany's political legacy during the last century thus contains many negative lessons.

Indeed, because of their importance, the questions derived from the German historical

experience have been a central concern of social scientists throughout the world for nearly half a century.

This inquiry became known as the "German Question":

First, how could the failures of the democratic Weimar Republic be explained?

Second, could there be any possible explanation for the horrors of the Third Reich?

And finally, could the new, postwar Federal Republic of Germany rise above the historical legacy it inherited?

To answer these questions we need to look more closely at the historical record.

The Formation of the Second German Empire

In the mid-1800s the future German state was a collection of dozens of separate political units.

In the north, Prussia controlled an area that ranged from West of the Rhine river to the east coast of the Baltic sea.

In the south, Vienna was the center of the Hapsburg Empire, which included the multinational region of the Danube valley.

Between and within these two nations were numerous smaller states:

kingdoms, duchies, city states, and principalities. These political entities were united by

a common language, cultural tradition, and history, but they also jealously guarded their political independence.

In the 1830s and 1840s the social forces of industrialization first came into play.

The growth of an industrial sector created a new class of business owners and managers,

the bourgeoisie, who pressed for the modernization of society and an extension of political rights.

In comparison to the rest of Europe, however, the German bourgeoisie had less political influence.

Industrialization came to Germany after most of the rest of northwestern Europe.

This delay in industrialization retarded the development of many factors normally identified with a modern society: urbanization,

literacy, extensive communication and transportation networks, and an industrial infrastructure.

More important, German industrialization followed a different course than the rest of Europe because it

was integrated into the old feudal political structure.

The landed aristocracy and old elites controled economic and political development,

which lessened the influence of the new industrial class.

As a result of this developmental pattern, the democratic tide that swept across

Europe in 1848-1849 did not pose a serious threat to the political establishment in

Prussia or most other German principalities. A series of small revolutionary actions

occurred throughout Germany, and a popular assembly of representatives met in Frankfurt (the Frankfurt Assembly) to

debate proposals for constitutional reform and national unification.

This group of middle-class reformers lacked the revolutionary zeal and influence that was necessary to change the political system.

Moreover, they suffered from a problem that would weaken democratic forces in Germany for the next century.

Military conflict between Prussia and Denmark split the Assembly delegates along nationalist

lines and undercut attempts to develop a consensus on political reforms.

While the assembly bickered, Kaiser Friedrich Wilhelm IV reestablished his control over the Prussian

government and a conservative backlash developed in Vienna and Berlin.

The Prussian government functioned by the motto "Gegen Demokraten helfen nur Soldaten"

(only soldiers are helpful against democrats).

When the Frankfurt Assembly finally offered the crown of emperor

(and a constitutional monarchy) to Friedrich Wilhelm, he was again secure enough to believe in the divine right of kings and refused.

Germany's first encounter with democracy had passed with little effect, and in subsequent years liberal influences would weaken further.

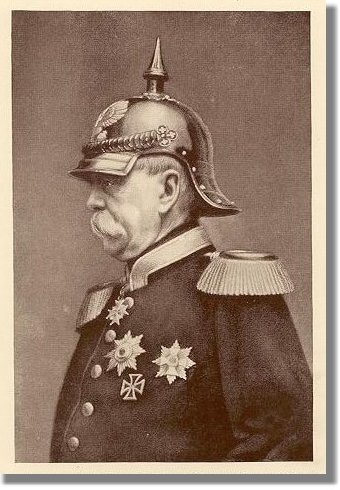

The Bismarck Era

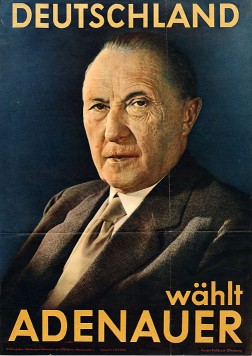

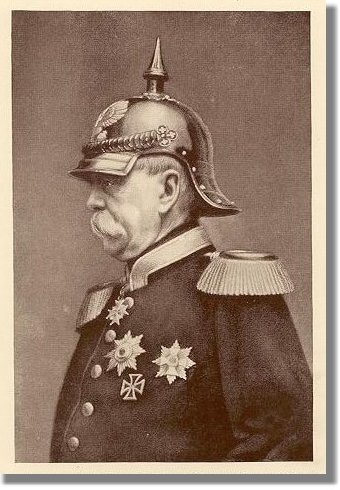

When I finally meet George Lucas, the first question I will ask is whether Otto von Bismark was

his role model for Darth Vader, because their is a close resemblence.

Otto von Bismarck became chancellor in 1862 and changed the course of history.

The conditions of Bismarck's appointment as chancellor typified his career.

When the Prussian monarch faced an impasse with liberal forces in the parliament, the Kaiser appointed Bismarck to defend the autocratic government.

By manipulating the issue of German unification, he divided and defeated the liberal challenge.

Over the next decade Bismarck enlarged the territory

of Prussia in the northern half of Germany through a combination of military victories and diplomatic skill.

Finally, in 1870 Bismarck maneuvered France into declaring war on an obviously stronger German-led alliance.

Military victories and the nationalist sentiments stirred by war led to the incorporation of the southern German states into the North

German Confederation.

In 1871 a unified Second German Empire was formed, (1) and the

Prussian monarch was crowned as emperor (Kaiser).

The new empire was a federal system.

State governments were representated in the upper legislative house, the

Bundesrat, and the public was representated in the lower house, the Reichstag.

The structure of the federal system ensured that Prussia would indirectly control the

empire; this protected the status and influence of the Prussian landed

aristocracy, the Junkers.

The constitution was fairly complex in its formal checks and balances, but in practice the Kaiser and his representative, the Chancellor, exercised

the real power. Universal male suffrage existed for Reichstag elections, but

the constitution did not transfer significant political voice to the public.

However, the government's directives to its citizens were quite clear.

Citizens had three responsibilities: to pay taxes, to serve in the army, and to keep their mouths shut.

Bismarck was primarily concerned with protecting the existing political system

and extending the power of the empire.

This philosophy led to him to attack enemies of the Reich wherever they were found.

One of the first victims was the Catholic Church (Kulturkampf).

Kulturkampf

In the 1870s the Church began to oppose liberal reforms that threatened church interests.

Bismarck viewed these activities as a challenge to the authority of the state, and

reacted against the political expression of church views such as the newly formed Center party.

With the support of liberals, the government limited the Church's role in society and

then openly attacked Catholic institutions (Kulturkampf).

The government moved against Catholic schools, initiated non-religious civil marriage, and expelled all priests

from government positions.

The infamous May laws attempted to control the appointment of new priests and expel non-cooperative members of the clergy.

By 1876 all of the Catholic bishops in Prussia were imprisoned or expelled, and a third of the Catholic parishes in Prussia lacked a pastor.

After facing resistance from the Church and its supporters in Germany, Bismarck gradually relented.

By 1887, with many anti-Catholic laws repealed, Pope Leo XIII declared the conflict over. |

Bismarck's next target was the growing working class movement.

When a new Social Democratic Party (SPD) began to win a few seats in the

Reichstag, Bismarck perceived another dire threat to the state.

In 1878 the government passed antisocialist laws, banning all meetings and publications by social democrats,

socialists, or communists. (2)

The government imprisoned or exiled hundreds of political activists over the next twelve years.

The formal institutions of the SPD were destroyed and the socialist movement was forced underground.

Bismarck used these actions to hold back the forces of political change in a rapidly developing society.

In the end, however, even he could not prevent all change from occurring.

The Kulturkampf lasted for only a few years; within a decade most anti-Church legislation ended and the

Catholic Center party became a large and fairly stable element in the Reichstag.

The suppression of the Social Democrats initially

weakened the working class movement, but it also created a stronger bond among the remaining members of the movement.

When the anti-socialist legislation was softened under Kaiser Wilhelm, the SPD's vote totals began to grow.

Furthermore, these attacks on the political opposition alienated a large segment of society and weakened

citizen identification with the political system.

How could Catholics and members of the working class identify with the new empire when they were treated as enemies of the state?

Neither the Center party nor Social Democrats represented an immediate threat to the social and political order of the empire.

Rather, they represented dissent and potential change--neither of which was tolerated by government leaders.

In overall terms, the empire's formation marked the weakening

of German liberalism and the growth of conservative and reactionary political forces.

The chancellor strengthened the conservatives in the Reichstag, and shifted the government's basis of

parliamentary support away from the national liberals who had played a significant role in the creation of the empire.

In addition, the state established a new economic order that united capitalism and the traditional aristocracy.

The government protected the Junker's agricultural interests with high trade tariffs.

Other laws catered to the demands of the new conservative industrial elites.

Wilhelmine Politics

When Wilhelm II became Kaiser, a new era began--Germany without Bismarck.

Bismarck left office in 1890, and his successors lacked the Iron Chancellor's political insights and

pragmatic skills in balancing contending forces.

While economic conditions dramatically improved beginning in 1895, the slow spiral of social and political decay continued.

The government's reliance on conservative and reactionary support in the Reichstag further alienated large segments of society.

Following the 1910 election the SPD was the largest party in the parliament, and tensions between the conservative government and

social/liberal opposition worsened.

The German sociologist, Max Weber, described the dilemma Germany faced: rule by the Junkers was undesirable, the liberal

middle class was politically inept, and the socialists were immature.

Internationally, the conditions were even worse.

One of Bismarck's major accomplishments was the protection of Germany's foreign policy interests through a

delicate balancing of international alignments.

Under Bismarck, Germany was a major force for stability and peace in Europe.

The country's international status suffered a steady decline without the master statesman at the helm.

Political leaders fed the public a steady stream of expansionist dreams, advocating a policy of Weltpolitik intended to make

Germany a world power. (3)

Instead, an ill-conceived foreign policy succeeded in alienating almost all of Europe.

In the background, the military kept pushing the country toward war with a xenophobic view of other nations and optimistic war plans.

The political system was out of control; the nation seemed to face the sobering choice of civil war or international conflict.

The assassination of Austrian Archduke Ferdinand in June 1914 was the match that sparked the tinderbox of European politics.

Germany gave Austria a "blank check" of support in its conflict with Serbia, French hostility fanned the flames of war, and the Russian army went

to full mobilization status.

A complex chain of events culminated in the German invasion of Belgium and France and the start of the First World War (1914-1918).

The conflict aroused feelings of nationalism among all the participants.

Government propaganda led the German public to view the war as an act of national defense, while also providing a

opportunity for Germany to establish its hegemony in Europe.

By encouraging these feelings, the government raised public expectations even higher.

Optimistic predictions of early victory and territorial expansion soon became mired

in the fields of Flanders, as German and allied troops confronted each other in bloody trench warfare.

At home, the war effort took a growing toll in shortages of supplies, manpower, and even food.

Over 700,000 Germans died of starvation in the winter of 1916-1917, and the war continued for nearly two more years.

As the government's legitimacy eroded, the military exercised greater control over the course of the war.

The unrealistic (and imperialistic) attitudes of generals such as Erich Ludendorff and Paul von

Hindenburg sabotaged possibilities for an early peace agreement.

Germany was not prepared for a long war on a such a scale.

The costs of war devastated the nation.

Almost three million German soldiers and

civilians lost their lives, the economy was strained beyond the breaking point, and the

government collapsed under the weight of its own incapacity to govern.

In late 1918 the generals called for an armistice to avoid the complete collapse of the nation;

two weeks later the Kaiser abdicated his throne.

The SPD majority in parliament, which had only grudgingly supported the war, faced the task of making peace

and guiding the postwar reconstruction of the society and political system.

V.R. Berghahn notes that the transfer of power from the Kaiser to parliament was not based on altruistic

motives: (4)

"After years of military-dominated government, it was now for the civilian

politicians ... to sign the armistice and hence shoulder the burden of defeat.

Even in the hour of bankruptcy, the generals showed a remarkable ability to uphold the self-interest of the Prussian military state.

As Ludendorff put it at the meeting of 29 September, as many people as possible were to be held responsible for the humiliation of defeat -- with

the exception of those who had been instrumental first in unleashing war and then in conducting it uncompromisingly."

In short, having led Germany into a catastrophic war, the military and

the empire's political establishment were eager to escape responsibility and yield power to the Reichstag.

The Second Empire left behind a questionable legacy.

Industrialization changed the economic and social system, but it did not produce political reform and modernization.

The Prussian Junkers retained their positions of influence, even after the fall of the empire.

The growth of industry also followed a distinctly German pattern.

Control of industry was concentrated in the hands of a relatively few institutions,

and individual firms were further organized into cartels which limited free trade and slowed the development of economic liberalism.

Together, the aristocracy and conservative industrial elite allied to preserve their positions of

privilege and limit the democratization of Germany. The new political order was integrated with the old.

The political system of the empire also failed to modernize.

Democratic reforms were successfully thwarted by an authoritarian state strong enough to resist the political

demands of a weak middle class.

The state was considered supreme; its needs took precedence over those of individuals and society.

Politics was marked by an intolerance of potential opposition, seen most clearly in the government's attacks on Catholics and Socialists.

Society also displayed this intolerance in periodic surges of anti-Semitic feelings.

Germans were taught to be good subjects of the state, but not participants in the

political process--especially if they disagreed with the government.

The public itself held divided political loyalties, and these differences were exacerbated by the intolerance of the political process.

In short, the empire had united Germany in geographic terms and built a strong economy, but it did not build a nation of shared political values.

According to Ralf Dahrendorf, what emerged from the Industrial Revolution in Germany was an "industrial feudal society." (5)

Modernization and democratization were still to come.

The Weimar Republic

In 1919 a popularly elected constitutional assembly established the new democratic system

of the Weimar Republic.

The constitution created a parliamentary democracy, based on a directly-elected

Reichstag and a Reichsrat of state government representatives.

The new system tried to address some of the structural problems of the Second Empire.

It constitutionally guaranteed basic citizen rights, granted universal suffrage (including women for the first time), gave

more power to the Reichstag, and lessened the political influence of the state governments.

Political parties organized across a wide range of political interests, and became legitimate actors in the political process.

Belatedly, the Germans had their first real exposure to democracy.

The constitution, however, also contained provisions that ultimately weakened the Weimar government.

A popularly elected President was to serve as a national representative, but the office evolved into a substitute for the Kaiser

(ersatz-Kaiser) during the later stages of the Republic.

The electoral procedures of referendums and proportional representation were significant democratic innovations, but

they eventually put heavy strains on a political system that lacked a popular consensus.

The federal system of Weimar also failed to solved the continuing problems of reconciling differences between the state and national governments.

And finally, the constitution included a provision, Article 48, that granted "emergency" powers to the government;

powers that were greatly abused during the later years of the Republic.

Many historians believe that the structural features of the Weimar constitution contributed to the problems

the political system eventually faced.

From the outset, severe problems plagued the Weimar government.

The most persistent difficulties involved the consequences of the First World War.

Many Germans did not believe that their country had lost the war.

The armistice was signed while German troops were still occupying French and Belgian territory, and the armies

were welcomed home as unconquered heroes.

The Versailles peace treaty thus came

as a shock to many people.

Germany lost all of its overseas colonies and a substantial

amount of European territory including Alsace-Lorraine in the West, and parts of Prussia in the East.

There was a forced demilitarization of Germany, with severe limits on the size and type of German military forces.

Finally, Germany faced very large reparation payments to pay the war-related expenses of the victorious allied powers.

Conservative politicians exploited popular dislie for the treaty and created the myth that Germany had been "stabbed in the back."

These politicians maintained that the nation's defeat and subsequent emasculation did not come from losses on the battlefield, but from

the betrayal of those groups who revolted against the empire, forced the armistice upon

the military, and founded the Weimar Republic: socialists, liberals, democrats, and Jews.

The elite class of the old empire posed another challenge.

The constitution guaranteed the status of the civil servants who had worked under the empire,

which ensured the presence of many government officials who opposed Weimar's democratic system.

Many judges blatantly gave preferential treatment to right-wing

radicals who attacked the Weimar government, while dealing harshly with leftists.

Universities often became centers of anti-democratic thought.

In responding to a series of radical uprisings, the military showed that it would defend the Republic from leftist

attacks, but not necessarily against conservative or reactionary forces that wished to restore the empire.

The early years of the Weimar Republic were ones of perpetual political instability.

In 1919 there were radical uprisings from both left and right extremists.

The following year the Kapp Putsch attempted to overthrow the government.

Government officials reacted to the Versailles treaty with self-defeating exhibitions of defiance,

and Germany's international position deteriorated.

Resistance to the allies' reparation plans led to France's occupation of the Ruhr in January 1923, which further incited extremists

and destabilized the political system.

These political problems worsened the already ill economic health of the nation. (6)

The Kaiser had financed Germany's actions in World War I through loans rather than increased taxes.

Gradually the burden of these loans, the weakness of the economy, the

pressure of reparation payments, and the consequences of France's occupation of the Ruhr eroded confidence in the economy.

Total industrial production in 1923 was only 55 percent of the prewar level.

Government printing presses kept the nation afloat on a sea of inflated currency and a brewing inflation problem finally exploded in 1923.

In less than a year the inflation rate was an unimaginable 26 billion percent.

Yes, billion with a "b".

German currency became worthless.

For example, a kilogram of potatoes that cost 20 marks in January carried a price tag of 90 billion marks by October. (7)

A single Berlin street car ticket that already was 100 thousand marks in August cost 150 million marks in November.

Some workers were paid twice a day, and then given time off from work to rush out and spend their money before the daily price rates were revised.

Many small self-employed business people were forced out of work.

Families that had saved for a retirement saw their life savings become worthless overnight; bonds and savings accounts

had virtually no value.

Those who were already retired on a fixed income often became wards of the state.

The middle class suffered economic hardships even greater than the experiences of World War I.

This hyperinflation contributed to a general process of social

disintegration, rising crime rates, and a disillusionment with the political system.

Units within the army planned coups against the government; signs of imminent leftist revolts also surfaced.

A little known radical, Adolf Hitler, attempted to mobilize nationalist forces

in Bavaria into a Putsch against the government.

This time Hitler failed and was sentenced to a short prison term, and he wrote his political philosophy, Mein Kampf, during this year.

In the end, the government was able to resist these attacks and stabilize prices before the end of the year.

Still, the severe economic losses of the middle class could not be

restored and many citizens saw the inflation crisis as another example of the failures of the Weimar democracy.

Hitler's Mein Kampf available online

By the mid 1920s the political tensions that eventually tore apart the Weimar

Republic were becoming visible. The parties that had formed the Weimar Republic--

Socialists, Liberals, and the Center party--lacked cohesion and lost support at the polls (see table 1.1).

The Social Democrats would not broaden their political views beyond their

Marxist origins and thus could not work effectively with the other political parties.

The liberal parties lost influence and voting strength.

The moderate Centrist party gradually moved toward the right.

The pro-democratic parties were under attack from radicals on the left (the Communists) and the right (the nationalist parties).

Government leaders reverted to Bismarck's strategy: foreign policy initiatives distracted attention from the

government's domestic problems.

The Beginning of the End

The fatal blow to the Weimar Republic came with the Great Depression in 1929.

The nation was caught in the grasp of a worldwide economic downturn, and its already fragile economy was especially vulnerable.

Employment rates declined and business failures spread.

Nearly one sixth of the labor force was out of work by 1930, and millions more were underemployed.

These economic problems were compounded by Germany's dependence on foreign loans and investments, and the continuing drain of reparation

payments.

Moreover, as tax revenues decreased, growing demands for unemployment benefits and social assistance created increasing demands on the government's budget.

The public was frustrated by the government's inability to deal with this latest crisis.

Political tensions increased, and parliamentary democracy began to fail.

In 1930 the government of Chancellor Heinrich Brüning tried to generate political support for a program of economic

reform, but the parties in the Reichstag seemed irreconcilably divided.

Brüning dissolved the parliament and called for new elections.

In the midst of this political void, the government bypassed the parliamentary process and implemented its reforms by presidential decree.

This event marked the government's first significant break with the

democratic principles of the Weimar Republic, and opened the door to further erosion in the constitutional process.

In the crisis environment of 1930, turnout at the polls increased and many voters

succumbed to calls for radical change.

Adolf Hitler and his

National Socialist German Workers' Party (NSDAP),

Nazis, were the major beneficiaries (table 1.1).

The Nazi vote increased from a mere 2 percent in 1928 to 18 percent.

At the other extreme of the political spectrum, the Communists also improved their vote totals.

Together the anti-system parties -- Nazis, Communists, and Nationalists -- controlled nearly half of the

seats in the Reichstag and blocked any prospects for moderate policy reform.

Table 1.1 Reichstag Election Results (percentages), 1919-1933

| Party |

1919 |

1920 |

5/1924 |

12/1924 |

1928 |

1930 |

7/1932 |

11/1932 |

1933 |

| Left |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Communist |

- |

2.1 |

12.6 |

9.0 |

10.6 |

13.1 |

14.3 |

16.9 |

12.3 |

| Ind. Socialist |

7.6 |

17.9 |

0.8 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

-- |

| Socialists |

37.9 |

21.7 |

20.5 |

26.0 |

29.8 |

24.5 |

21.6 |

20.4 |

18.3 |

| Center |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Zentrum (Z) |

19.7 |

13.6 |

13.4 |

13.6 |

12.1 |

11.8 |

12.5 |

11.9 |

11.3 |

| Liberals |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| German Dem |

18.6 |

8.3 |

5.7 |

6.3 |

4.9 |

3.8 |

1.0 |

0.9 |

0.8 |

| Peoples Party |

4.4 |

13.9 |

9.2 |

10.1 |

8.7 |

4.5 |

1.2 |

1.9 |

1.1 |

| Nationalists |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Nationals |

10.3 |

15.1 |

19.5 |

20.5 |

14.2 |

7.0 |

5.9 |

8.3 |

8.0 |

| Nazis |

- |

- |

6.5 |

3.0 |

2.6 |

18.3 |

37.3 |

33.1 |

43.9 |

| Other |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Other parties |

1.6 |

7.4 |

11.8 |

11.5 |

17.1 |

17.0 |

6.2 |

6.5 |

4.3 |

| TOTAL VOTE |

100% |

100% |

100% |

100% |

100% |

100% |

100% |

100% |

100% |

| Turnout |

82.7 |

79.2 |

77.4 |

78.8 |

75.5 |

82.0 |

84.0 |

80.6 |

86.7 |

The economic situation continued to deteriorate in

1931 and 1932.

During the worst periods of 1932 nearly one out of every three workers was unemployed; the unemployment rolls swelled to over 6 million people.

Political violence and street battles between rival political groups threatened the social order.

The presidential election in 1932 reflected the nation's darkening mood.

President Paul von Hindenburg, the former World War I general, and Adolf Hitler faced each other in a runoff election for the Federal Presidency.

Hindenburg grudgingly tolerated the democratic process and Hitler was dedicated to its overthrow.

Just the choice of final candidates signaled the vulnerability of

the Weimar Republic, and Hitler's strong second place finish represented an ominous sign of the future.

In subsequent state elections the Nazi vote continued to pick up momentum.

People were looking for radical solutions to their worsening situation.

The economic situation continued to deteriorate in

1931 and 1932.

During the worst periods of 1932 nearly one out of every three workers was unemployed; the unemployment rolls swelled to over 6 million people.

Political violence and street battles between rival political groups threatened the social order.

The presidential election in 1932 reflected the nation's darkening mood.

President Paul von Hindenburg, the former World War I general, and Adolf Hitler faced each other in a runoff election for the Federal Presidency.

Hindenburg grudgingly tolerated the democratic process and Hitler was dedicated to its overthrow.

Just the choice of final candidates signaled the vulnerability of

the Weimar Republic, and Hitler's strong second place finish represented an ominous sign of the future.

In subsequent state elections the Nazi vote continued to pick up momentum.

People were looking for radical solutions to their worsening situation.

To maintain some semblance of political order, the Brüning government turned

further and further away from the democratic process, ruling by presidential decree and

relying on the emergency powers of Article 48.

Nevertheless, conservative leaders in industry, government, and the military felt that the government was still too democratic,

and this limited its ability to take the strong measures they felt were necessary to solve the nation's economic and political problems.

Many of these elites favored restoration of an authoritarian state, and began working toward that goal.

In May of 1932 Brüning was forced from the chancellorship by von Hindenburg; Franz von Papen and a nationalist cabinet took control.

Von Papen was a nobleman and a former military officer; he was also a monarchist who wanted to restore the empire of the Kaiser.

The historian, Hajo Holborn, maintains that "with Brüning's resignation, democracy in Germany ... was dead." (8)

Papen's government quickly moved against its democratic opponents.

At the same time, the legal bans against the Nazi paramilitary organizations, the SA and SS, were removed.

The SPD-led Prussian government was overturned by decree.

In the July federal elections the Nazis made major gains, winning 37 percent of the votes and emerging as the largest party

in the Reichstag.

When the new Reichstag opposed the government's program, another round of elections were planned for November.

These were the last free elections of the Weimar democracy.

Although the Nazis lost votes in the election, the parliament was still deadlocked.

Political violence was increasing, and the country again seemed on the verge of civil war.

In a final attempt to restore political order, President Hindenburg appointed Hitler chancellor of the Weimar Republic in January 1933.

The collapse of the Weimar democracy was complete.

Why Weimar Failed

Weimar's failure opened the door to a Nazi regime that would corrupt Germany and begin

a world-wide conflagration.

Thus, social scientists have invested a great effort to understand what led to Weimar's demise.(9)

There is no single explanation.

Rather, Weimar's collapse resulted from an interaction among a complex set of factors.

A basic weakness of the Weimar Republic was its lack of support from political elites and the general public.

From its birth, the Republic lacked a popular

consensus behind the democratic institutions and procedures of the new political system.

The elite class of the Empire retained control of the military, the judiciary, and the civil service.

Democracy depended on an administrative elite that often longed for a return to

a more traditional political order. Gordon Craig maintains that: (10)

"The Republic's basic vulnerability was rooted in the circumstances of its

creation, and it is no exaggeration to say that it failed in the end partly

because German officers were allowed to put their epaulets back on again

so quickly and because the public buildings were not burned down, along

with the bureaucrats who inhabited them."

Many political leaders also opposed the Weimar system.

Even before the onset of the Depression, many influential political figures were working for the overthrow the Weimar system.

These anti-republican forces gained strength when the economy

faltered, and what was worse, the Nazis eventually established themselves as the vanguard of the anti-democratic movement.

Elite criticism of Weimar was shared by many average citizens and

encouraged by the rhetoric of elites. Many people felt that the creation of the Republic at

the end of World War I contributed to Germany's wartime defeat; from the outset the

regime was stigmatized as a traitor to the nation.

Large portions of the public retained political ties to the Second Empire, and questioned the legitimacy of the Weimar Republic.

Germans still had not developed a common political identity, a political culture, that could unite and guide the nation.

The fledgling democratic state then faced a series of major crises: repeated leftist

and rightist coup attempts, political assassinations and violence, the inflation of the 1920s and the Depression of the 1930s.

Such strains might have overloaded the ability of any system to govern effectively.

The political system was never able to create a reservoir of popular support that

could sustain it through these crises. Consequently, the dissatisfaction created by the Great

Depression dangerously eroded public confidence in the political system.

Nazis, Nationalists, and Communists argued that the democratic political system was at fault, and

many more Germans lost faith in the Republic. Even the actions of the so-called Weimar

parties (Socialists, Liberals, and the Center) contributed to the undemocratic mentality of

the times. Party leaders too often placed ideological purity and partisan self-interest above

the national interest. Politicians were hesitant to negotiate and compromise, and frequently

displayed an intolerance of divergent points of view. These attitudes led to a fragmentation

and radicalization of the party system. Instead of showing the public how "good"

democrats should act, politicians often furnished negative role models. As the situation

worsened, the leadership of several moderate and conservative parties displayed more

concern in protecting the power and authority of the state than in protecting democracy.

In many senses, Weimar was weakened by the legacies of intolerance and weak democratic

values that it inherited from the authoritarian system of the empire.

The political institutions of Weimar also contributed to its vulnerability.

Political authority was not clearly divided between parliament and the president.

The infamous Article 48 granted the president broad emergency powers to protect the constitution that

eventually were instrumental in the overthrow of democracy.

As the government's reliance on emergency decrees expanded (from 5 in 1930 to 57 in 1932).

This eroded the basis of parliamentary democracy.

The decrees forced a series of unpopular policies upon the public: reducing wages and social services, while increasing taxes.

Moreover, the decrees did not solve the economic problems of the Depression but they did stimulate opposition to the government,

and the Nazis led the assault.

Finally, most Germans drastically underestimated Hitler's ambitions, intentions,

and political abilities. Industrial leaders discounted his policies as political rhetoric, and

eventually supported him in exchange for promises of political and economic stability.

Political moderates who read Hitler's writings and listened to his speeches still convinced

themselves that his anti-Semitism and excessive nationalism only existed for political show.

Even at the end of Weimar, conservative politicians thought he could be controlled as

chancellor by the nationalist parties in his cabinet. Everyone, it seems, tried to ignore the

true nature of Hitler and his policies. This, perhaps, was Weimar's greatest failure.

Hitler and the Third Reich

The Nazis' rise to power was incredibly quick.

Hitler first announced the formation of the NSDAP in 1920 and 13 years later he was chancellor.

Admittedly, the party's fortunes had fluctuated uncertainly.

After the abortive coup in 1923 the party attracted little public attention for several years.

The Nazis' phenomenal growth in voting support in the early 1930s led to their rise to power.

To understand the origins of the Third Reich we need to understand why Hitler's party appealed to so many voters.

The Nazis' rise to power was incredibly quick.

Hitler first announced the formation of the NSDAP in 1920 and 13 years later he was chancellor.

Admittedly, the party's fortunes had fluctuated uncertainly.

After the abortive coup in 1923 the party attracted little public attention for several years.

The Nazis' phenomenal growth in voting support in the early 1930s led to their rise to power.

To understand the origins of the Third Reich we need to understand why Hitler's party appealed to so many voters.

There was never any question that Hitler was a demagogue.

He preached anti-Semitism and theories of racial superiority, he advocated the destruction of

democracy and the construction of a Nazi dictatorship, he championed ultra-nationalist policies that could only lead to war.

These views were clearly spelled out in his book, Mein Kampf, and in innumerable Nazi publications.

How could so many Germans vote for such a man?

A large part of the NSDAP's success can be

traced to the creation of a new political model that overwhelmed its opponents when crisis befell the Weimar Republic.

One hallmark of the NSDAP was its organizational efficiency.

The central party office commanded an extensive network of closely coordinated regional and local branches.

On any given day the party headquarters could direct an impressive nation-wide propaganda

campaign that was faithfully repeated in almost every German regions and city.

Another feature of the party was its paramilitary units, the SA and SS. These units furnished a

military air at political rallies, and intimidated the party's opponents through acts of violence.

During election campaigns the NSDAP could produce more leaflets, amass more

supporters at rallies, out battle its opponents in street fights, and out campaign most other parties.

Another source of the Nazi appeal was their

unprincipled propagandizing.

Hitler was a charismatic leader and a dynamic speaker who could play on his audience's emotions.

The party rallies were elaborately staged to create a mood that Hitler exploited.

Martial music and rousing speeches combined with mass marches and military drills to stir the participants into a

emotional fever--culminated by Hitler's dramatic arrival and demagogic oratory.

Such propaganda shows were an important component of the Nazi movement, but the appeal of the NSDAP went deeper.

Another source of the Nazi appeal was their

unprincipled propagandizing.

Hitler was a charismatic leader and a dynamic speaker who could play on his audience's emotions.

The party rallies were elaborately staged to create a mood that Hitler exploited.

Martial music and rousing speeches combined with mass marches and military drills to stir the participants into a

emotional fever--culminated by Hitler's dramatic arrival and demagogic oratory.

Such propaganda shows were an important component of the Nazi movement, but the appeal of the NSDAP went deeper.

Popular support for the NSDAP came from the

party's attempt to transcend traditional social divisions and develop into a party of national integration.

Rather than just appealing to farmers, or workers, or one religious group, the party tried to attract support

from all sectors of society.

One source of this broad appeal was a vehement nationalistic policy.

The Nazis nurtured the "stab in the back" myth, and attacked the conditions of the

Versailles treaty as an unjust international conspiracy against Germany.

The party argued that Germany was being deprived of its rightful role in the world, and the public proved

all too receptive to such nationalistic sloganeering.

The party also developed electoral campaigns targeted to different social groups

based on a two-pronged tactic of lofty promises and accusations against the group's purported enemies.

To the middle class of small farmers and merchants the party promised

government aid at the same time that it attacked the supposed enemies of the German

middle class: Jewish financiers and the Marxist welfare state.

The Nazis appealed to blue collar workers by promising full employment and the true socialism of a united Volk, while

attacking capitalism and Marxism as the oppressors of the working class.

Pensioners were told that the government's cuts in retirement benefits were unnecessary, and only the

Nazis could rescue them from destitution.

In short, Hitler sought to be all things to all people.

Contemporary voting research finds that people generally vote "against" the

failures of the government, rather than "for" the program of the opposition.

Clearly, Weimar had many failures, and the Nazis were the loudest non-Marxist critics of the Weimar system.

At the depth of the Depression the German people were desperate, and many succumbed to the Nazis' impossible promises.

They overlooked the contradictions and extremism of the Nazi program and focused on their own insecurities.

The core of Nazi support came from three areas: non-Catholic rural districts, the upper class, and the

petite bourgeoisie.(11)

At the same time, a significant share of the Nazi vote came from conservative members of the working class and lower middle class.

A study of NSDAP members testified to the diversity of the party's appeal: 34.4 percent of the members who

joined before mid-1930s came from the self-employed middle class, 28.1 percent were

from the working class, and 25.6 percent were salaried white collar employees. (12)

The Nazis were a socially diverse party of antis--anti-democracy, anti-Versailles, anti-capitalist,

anti-Jewish, or anti-Marxist--but it is unclear whether these same voters agreed on Nazism as the alternative.

Taking Control

Once Hitler gained the chancellorship, he began to consolidate his political power.

Against the wishes of the other parties, Hitler called for new Reichstag elections in March 1933.

The elections occurred under a shadow of Nazi threats and violence.

Hitler used a presidential decree to suppress the Communist party and severely restrict the campaigning of the SPD.

The Nazis' control of the Prussian police enabled the SA to attack political opponents with official sanction.

The state-run radio was turned to Hitler's use.

Public expression of opposition was reduced to a minimum.

Even in the oppressive environment of the elections, the Nazis failed to win a

majority of the popular vote.

Many people still resisted Hitler's appeal.

Nevertheless, NSDAP gains in the election led to the collapse of opposition to Hitler by most political elites.

With the support of the other nationalist parties Hitler moved to revise the constitution and end the democratic era of the Weimar Republic.

The Reichstag met on March 23rd. The newly elected Communist party deputies were excluded, and several

SPD deputies were prevented from attending by the ring of Nazi stormtroopers surrounding the parliament.

The other political parties had already come to terms with

Hitler. Only the SPD opposed the Enabling Act which granted Hitler dictatorial powers.

Weimar was replaced by the Third Reich, and the black-red-gold flag of democratic

Germany was replaced by the swastika on the black-red-white colors of imperial Germany.

Hitler then moved to create the new National Socialist order. The Nazis destroyed

all potential bases of internal opposition through a process of "coordination"

(Gleichschaltung). Social and political groups that might challenge the government were

destroyed, taken over by Nazi representatives, or coopted into accepting the Nazi regime.

Learning from the lesson of Weimar, Hitler moved against the civil service within a month of coming to power.

Officials who were sympathetic to democracy or the SPD were

removed from government service, along with civil servants of Jewish descent.

Nearly a third of the civil servants in Prussia, for example, were purged in this manner. As a result,

Hitler assured that the remaining government officials would obey Nazi directives.

Socio-economic groups were the next targets of "coordination." To assure the

working class of the Nazis' good intentions, May 1st was declared a national workers' holiday.

On May 2nd the Nazi SA troops broke into labor union headquarters and forcibly

took control of the union movement. Within a few weeks the Nazis had created a new

labor organization in the National Socialist image. Next in line were the farmers. Hitler's

representative gained control of the leading agricultural association, and then became

agricultural minister in the Nazi government. The various small businesses associations

suffered a similar fate over the next several months. The only significant economic interest

group to resist the Nazis domination was the Federation of German Industry. Hitler did

not have to control industry by force, he only had to guarantee enough profits to buy their support.

The political parties faced escalating pressure as soon as the Nazis first assumed power.

The SPD was divided on how to deal with the NSDAP. Some SPD leaders favored

opposition from exile, while other party leaders wanted to oppose the Nazis within the legal channels of the Third Reich.

Hitler resolved this quandary by outlawing the SPD in June 1933 and imprisoning many of the remaining SPD leaders in Germany.

Once the largest partisan challenge was removed, the other parties provided little resistance to the Nazi onslaught.

Over the next few weeks the German People's party, Bavarian People's party, and former Democratic party quietly dissolved.

When the Vatican reached a concordat assuring the rights of the Catholic Church in Nazi Germany, the

Center party also disbanded.(13)

On July 14 the government declared that the NSDAP was the only legal party acknowledged by the Third Reich and party

competition came to an end.

The Nazi coordination drive moved with such speed that most potential sources

of political opposition were destroyed within the first year of the Reich.

The most significant criticisms of Hitler then came from within the ranks of the NSDAP itself.

The head of the SA troops, Ernst Röhm, pressed for a greater role within the Nazi government for himself and his troops.

Hitler's solution to this challenge was simple.

On the night of January 30, 1934 ("The night of the long knives"), Hitler's elite SS corps assassinated

Röhm, dozens of other SA leaders, and other opponents of the Reich.

The brutality of the Third Reich was clear for all who wished to see.

The Nazis' total consolidation of political power came after the death of President Hindenburg in mid-1934.

Hitler assumed the political authority and responsibilities of the office of president, and he chose a new title to signify his role in the new Germany.

Hitler became the Führer (leader) of his people as well as Reichschancellor of the government.

Hitler controlled the dual structures of the Nazi party and the Nazi state.

Führer-power (Führergewalt) became the ultimate source of political authority.

As their commander-in- chief, the armed forces had to swear their allegiance to Hitler.

With the military's formal oath of "unconditional allegiance to the Führer," the Nazis' coordination

process was essentially complete.

Just before Hitler became chancellor von Papen had predicted that Hitler would

last only a few months before being forced from office. The Nazis, after all, controlled

only two government ministries and supposedly were no match for the skillful political leaders of the

conservative parties. He predicted that after Hitler was brought under control, the

conservative parties could then create their own political revolution. These predictions,

like many more to follow, disastrously underestimated Hitler. In actual fact, within only

18 months of becoming chancellor, Hitler assumed nearly total control of society and politics.

Hitler's Domestic Policies

The Nazi state used its extensive power to restructure the economy.

It first worked to reduce the vast numbers of unemployed workers by investing in job-creation projects.

The German autobahnen were the centerpiece of a program that included public works, large housing projects, and other heavy construction.

Another aspect of the recovery program, and more important to Hitler, was Germany's rearmament.

At first secretly and then boldly violating the Versailles treaty limits on German military strength, Hitler

began a military buildup greater than any nation had ever pursued in peacetime.

The health of the economy quickly improved.

Unemployment decreased from about six million in January of 1933 to four million in 1934 and only two million in 1935.

The situation of the average worker noticeably improved because of higher employment levels

and a stable or slightly increasing standard of living.

In addition, the government's optimistic propaganda reports and diminished social strife improved the economic climate.

By 1936 full employment was achieved and industrial production surpassed the pre-Depression levels.

Hitler is generally credited with successfully restoring the German economy, even

while most Western democracies were still suffering from the Depression.

In many ways, however, it was a false success.

While the government's economic program boosted employment, the costs of this program was not as immediately obvious. (14)

The economic advances were very uneven; farmers actually suffered from Nazi agricultural policies.

The social costs of Nazi policies were often overlooked.

Women, for example, were pressured to leave the labor force and assume traditional social roles as wife and mother.(15)

Moreover, the government was spending at unsustainable levels.

Public expenditures accounted for a larger share of the national economy than in Britain or France.

The government increased taxes to finance these expenditures, but even these new revenues were inadequate.

Government debt skyrocketed, quadrupling in six years.

In the long term the government's polices would lead to economic collapse, but Hitler's plan focused on building the infrastructure for war.

By 1940 Germany must be winning a war of conquest, or the long term effects of the government's economic program would become obvious.

Germany was racing toward a precipice.

International Conquest

Hitler charted Germany's course toward war long before the actual outbreak of hostilities.

First, he insisted that Germany throw off the burden of Versailles and renounce limits on

Germany contained within the treaty. Second, he called for an expansion of German

territory to the east which would provide the living space (Lebensraum) for future

agricultural and economic growth. These two foreign policy goals guided the actions of

the Third Reich.

Hitler's style was to challenge the international status quo directly and then depend

on the inaction of other European powers or their willingness to compromise.

Regrettably, almost every one of his initial foreign policy adventures was successful, emboldening him still further.

In 1935 Hitler renounced the Versailles limits on German military forces and the allies did little.

A year later he remilitarized the Rhineland. His critics feared that this

risky policy would fail; its success weakened any remaining sense of caution. Austria was

merged into the Reich in 1938. When Germany threatened Czechoslovakia over the status

of German-speaking border areas, the British Prime Minister responded by offering the

territory to Hitler. In March of 1939 German troops marched into Prague. The Third

Reich was the most powerful state in Europe.

When the other European nations finally realized the true scope of the Nazi threat,

it was almost too late. Britain and France quickened the pace of their military buildup.

Meanwhile, Hitler had obtained a mutual non-aggression treaty with the Soviet Union.

This removed the threat of Germany having to fight a two front war as in World War I.

Hitler hoped that the allies would remain neutral as he moved to expand German

territory into Poland, but he was also prepared for full scale war.

On September 1, 1939 German troops invaded Poland. Britain and France came to Poland's defense and declared

war on Germany--World War II had begun.

What started as a localized conflict progressively widened as the Axis powers--

Germany, Italy, and Japan--displayed their imperialistic intentions.

German mechanized armor and dive bombers overwhelmed the Polish defenses in a few weeks.

In April of 1940 Hitler's troops occupied neutral Denmark and Norway.

Belgium and the Netherlands were invaded and defeated in May.

The army moved on to France and by mid-June the French government capitulated.

Only England remained to battle the Nazi advance in Western Europe.

The incredibly rapid pace of German victories added a new term to the vocabulary of warfare, Blitzkrieg.

The war continued to expand in 1941. The Balkans were invaded in the Spring and

quickly brought under Nazi control.

In June Hitler began his most ambitious campaign, the invasion of the Soviet Union, ignoring the non-aggression treaty he signed two years earlier.

German troops raced across Russia, but an early winter halted their advance on the outskirts of Moscow.

Japan's surprise attack on Pearl Harbor in December

brought the United States into the conflict and made the war truly worldwide in scope.

Germany had now overextended its resources and hopes for rapid victory faded.

During 1942 the allies developed air and naval superiority over German forces in Western Europe.

Allied troops in North Africa forced the Germans from the region in early 1943, followed by an Allied invasion of Italy.

In the East, the German defeat at Stalingrad in January 1943 began a long German retreat that would eventually end in Berlin.

The turning point in the war had been reached.

War is always violent and harsh, but many actions of the Nazi state in conquering

the territories in the East displayed a brutal disregard for humanity. Hitler's concept of a

German Lebensraum called for the expulsion of millions of Poles and Russians from the

eastern territories destined to be new German colonies. Poland was to become a nation of

slave laborers, with only rudimentary education and minimal living standards. As German

troops invaded Russia, special SS squads (Einsatzkommandos) murdered

over a million Soviet political activists and Jews, and terrorized the population. Millions

of foreign workers were relocated to Germany and forced into the production lines of

German factories. The Nazis considered the Slavic populations as subhumans and

virtually any actions against them appeared justified.

The inhumanity of the Nazi regime is most clearly seen in its actions toward the Jews. (16)

Germany, as many other European nations, had experienced recurring periods of

antisemitism, often associated with national crises such as the depression of 1873 and the

collapse of the empire in 1918.

The Nazis, however, made Aryan racial superiority and virulent antisemitism central themes of the party's program.

Hitler attacked the Jews as symbols of everything that was wrong with the Weimar Republic and found a receptive audience among many people.

Hitler unabashedly stated that his goal was to rid Germany and Europe of Jewish influences.

The Third Reich introduced steadily more oppressive measures.

One of Hitler's first actions in 1933 was to purge Jews from the civil service.

The Nuremberg laws in 1935 stripped citizenship rights from Jewish citizens, and strengthened the racist aspects of Nazi ideology by prohibiting intermarriage with Jews.

Outright violence and oppression of the Jews attempted to force them to emigrate.

Jews were systematically excluded from economic and social activity simply because of their religious heritage.

Kristallnacht

On the infamous Kristallnacht

1938, named for the shattered glass of Jewish-owned stores, SA troops attacked

thousands of Jewish-owned businesses and destroyed hundreds of Jewish synagogues. Dozens of Jews were killed by the mobs,

and up to 30,000 more were deported to concentration camps. The government later

confiscated the insurance payments as compensation for the disruption caused by the Jews!

The violence of Kristallnacht aroused the world to condemn the Nazi actions, and many Germans privately

opposed these activities, but were afraid to act. This mass violence was a precussor tprecursoruld follow.

|

When German war hopes began to fade, the Third Reich began a top secret

program to exterminate all Jews in German occupied territory. Dozens of concentration

camps were established throughout Europe. Jews were rounded up and sent by railway

cars to the camps. At Auschwitz, Treblinka, Bergen-Belsen and the other camps the Third

Reich brutally exterminated Jews, socialists, communists, democrats, homosexuals and others the

regime found socially undesirable. In the end, six million European Jews were murdered.

Visit the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum online

The war ended as it had begun -- with all eyes focused on Hitler.

As Soviet troops surrounded Berlin and the allies rapidly advanced through Western Germany, Hitler

directed the last final desperate defense of his Third Reich. When all hope was lost, he

committed suicide and left Germany to suffer the consequences of his leadership.

On May 8th, Germany surrendered unconditionally to the victorious Allied forces. Sixty million

lives were lost worldwide in the war. Germany lay in ruins: its industry and transportation

systems destroyed, its cities in rubble, millions left homeless, and with little food. Hitler's

grand designs for a new German Reich instead had destroyed the nation in a Wagnerian

Götterdämmerung.

Reconstructing Germany

May 8, 1945 is generally considered the "zero hour" in the development of postwar German politics.

Hitler had insisted that Germany battle until the bitter end, even after all hope of victory was lost.

Thus the cost of defeat soared much higher than in World War I.

The nation suffered massive social, economic, and political destruction.

The economy was shattered; citizens were destitute; and politics became a denigrated activity.

Germany faced a long road back to social and national recovery.

Moreover, at the war's end no one knew where that road would lead, and almost all were convinced that

it would be a very long journey.

Opinion surveys conducted more than a year after the war ended showed that many Germans in the West expected the military

occupation by the Allies to last half a century!

Military Occupation

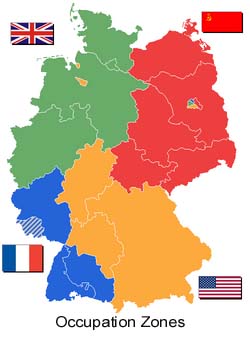

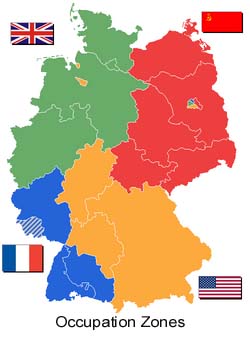

Even before the end of World War II, the Allied powers planned the fate of postwar Germany.

One of the first decisions was to divide German territory in

order to dismantle the Nazi state and simplify public administration.

Germany was to be partitioned into three occupation zones, each under the control of a separate military commander.

The United States would administer southern Germany, Great Britain the northern region, and the Soviet Union the eastern region.

Later, France joined the Allied powers and occupied a zone drawn from the American and British sectors.

The conquered German capital of Berlin, which was over a 100 kilometers within

the Soviet occupation zone, would be administered by a joint Four-Power commission.

The Allies also agreed on broad guidelines for their postwar actions

towards Germany, commonly known as the four-Ds: demilitarization, decartelization, de-nazification, and democratization.

Policies of demilitarization and denazification to immediately remove the Nazi threat held top priority.

For instance, war related industries would be seized by the occupation forces and dismantled or converted to other production.

The Allies also endorsed the principles of administrative decentralization and the breaking up of Germany's large industrial cartels.

Beyond these general goals, the views of the Allies often failed to converge.

Questions about the details of administration, economic reconstruction, and political reform remained unresolved at the war's end.

Several Allied summits failed to reach agreement on the conditions of peace and the intended structure of postwar Germany.

Even while the Allies celebrated their imminent victory, fundamental divisions existed in their political orientations.

Policy differences among the Allies arose for several reasons. Each of the Allied

governments sought different goals from the defeat of the Third Reich. (17) The Soviet Union

pressed for large reparation payments (to recover a portion of its wartime losses) and

territorial concessions to Poland (to compensate Poland for its territorial losses to the Soviet Union).

In order to lessen the possibility of another German threat on its eastern

border, France favored the dismemberment of Germany and gaining some territory from Germany.

The U.S. policy was ambiguous.

America wanted to remove Germany as a military and political threat to the world, but U.S.

policy makers were divided on how best to accomplish this.

Many foreign policy officials advocated reform and democratization of postwar Germany, in order to

avoid the popular resentment and hostility that accompanied the harsh terms of Versailles.

President Roosevelt, however, preferred to limit Germany's economic and political force once and for all.

In the Spring of 1944, Roosevelt officially adopted the Morgenthau Plan which called for returning Germany to a non-industrial, agrarian society.

Britain preferred a solution closer to the American reformist program.

The Allied governments also disagreed on the causes of

Nazism, and hence the steps necessary to remove this influence from German society.

Many French elites saw National Socialism as an extension of Prussian nationalism

and authoritarian values; they therefore favored the destruction of Prussia and eradication

of these attitudes from the German culture. The Soviets viewed the Third Reich as a

stemming from the excesses of Western capitalism; only a social revolution on the Soviet

model could correct this situation. The British saw Hitler's ascent to power as a failure of

political leadership, and consequently emphasized the removal of Nazi sympathizers from

leadership positions. American sentiments were divided between those who viewed the

Third Reich as an unique, abnormal failure of the political process and those who

considered Hitler an inevitable consequence of the German pattern of political development.

When the Allied occupation forces took control of Germany in May 1945, the

magnitude of the problems they faced temporarily overshadowed the differences amongst them.

Germany presented a gloomy picture. The casualties of war personally affected

millions of German families and virtually all personal savings had been lost with the collapse of the Nazi government.(18)

In addition, nearly a quarter of Germany's prewar

territory, encompassing all lands east of the Oder-Neisse rivers, was placed under Polish or Soviet administration.

Several million ethnic Germans were expelled from these territories and the other nations in Eastern Europe and forced to Germany.

These expellees, having left all their property to flee for their lives, settled in refugee camps and

added to the burden of postwar reconstruction.

A later wave of refugees from the communist nations of Eastern Europe swelled the number of relocated persons to over 10

million.

The German economy could not match the demands placed on it. (19)

Much of the country's productive capacity was either destroyed, idle, or being dismantled by the victors:

Industrial production in 1946 was only 33 percent of the

1936 level, and that national income reached only 40 percent of its prewar level.

The transportation system lay in ruins; railways and waterways had been blocked by Allied

bombs or by the retreating German troops.

Almost 50 percent of prewar housing units were destroyed or damaged, and the number of homeless was swelled by the expellees

from the east.

Agricultural production, especially in the more industrialized western occupation zones, could not feed this large population.

Shortages of food and basic necessities created a thriving black market, where some goods sold for 50 to 100 times

their official price.

It was estimated that even with the help of American food donations the average daily food intake over the years 1945 to 1947 was only 1300 calories per

person.

Not until December 1947 did the American military command conclude that the

German people had sufficient food to avoid malnutrition.

The Western Allies initially followed the strategy of the Morgenthau Plan.

Economic recovery preceded slowly,however.

The Allies found that the costs of sustaining the Germans were substantial,

especially if there was expropriation of the industrial resources that could restore the

economy. The Western Allies realized that the destruction of Germany's industrial base

was counter productive, since this was the only means that the Germans could use to sustain themselves.

The dismantling of German industry for reparation payments gradually ended in the western zones.

The Soviet Union aggressively broke up German industrial cartels

and collected reparation payments. (20)

The Soviet military administration seized firms that were owned by the Third Reich or Nazi collaborators.

They converted other firms into Soviet "corporations" and their products were destined solely for the Soviet

Union as reparation payments.

Engineering teams roamed over the Soviet zone dismantling and shipping to the Soviet Union everything from entire factories to toilets.

The Soviets also initiated land reforms, breaking up the large estates in eastern Germany and giving the land to small farmers or landless peasants.

Since the Soviets identified the capitalist system as responsible for the Third Reich, their policies

aimed at destroying this capitalist structure (and providing reparation payments to the Soviet Union at the same time).

Denazification

The Allied denazification programs sought to remove Nazi influences from German

society and politics as a necessary first step in creating a liberal, democratic state. (21)

These efforts began with the Nuremberg International Military Tribunal. The principal

surviving leaders of Nazi Germany were placed on trial for war crimes and crimes against

humanity, such as the mass murders in the concentration camps.

To some extent the German nation also stood in the docket and was forced to confront, often unwillingly, the horrors of the Third Reich.

The court returned guilt verdicts against the Nazi leadership and the institutions of the Nazi state (the SA, SS, SD, Gestapo, and Nazi party).

A second phase of denazification gradually expanded the program to

the German society in broader terms.

The Soviets concentrated their denazification

efforts on individuals who had occupied positions of economic or political influence in pre-1945 Germany.

Over 40,00 leading industrialists, landowners, military officers,

government officials, and NSDAP leaders were identified as active Nazis.

They were removed from office, their property was confiscated, and about a third were interred in Soviet labor camps.

In the West, the military governors arrested several thousand individuals who held posts in Nazi institutions.

In the American zone, the denazification program grew to include the public at large.

Every adult was required to fill out a questionnaire detailing past political activities.

These questionnaires (over 13 million) provided a basis for taking further action against individuals

who were closely involved with the Nazi movement.

Western denazification efforts are often criticized by contemporary historians.

Beyond removing the top level of Nazi leadership, the program had mixed effects in truly

ridding Nazi influences from German society. The application of the rules was imprecise

and varied greatly across occupation zones. The pragmatic needs for experienced

personnel to run the government and economy often conflicted with denazification goals.

Moreover, most Germans wanted to forget the experiences of the Third Reich,

and the Allies' stress on the collective guilt of the Germans created discontent and

increased hostility towards the occupation forces.

In the end, the administrative task of

screening all Germans in the American zone became impossible to manage and the program was deemphasized.

Yet given the inhumanity of the Third Reich, it would have been a graver error if the Allies had done nothing and let the world forget.

If not a sense of collective guilt, the Germans (and the world) felt a sense of collective shame over what

had happened during the Third Reich.

Visit an online library for the Nuremberg War Crimes Trial

"Democratization" in East and West

As soon as the immediate crises of postwar Germany were addressed, tensions between

the Allies resurfaced. Political and social developments within each occupation zone

followed diverging courses. The Potsdam conference in 1945 had called for

decentralization, local self-government, and representative institutions. Each of the Allies

interpreted these goals differently. (22) On the Soviet side, the political leadership was drawn

from communists who had spent the war in exile in the Soviet Union planning their postwar takeover. (23)

The first east German leader, Walter Ulbrich, rolled into Berlin just

behind the Russian tanks; the Communist Party (KPD) was refounded 5 days after the

Soviet military government took control.

Within a few weeks, the SPD, a Christian democratic party and a liberal party were formed.

Thus political life returned very quickly to the East, and under the apparent form of democratic party competition.

But the situation soon changed.

In the Spring of 1946 the SPD was forced into a

merger with the communists to create a new Socialist Unity Party (SED) in the eastern zone.

The SED enabled the communists to control their more numerous rivals.

As the Cold War heated up, the Stalinist ideological orientations of the SED strengthened.

The SED controlled the remaining political parties within a bloc of anti-fascist forces; dissident politicians were ousted.

The SED transformed itself into a Marxist-Leninist party, and by 1948 the Soviet zone had

essentially become a copy of the Soviet political system.