In recent years two small parties have also competed in elections. One is the Pirate Party which is an advocate for internet freedom, government transparency and reforming laws that restrict the sharing of information. The other is the Alternative for Germany (AfD) which is an anti-European Union party formed before the 2013 elections. The following sections describe the history and political orientations of the parties represented in recent Bundestags.

The Christian Democrats began as a new party in postwar West Germany. The Western occupation forces in postwar Germany recruited many moderate, reputable conservative politicians from the Weimar era to help rebuild of postwar German government. These conservative politicians began working for a non-socialist alternative to the rapidly growing Social Democratic party. Gradually, a patchwork of non-Left groups developed at the local level, and then developed regional and national networks.

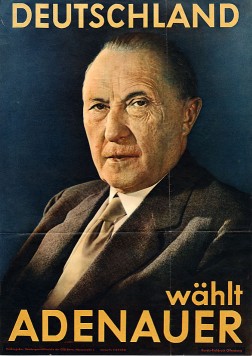

The central force in this loose conservative alliance was the Christian Democratic Union (CDU). The CDU represented a sharp break with the tradition of German conservative parties. The party was composed of a heterogeneous group of Catholics and Protestants, business people and trade unionists, conservatives and moderates. The party united behind the principle that West Germany should be reconstructed along Christian and humanitarian lines, without an exclusive Catholic or Protestant orientation. The CDU was anti-Nazi and anti-Communist, while extolling conservative values and the merits of the social market economy. Konrad Adenauer, the party's first leader, sought to develop the CDU into a conservative "catch-all party" (Volkspartei) appealing to a wide spectrum of the electorate–a sharp contrast to the fragmented ideological parties of the Weimar Republic.(7)

The CDU today is a national party, except for Bavaria where it allies itself with the Christian Social Union (CSU). The CSU reflects the strong regional identity of Bavarians as well as their more conservative political views. The two Union parties generally function as one in national politics. In national elections the CDU runs in every state except Bavaria, where only the CSU is present on the ballot. The Union parties campaign together under the CDU/CSU banner, form a single Fraktion in the Bundestag, and have always entered the government as a coalition.

The 1949 election surprised many analysts because the Union emerged as the largest single party and Adenauer built a coalition government to control the new state (Table 8.1). Adenauer rapidly emerged as the dominant figure in postwar West German politics. In many senses the CDU was Adenauer, and Adenauer was the party. The new government generally followed Adenauer's policy preferences, and the success of these programs further strengthened Adenauer's stature and the CDU’s electoral appeal. The Christian Democrats made impressive electoral gains in 1953, and in 1957 the Union (together with the CSU) became the first and only FRG party to ever win an absolute majority in a national election.

When the "old man," as he was (ir)reverently known, began to fade in the late 1950s, the party shared his struggle. Adenauer was 85 years old at the time of the 1961 election (more than a decade older than Reagan at his last election in 1984). The CDU/CSU won the 1961 election, but its lead over the opposition Social Democrats was cut nearly in half. After extended maneuvering, Ludwig Erhard replaced Adenauer as chancellor in 1963. Erhard was the architect of the Economic Miracle and a competent administrator, but he was unable to infuse the Christian Democrats with new vision once postwar recovery had been attained.

An economic recession in the mid-1960s brought the era of CDU/CSU dominance to an end. The FDP opposed the CDU/CSU's proposed economic reforms, and so the CDU/CSU joined with the Social Democrats to form the Grand Coalition in November 1966. The CDU/CSU and SPD shared governing responsibility; Kurt Georg Kiesinger was the CDU/CSU chancellor and Willy Brandt was the SPD vice chancellor. The cabinet positions were distributed between the two parties. Only the small Free Democratic party was left on the opposition benches. The Grand Coalition's economic policies generally reaped success, and by 1968 the nation was on the road to economic recovery.

In the 1969 election the voters had a difficult time distinguishing between the two major parties that had shared government control. Furthermore, until the election was over it was unclear whether the CDU/CSU and SPD would continue the Grand Coalition. When the votes were in, the SPD allied itself with the Free Democratic party and gained control of the government by a narrow margin of only 12 seats (Table 8.2). For the first time in the history of the Federal Republic, the CDU/CSU was in opposition.

The Christian Democrats were very uncomfortable on the hard seats of the opposition benches. The CDU/CSU was the largest party group in the Bundestag, and many party leaders considered the loss of power to be an unfortunate mistake or an unfair electoral manipulation by the SPD-FDP coalition. The Union parties thus emphasized their role as a shadow government, waiting for what they believed was their inevitable return to power. Yet, the CDU/CSU lacked a clear policy direction; party members did not always agree on how the party’s broad goals should be translated into specific policies.

The CDU/CSU's vote share decreased by less than 2 percent in 1972, but the party no longer could claim to be the largest party in the Bundestag. This event forced the party to reevaluate its position and to begin the long process of party rebuilding. The CDU expanded its membership base and developed the organizational resources of the national party. At the head of the national party was an aggressive young Minister-president from Rhineland-Pfalz, Helmut Kohl.

Buoyed by a rejuvenated party organization, Kohl ran as the CDU chancellor candidate in 1976. The CDU/CSU tried to capitalize upon the public's resurgent fears about economic and social conditions, and evoked the CDU/CSU's past glory. The CDU/CSU lost to the SPD-FDP coalition by the barest margin (1.9 percentage points). Because of this experience, Kohl realized the difficulty of winning an absolute majority, and so he advocated a centrist strategy that would attract moderate voters and possibly yield a new parliamentary coalition with the FDP. Others claimed that the CDU/CSU could win the votes of a "silent majority," if only the party would present a clear conservative option to attract these voters.

In 1980 the Union parties agreed to follow this second strategy. Franz Josef Strauss, head of the CSU, ran as the Union chancellor candidate against the popular SPD chancellor, Helmut Schmidt. Strauss vigorously attacked Schmidt, the SPD-FDP coalition, and their governing record (a record that most voters admired). Strauss' excessive conservatism and acerbic style alienated many traditional voters. The silent majority (if it existed) could not be found and the CDU/CSU suffered a decisive defeat. The CDU/CSU vote share dropped to its lowest level since 1949.

Perhaps the biggest winner of the 1980 election was Helmut Kohl. Kohl became the unchallenged leader of the opposition. Moreover, the CDU mapped out a new party program based on conservative economic policies derived from Thatcher and Reagan, along with moderate social and foreign policies. These policies increased the political compatibility between the CDU/CSU and FDP; ties that Kohl nurtured through his personal contacts with the FDP leadership.

Table 8.1 Party Shares of the Bundestag Vote (Second Vote), 1949-2013

| 1949 | 1953 | 1957 | 1961 | 1965 | 1969 | 1972 | 1976 | 1980 | 1983 | 1987 | 1990 | 1994 | 1998 | 2002 | 2005 | 2009 | 2013 | |

CDU/CSU |

31.0 | 45.2 | 50.2 | 45.4 | 47.6 | 46.1 | 44.8 | 48.6 | 44.5 | 48.8 | 44.3 | 43.8 | 41.5 | 35.2 | 38.5 | 34.2 | 33.8 | 41.5 |

| FDP | 11.9 | 9.5 | 7.7 | 12.8 | 9.5 | 5.8 | 8.4 | 7.9 | 10.6 | 7.0 | 9.1 | 11.0 | 6.9 | 6.2 | 7.4 | 9.8 | 14.6 | 4.8 |

| SPD | 29.2 | 28.8 | 31.8 | 36.2 | 39.3 | 42.7 | 45.9 | 42.6 | 42.9 | 38.2 | 37.0 | 33.5 | 36.4 | 40.9 | 38.5 | 34.2 | 23.0 | 25.7 |

Greens |

|

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

1.5 |

5.6 |

8.3 |

5.1 |

7.3 |

6.7 |

8.6 |

8.1 |

10.7 |

8.4 |

Linke/PDS |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

2.4 |

4.4 |

5.1 |

4.0 |

8.7 |

11.9 |

8.6 |

| Other parties | 27.9 | 16.5 |

10.3 |

5.6 |

3.6 |

5.4 |

0.9 |

0.9 |

0.5 |

0.4 |

1.3 |

4.2 |

3.6 |

6.0 |

3.0 |

3.9 |

6.2 |

11.0 |

| Total | 100% | 100% |

100% |

100% |

100% |

100% |

100% |

100% |

100% |

100% |

100% |

100% |

100% |

100% |

100% |

100% |

100% |

100% |

When the SPD-FDP governing coalition began to stumble in 1982, Kohl and the CDU/CSU were waiting in the wings. In mid 1982, the FDP leadership broke with the Social Democrats over economic policy, and formed a conservative alliance with the CDU/CSU. The first successful use of the constructive no confidence vote removed Helmut Schmidt from the chancellorship and replaced him with Helmut Kohl and a new CDU/CSU-FDP team. Elections in March 1983 endorsed the change in government and provided the CDU/CSU with a major electoral victory.

The Kohl government made substantial progress in addressing Germany's policy problems.

The government cut the budget deficit and the economy staged a substantial recovery.

The CDU/CSU-FDP government retained its majority in the 1987 election, but without

much enthusiasm on the part of the voters. A series of political scandals and declining economic

conditions decreased the party's popular support. The CDU was also challenged by a new

conservative party, the Republicans (Republikaner) that championed a more conservative and

nationalist program.(8)

The Kohl government made substantial progress in addressing Germany's policy problems.

The government cut the budget deficit and the economy staged a substantial recovery.

The CDU/CSU-FDP government retained its majority in the 1987 election, but without

much enthusiasm on the part of the voters. A series of political scandals and declining economic

conditions decreased the party's popular support. The CDU was also challenged by a new

conservative party, the Republicans (Republikaner) that championed a more conservative and

nationalist program.(8)

The collapse of the East German regime in 1989-90 surprised almost everyone in the West (and East). Kohl was one of the first to realize that this provided a historic opportunity for the CDU as well as Germany. While others looked upon the events with wonder or uncertainty, Kohl embraced the idea of closer ties between the two Germanies, leading to eventual confederation or unification. Thus, when the March 1990 GDR election became a referendum in support of German unification, this assured a Christian Democratic victory because of the party's early commitment to union. The CDU-led alliance won over 48 percent of the popular vote, and together with the Liberals they formed the new GDR government under Lothar de Maziere. In the December Bundestag election, Kohl rightly claimed that he (and the CDU) had been the moving force in German unification, and assured voters that no one would suffer from unification and Germany would prosper.

Table 8.2 Party Seats in the Bundestag, 1949-2013

|

1949 |

1953 |

1957 |

1961 |

1965 |

1969 |

1972 |

1976 |

1980 |

1983 |

1987 |

1990 |

1994 |

1998 |

2002 |

2005 |

2009 |

2013 |

| CDU/CSU | 139 |

243 |

270 |

242 |

245 |

242 |

225 |

243 |

226 |

244 |

223 |

319 |

294 |

245 |

248 |

226 |

239 |

311 |

| FDP | 52 |

48 |

41 |

67 |

49 |

30 |

41 |

39 |

53 |

34 |

46 |

79 |

47 |

43 |

47 |

61 |

93 |

0 |

| SPD | 131 |

151 |

169 |

190 |

202 |

224 |

230 |

214 |

218 |

193 |

186 |

239 |

252 |

298 |

251 |

222 |

146 |

193 |

| Greens | – |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

0 |

27 |

42 |

8 |

49 |

47 |

55 |

51 |

68 |

63 |

| Linke/PDS | – |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

17 |

30 |

36 |

2 |

54 |

76 |

64 |

| Other parties | 80 |

45 |

17 |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– | – |

| Total | 402 |

487 |

497 |

499 |

496 |

496 |

496 |

496 |

497 |

498 |

497 |

662 |

672 |

669 |

603 |

614 |

622 |

631 |

The parties forming the government after the election are shaded in the table.

Kohl was victorious in the 1990 Bundestag elections. But his government struggled with the policy challenges produced by German unification. Despite creating images of dramatic renovation in the East, the unification process was slow and costly. Almost immediately after the votes were counted, the government implemented tax increases to pay for the unification costs. Real progress was made, but less than promised and at a higher cost. The governing coalition lost more than 40 seats in the 1994 elections, but Kohl retained a slim majority.

By the 1998 elections, the accumulation of 16 years of governing and the special challenges of unification had taken their toll on the party and Helmut Kohl. Many Germans looked for a change. The CDU/CSU fared poorly in the election, especially in the Eastern Länder that were frustrated by their persisting second-class status. The CDU’s poor showing in the election was a rebuke to Kohl and he resigned the party leadership. After the elections investigators found that Kohl had accepted illegal campaign contributions while he was chancellor. Kohl’s allies within the CDU were forced to resign, and the party’s electoral fortunes suffered.

The CDU/CSU chose Edmund Stoiber, the head of the Christian Social Union, as its chancellor candidate in 2002. Stoiber’s campaign stressed the struggling German economy, and under his leadership the CDU/CSU gained the same vote share as the Social Democrats and nearly as many seats in the Bundestag. Although an SPD-led coalition retained control of the government, the CDU/CSU was a renewed force in German politics.

When early elections were called in 2005, the CDU/CSU selected Angela Merkel as their chancellor candidate (see box below). Merkel had learned politics from Helmut Kohl, but also openly criticized him during the party funding scandal. This improved her image among the German public, but not among CDU/CSU supporters. Merkel and the party ran ahead of the SPD throughout the campaign, and most observers expected a CDU victory. But the election ended as a dead heat between the CDU/CSU and SPD-and both Merkel and Schröder declared victory. After weeks of negotiation, the CDU/CSU and a Schröder-less SPD agreed to form a "Grand Coalition". This strange alliance was similar to the U.S. Democrats and Republicans sharing control of the government!

|

Merkel's style is far different from her predecessor. Instead of forcefully leading the government, her style is to consult and seek consensus. But consensus is difficult when the two large rival parties both form the government, and so little policy change came from the Grand Coalition. Even when the global economic downturn starting in 2008 severely challenged, Germany was slow to act and moved very cautiously. The government at first supported the banks in the fiscal crisis, but then began a cautious policy of tight spending. An even greater challenge was the growing monetary crisis of the Euro and the struggling economies of Southern Europe. Again, she responded cautiously in response to the conflict pressures on the government.

In 2009, voters preferred Merkel over her SPD challenger. The CDU/CSU lost a small share of the votes, but the FDP registered historic gains. A new center-right coalition of CDU/CSU and FDP formed after the election. It promises a new conservative program to deal with Germany's immediate policy challenges and its long-term needs for policy reform. But it was difficult to govern given the financial strains facing Germany, and tensions grew among coalition partners.

In 2013 Merkel's position as chancellor candidate was even more secure, but people vote for parties rather than individual candidates. The CDU/CSU increased its showing, but the small FDP lost its representation in the Bundestag. The new AfD party drew almost 5 percent of the votes, mostly from conservatives who might have voted CDU/CSU or FDP. For several months Merkel pursued negotiations to find a new coalition partner, finally reaching agreement with the SPD. The new grand coalition has the potential to address the policy challenges facing Germany, but it is unclear whether the conflicting ideologies of the coalition partners will allow the government to make real progress.

Social Democrats (SPD)(9)

The revival of the Social Democratic Party (SPD) started immediately after the war's end in 1945. Kurt Schumacher, the SPD leader, reconstructed the party along the lines of its Weimar predecessor. The new SPD defined itself as an ideological party, representing the interests of unions and the working class. The SPD's program was derived from Marxist doctrine, which included the nationalization of major industries and the implementation of state planning. Until his death in 1952, Schumacher consistently opposed Adenauer's Western-oriented foreign policy program, preferring reunification of the two Germanies even at the cost of accommodation with the Soviet Union. The SPD's initial image of the Federal Republic's future was radically different from that of the Christian Democrats.

The party's poor showing in the 1949 elections dashed its hopes for governing postwar Germany. The party gained some support in subsequent elections, but it seemed to be locked in the 30-percent range. The party's program appealed to the socialist core of the working class, but not to the wider spectrum of German society. Most Germans preferred the economic and foreign policies of the Christian Democrats over those proposed by the SPD. Reformers within the SPD lobbied for the party to shed its radical image and broaden its political appeal beyond the working class.

In 1959 the SPD undertook a historic change in course. At the Bad Godesberg conference the party abandoned its traditional role as advocate for socialism. In a single act, the party renounced its policies of nationalization and state planning, and embraced Keynesian economics and the principles of the social market economy. Karl Marx would have been surprised to read the Godesberg program and learn that market competition was one of the essential conditions of a social democratic economic policy. The SPD reached out to the churches and shed its opposition to NATO and the Western Alliance. The party still represented working-class interests, but the SPD hoped to attract new liberal middle class voters by dropping its ideological banner and more extreme policies. The SPD wanted to be a liberal-oriented catch-all party that could compete with the Christian Democrats.

The Godesberg Program marked a dramatic step toward a new political style for the SPD. With a young vibrant Willy Brandt leading the party as chancellor candidate, the SPD posted steady electoral gains. From its lowpoint in 1953, the Social Democrats enjoyed a nearly constant 3-percent gain from election to election in what came to be known as the "comrade trend." Still, the public still held doubts about the SPD's political reliability and capacity to govern. The party's past actions and policies led many people to conclude that the SPD opposed the basic goals of German society, a perception the CDU/CSU eagerly encouraged.(10)

The opportunity to change the party’s basic image arose in November 1966, when the CDU/CSU joined the SPD to form a Grand Coalition. The SPD not only improved its image of reliability and trust by sharing national governing responsibility, but it also played an active role in leading the Federal Republic out of the recession.

The SPD share of the popular vote in the 1969 election nearly reached parity with the CDU/CSU. More important, the small FDP aligned itself with the Social Democrats. This produced a new government coalition of the SPD and FDP with Willy Brandt as chancellor. The new coalition government adopted a program of political reform and modernization. The most dramatic initiatives came in foreign policy. Brandt proposed a fundamentally different policy toward the East (Ostpolitik), in which the Federal Republic accepted the postwar political divisions within Europe and sought reconciliation with the nations of Eastern Europe. The FRG signed treaties with the Soviet Union and Poland to resolve disagreements dating back to World War II and to establish new economic and diplomatic ties. In 1971 Brandt received the Nobel Peace prize for his actions. Finally, a "Basic Agreement" with East Germany formalized the relationship between the two Germanies.

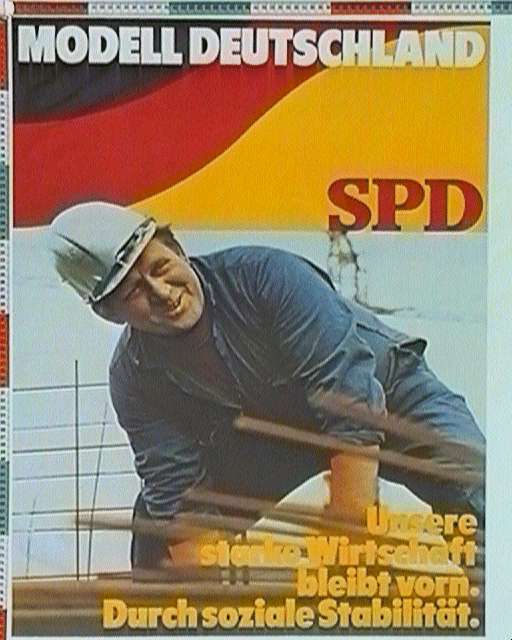

The SPD-FDP’s domestic policy reforms expanded social services and equalized access to the fruits of the Economic Miracle. The government broadened access to higher education, and generally improved the quality of the educational system. Social spending nearly doubled between 1969 and 1975; the government enacted new old age pension benefits, health insurance, and social services (see Chapter 10). Proud of these accomplishments, in the 1972 elections the SPD boasted that they were creating the "Modell Deutschland" that other European democracies could emulate.

The pace of social reform slacked in the mid-1970s, mainly as a result of the worldwide economic problems arising from the rising price of oil. The Federal Republic simultaneously suffered from economic stagnation and inflation. Willy Brandt left the chancellorship in 1974. The new SPD chancellor, Helmut Schmidt, directed a retrenchment on domestic policy reforms.

Although the SPD retained government control in the 1976 and 1980 elections, these were trying times for the party. The SPD and FDP frequently disagreed on how the government should respond to economic problems. Policy divisions also developed within the SPD.(11) For example, the SPD's traditional union supporters favored nuclear energy and a renewed emphasis on economic growth to lessen unemployment. At the same time, many young middle-class SPD supporters opposed nuclear energy and economic development projects that might threaten environmental quality. Other disagreements arose over defense policy, and the Federal Republic's willingness to accept a new generation of NATO nuclear missiles.

As the economic and political situation worsened in the months following the 1980 election, the governing parties struggled to deal with these problems. The Free Democrats eventually decided to switch coalition partners and ally themselves with the CDU/CSU. The SPD was forced out of office. The party suffered heavy losses in the 1983 election, and faced an identity crisis. The party was challenged on the left by the Greens and on the right by the Christian-Liberal government. Should the party attempt to accommodate the Greens or adopt a centrist program in competition with the government? In 1987 the SPD followed a centrist strategy, but did not significantly improve the party's vote share. In 1990 they planned to appeal to the liberal, middle-class voters, but the SPD's campaign was overtaken by events in the East.

Perhaps no one, except maybe the Communists, were more surprised than the SPD by the course of events in the GDR in 1989. The SPD had been normalizing relations with the SED as a basis of intra-German cooperation, only to see the SED ousted by the citizenry. The SPD and its chancellor candidate, Oskar Lafontaine, were ambivalent about German unification, and stood by quietly as Kohl spoke of a single German Vaterland to crowds of applauding East Germans. The SPD expected the East to be a bastion of socialist support because of Weimar voting patterns, and saw the Christian Democrats capture the votes of this new constituency. The SPD's poor performance in the 1990 Bundestag elections reflected the party's inability to either lead or follow the course of the unification process.

Frustrated by Germany's course after unification, the public came to the brink of voting the SPD into office in 1994, and then pulled back. Then, in the spring of 1998, the Social Democrats selected Gerhard Schröder to be their chancellor candidate. Representing the moderate wing of the party, Schröder attracted former CDU/CSU and Free Democratic voters who were disenchanted with the government’s performance. The SPD made broad gains in the 1998 election and formed a new coalition government with the environmental Green Party. Schröder pursued a middle course, balancing the centrist and leftist views within the coalition. For instance, overdue reductions in tax rates and government spending were paired with a new environmental tax advocated by the Greens. The government allowed German troops to play an active role in Kosovo and Afghanistan, while mandating the phasing out of nuclear power.

As the 2002 election approached, however, the German economy was struggling and the SPD-led government was behind in the polls. Schröder deflected criticism of his economic policy and opposed American policy toward Iraq to gain new votes from easterners and take votes from the PDS. This strategy worked, and the SPD-Green government gained a small majority and returned to office. But as soon as the election was over, the new government again began to struggle.

In early 2005 Schröder called for new elections. This was a gamble. Schröder hoped that disarray among his opponents would allow him to win one more election on the strength of his personal image. At first, his planned seemed to go awry. The CDU/CSU united behind Merkel's candidacy, and she moved up in the polls. Even worse, a group of dissident Social Democrats in the West united with the PDS in the East, which threatened to siphon votes away from the SPD. Schröder ran a dynamic campaign, and surprised analysts by closing the gap with the CDU/CSU. On election night, the post-election forecasts were unsure which was the largest party because the votes were so close (see Table 8.1)

Schröder initially claimed victory since the SPD's vote share equaled the CDU/CSU's. But the electoral math did not add up. The SPD negotiated with the CDU to form a grand coalition, because the splintering of the vote to smaller parties made other coalition options more difficult. An SPD leader has served as vice chancellor in the new government, and the two large parties theoretically share the responsibility of government. This was a difficult relationship for the SPD, and the party struggles to balance its liberal ideals against the policies of Merkel and the CDU/CSU. The party suffered severe losses in the 2009 election (see Table 8.1), in part a backlash to its participation in the Grand Coalition. Many leftist voters supported either the Linke or the Greens. Now in opposition, the party must reassess how it competes in the more fragemented party system of contemporary Germany.

As an opposition party, the SPD increased its vote share slightly since 2009. In fact, the leftist parties--SPD, Greens and Linke--help a majority of seats in the Bundestag. However, the SPD had excluded cooperation with the Linke because of its communist roots. So after months of negotiations, it again found itself in a grand coalition. Like a married couple that had divorced earlier, the SPD choose to renew its vows to the Christian Democrats. But what is uncertain is whether this marriage will repeat the problems of the past, leaving the SPD struggling as it had after the previous grand coalition. Or will this tryst rejuvenate the party?

Free Democrats (FDP)(12)

The Free Democratic party (FDP) was created in 1948 to continue the liberal party tradition from prewar Germany. The party has a distinct political philosophy. The party positioned itself as an alternative to both the CDU/CSU and SPD. The party is a strong advocate of private enterprise and opposes some of the more liberal economic policies of the SPD. At the same time, the FDP's liberal social policies contrast with the Christian orientation of the Union parties. The FDP was for "people who found the CDU too close to the churches and the SPD too close to the trade unions."(13) The party drew much of its initial electoral support from business interests, the Protestant middle class, and farmers.

The FDP was one of the first four parties licensed by the occupation forces, and it used this early start to win representation in the preliminary round of state and local elections. The party emerged from the 1949 elections as the third largest party in the Bundestag. From 1949 until 1957, and again from 1961 until 1966, the FDP was the junior coalition partner of the CDU/CSU. As part of the government the FDP advocated policies aimed at stimulating postwar economic development, represented the interests of agriculture, and endorsed Adenauer's Western-oriented foreign policy.

In the late 1960s the Free Democrats developed a new party image on non-economic issues. This transformation led to the decision to form a new alliance with the SPD after the 1969 Bundestag elections. The party called for the democratization of society, social reforms, and more socially-minded economic policies. The party supported Brandt's Ostpolitik, and the two governing parties worked closely together on social modernization policies. The F.D.P.'s public image and prestige steadily grew. Walter Scheel, the F.D.P. leader, became Federal President in 1974, and Hans-Dietrich Genscher took over the party helm.

With the worsening of economic conditions in the early 1980s, the Free Democrats reasserted their conservative economic policies, which moved them closer to the CDU/CSU. The Free Democrats' secretly planned to dissolve their marriage with the Social Democrats and renew their earlier bonds with the CDU/CSU. In September 1982 the coalition came to an end, and the FDP formed a new government with the CDU/CSU.

Each previous time the FDP had changed direction, in 1957 and 1969, the party had suffered at the polls, and the same thing happened in 1983 (see Table 8.1). The party's vote share dropped from 10.6 percent in 1980 to 6.9 percent in 1983, barely enough to earn seats in the Bundestag. Just as political analysts were preparing eulogies for the FDP, the party made a dramatic recovery. The Free Democrats pressed for fiscal policies to lessen the federal deficit and restore economic growth. Foreign minister Genscher won public favor by continuing to advocate detente with the East. The Free Democrats were a moderating force on the CDU/CSU. The FDP thus gained votes from both the CDU and SPD in the 1987 election. Analysts interpreted the results as a sign that the public wanted to strengthen the FDP's position as a moderating influence on the Union parties.

The FDP benefitted from its support of unification and the positive role that Genscher played in this process. The party received sufficient support to continue its coalition with the CDU/CSU after the 1990 and 1994 election. Then it took to the opposition benches when the SPD-Green coalition won in 1998.

In 2001 Guido Westerwelle won the party leadership; his goal is to return the FDP to a role in the national government. The party was the clearest advocate for many of the economic and social reforms that many analysts favored. However, internal party divisions harmed the party’s standing in 2002, and its poor showing kept the conservative CDU/CSU-FDP coalition from winning the election. In 2005 the CDU/CSU formed a grand coalition, leaving the FDP out in the cold. The party used its time on the opposition benches to strengthen its appeal to the voters. In 2009 the party gained its higher share of the vote in its history, and once again entered government in coalition with the CDU/CSU.

The FDP's record underscores the potential importance of small parties in a multiparty system. Although the FDP is the smallest of the established parties, its influence in the party system has greatly outweighed its share of the popular vote. Government control in the German parliamentary system, at the federal and state levels, routinely requires a coalition of parties. The FDP has often controled enough votes and a strategic centrist ideological position to play a pivotal role in forming government coalitions and direct the course of politics. But living small is risky. Pundits predicted the FDP would fail to win representation in several previous elections. It always proved the pundits wrong-until 2013. The party fell a fraction below the five percent required for representation in the Bundestag. Now the party has to regroup at the state and local level to offer voters a better choice at the next election, if it is to regain national representation.

The Greens(14)

Environmental issues first attracted widespread public attention in the late 1960s and early 1970s. As the Federal Republic enjoyed the products of the Economic Miracle, some citizens grew concerned about mounting environmental problems. The catalyst for citizen concern was often a local problem, pollution by a local company or the construction of a nuclear power plant. Because the established parties generally were unresponsive to these issues, environmentalists organized citizen action groups outside the party system to lobby on environmental issues.

In the late 1970s the environmental movement entered a new phase. Frustrated by the lack of progress in working from outside the political system, local and regional ecological groups started to work for change from inside the system. The first environmental lists appeared in the 1977 local elections in Schleswig-Holstein. Within a year, environmental parties were sprouting up across the Länder.

In 1980, The Greens (Die Grünen) were created. The Greens proclaimed themselves as a party of a new type, advocating a society in harmony with nature and a party free of bureaucratic structures. At the outset the party was a multicolored rainbow. It attracted a heterogeneous mixture of students, farmers, and middle class supporters. Prominent figures within the party ranged from a former CDU Bundestag deputy to former Maoists, from a retired army general to a convicted student terrorist.

The Greens fared poorly in the 1980 election, but by the end of 1982 the Greens had won seats in six state legislatures. The party also developed a more extensive political program that included issues such as support for women's rights, minority rights, and the further democratization of society and the economy. This new ideological focus drove many conservative members out of the party, as the Greens became a representative of New Left and alternative political viewpoints. The party's 1983 election manifesto called for predictable environmental policies such as the immediate halt of all nuclear power activity, the dismantling of nuclear power plants, and the elimination of pesticides from agriculture. In addition, the Greens called for more unconventional policies: prohibition on the sale of war toys; the immediate abolition of TV and radio advertisements as well as all advertisements for cigarettes, candy, liquor, and agricultural chemicals; mandatory home economics and child-rearing classes for both male and female students; an end to discrimination against homosexuals and lesbians; the elimination of assembly-line work and night shifts; and the conversion of the German arms industry to the production of energy and environmental systems. The Greens represented a new political philosophy in partisan politics.

In the 1983 elections the Greens emphasized the issues of environmental protection and nuclear weapons. Riding on these two issues, the Greens won 27 seats in the Bundestag with 5.6 percent of the vote. Using their new political forum, the Greens vigorously campaigned for an alternative political view on the environment, defense policy, citizen participation, and minority rights. At the same time, the Greens added a bit of color and spontaneity to the normally staid procedures of the political system. The Greens were a party of youthful exuberance.(15) They celebrated their entry into the Bundestag with a rag-tag parade of deputies and their supporters. The normal dress for Green deputies is jeans and a sweater, rather than the traditional business attire of the established parties. Many political analysts initially expressed dire concerns about the Greens impact of the political system, but experts now generally agree that the party was instrumental in bringing attention to new political viewpoints. Based on this performance, the Greens increased their share of the popular vote to in the 1987 elections.

Internally, the party was divided between "Fundis" (fundamentalists) and "Realos" (realists). The Fundis believed the party should maintain an uncompromising commitment to a radical restructuring of society and politics. Purity of thought and action–and eventually radical social change–is more important than short term results. The Realos were more pragmatic. They were willing to work within established channels for incremental social reform, even accepting positions in local and state governments. The factional battles between Fundis and Realos created an ongoing identity crisis for the Greens.

The Greens were initially ambivalent in responding to the East German revolution in 1989 because they opposed the simple eastward extension of the FRG’s economic and political systems. Even worse, some Green party leaders advocated an alliance with the recently dethroned communists in the East. Furthermore, to stress their opposition to the fusion of both Germanies, the Western Greens refused to develop a formal electoral alliance with any eastern party until after the 1990 elections. Separate Green slates ran in the West and in the East. The Eastern coalition of the Greens and Alliance '90 won enough votes to gain 8 seats in the Bundestag. However, the Western Greens failed to win any parliamentary seats on its own. The Greens unconventional politics finally caught up with them, at least temporarily.

The 1990 election results increased the factional conflict between Fundis and Realos, which the realists won. The Greens swept away many of its unconventional organizational structures and moved toward more pragmatic political style. These actions evoked the wrath of the Fundis, but it yielded strong showings for the Greens in subsequent state elections. The party reentered the Bundestag in 1994.

In 1998 the Green Party and asked voters to support a new Red-Green coalition of SPD and the Greens. This Red-Green coalition received a majority in the election, and for the first time the Greens became part of the national government. It is difficult to be an outsider when one is inside of the establishment, however. The antiparty party struggled to balance its unconventional policies against the new responsibilities of governing—and steadily gave up its unconventional style. For instance, the party supported military intervention into Kosovo, despite its pacifist traditions. It supported tax reform that lowered the highest rates in exchange for a new environmental tax. It pressed for the abolition of nuclear power, but agreed to wait thirty years for this to happen.

In the 2002 campaign, the anti-elitist Greens ran a campaign heavily based on the personal appeal of their leader, Joschka Fischer. The Greens’ success in 2002 is what returned the Schröder government to power. The Greens had become a conventional party in terms of their style, now pursuing unconventional and reformist policies.

The Greens gained votes in 2005, but were left out of the eventual governing coalition. The Greens standing increased in the 2009 election with its highest vote share ever. The Greens have become a conventional party in terms of their style, pursuing unconventional and reformist policies as a critique of the CDU/CSU-SPD alliance.

Party of Democratic Socialism (PDS) to Die Linke(16)

The party system of the German Democratic Republic reflected the contrast between political rhetoric and reality found throughout the system. The GDR ostensibly was a multiparty democracy, but the Communists held the rein of power very tightly.(17) To consolidate their control over society, the Soviets forced a merger of the Communist and Socialist parties into a new Socialist Unity Party of Germany (SED) in 1946. The SED was the ruling institution in the East. The state controlled East Germany society, and the SED controlled the state.

When the East German political system collapsed in 1989, the SED was drawn into this void. Membership in the SED plummeted and whole local and regional party units abolished themselves. The omnipotent party suddenly seemed impotent. In an attempt to remain competitive in the new democratic environment in the East, the party changed its name in February 1990 and became the Party of Democratic Socialism (PDS).

New moderates ousted the old party guard and took over the leadership of the PDS. In the 1990 Bundestag elections, the PDS was the only significant new party actor from the East. The PDS gained 11 percent of the eastern vote, which enabled it win seats in the new all-German parliament. The PDS became an advocate for Easterners who felt overlooked in the unification process. The PDS shared in the proportional distribution of Bundestag seats after the 1994 and 1998 elections.

The PDS faced an uncertain future following the 2002 election. The party held only two seats in the Bundestag and gained less than 5 percent of the national vote. The PDS suffered partly because of internal party divisions and partly because the SPD consciously sought the support of former PDS voters in the East. Many analysts predicted the eventual end of the party as a national political force.

As the 2005 election approached, the party's fate took a new turn. As alienation from Schroeder's government increased within SPD ranks, Oskar Lafontione (the SPD's chancellor candidate in 1990), proposed a new political alliance. The PDS in the East joined with new leftist elements of the SPD in the West. This alliance, PDS/Linke ran an joint slate in the 2005 elections and won 54 seats in the Bundestag. This allowed the party to play a spoiler role in the precluding the formation of either an SPD-Green or CDU/CSU-FDP government. Ironically, the Linke/PDS success resulted in the Grand Coalition.

In June 2007 the two parties formally merged and now function under the label "Die Linke" (the Left Party). The Linke is an alliance of easterners who are dissatisfied with their situation, and far left voters from the West. In the East, it is supplanting the SPD as the main leftist party. In the West, it draws support from the SPD which is seen as too moderate, especially after its coalition government with the CDU/CSU. The Linke's strong showing in 2009 and 2013 suggests the party has institutionalized itself as another member of the party system.

One of the most essential functions of political parties in a democracy is the selection of political elites. Elections give individuals and social groups with an opportunity to select officeholders who share their views. In turn, this choice leads to the representation of group interests in the policy process, because a party must be responsive to its electoral coalition if it wants to retain its voting support. While Bundestag deputies are selected in free and competitive contests, the structure of the German electoral system differs decidedly from the American or British system.

During elections in Germany, the government provides a limited amount of free

advertising to political parties on television and radio. These ads were traditional shown as a bloc before the prime

time television started in the evening. The parties have 1-5 minutes to present their message. Other ads run in the movie theaters before

the previews of coming attractions. As a result, these party ads typically tell a story, rather than offer a few short soundbites.

Many of ads for past elections have been uploaded to YouTube. Interestingly, the leftist parties--PDS, Greens and SPD--have been more

eager to post their ads, while the CDU has not yet added their ads to this collection.

The ads are in German, but they are still interesting if you don't speak German because they are visually so

different from American campaign ads. My favorites--for videography and style rather than political content--are marked by an asterisk. |

Electoral System

The framers of the Basic Law had two goals in mind when they designed the electoral system. One was to reinstate the proportional representation (PR) system that was used in the Weimar Republic. A PR system allocates legislative seats on the basis of a party's percentage of the popular votes. If a party receives 10 percentage of the popular vote it should receive 10 percent of the Bundestag seats. Other experts saw advantages in a system of single-member districts as used in Britain and the United States. They thought that this system would avoid the fragmentation of the Weimar party system and ensure greater accountability between an electoral district and its representative.

To satisfy both objectives, a hybrid system of "personalized proportional representation" was developed with elements of both models.(18) When a German votes in Bundestag elections he or she casts two votes (see sample ballot). The first vote (Erststimme) goes to a candidate running to represent the district. The candidate with the most votes is elected as the district representative. The Federal Republic is divided into 299 electoral districts of approximately 200,000 voters each. Half of the Bundestag deputies are directly elected from these districts.

With their second vote Zweitstimme) people select a party and thse votes determine the overall distribution of the parties in parliament. These second votes are added nationwide to determine each party's share of the popular vote. A party's proportion of the second vote determines its total representation in the Bundestag. Each party is allocated additional seats so that its percentage of the combined district and party seats equals its share of the vote. The additional party seats are distributed according to lists prepared by the state parties before the election.(19) Half of the members of the Bundestag, 299 deputies, are elected as party representatives.

One major exception to this PR system is the 5 percent clause. The electoral law stipulates that a party must win at least 5 percent of the national vote, or three constituency seats, to share in the distribution of party-list seats. The Framers designed the 5 percent law to avoid the growth of small extremist parties that plagued the Weimar Republic.(20) In practice, however, this electoral hurdle has handicapped all minor parties and contributed to the consolidation of the party system. People do not want to risk their votes on a small party if they fear it will fall below the 5 percent mark.(21) The FDP suffered this fate in 2013.

The party-list system also gives party leaders substantial influence over who will be elected to the Bundestag by the placement of candidates on the list. The lists are headed by prominent and popular figures within the party; they are virtually assured of election because positions near the top of the list carry a high likelihood of election, lower positions have only symbolic value. Each party attempts to represent the major political factions on the party list in proportion to their influence; the CDU takes this even a step further, enforcing a strict Proporz system to ensure that the number of Catholic and Protestant candidates is balanced. The various social interests within a party (such as business, labor, agriculture, and youth groups) receive list positions in keeping with their party rank. And recently, most of the parties have implemented standards to ensure women are well-represented in the electoral lists. The organization of the party lists thus provides unusual insights into the distribution of political power within a party.

The PR system also ensures fair representation for the smaller parties. The FDP has won only one direct candidate mandate since 1957, and yet it historically receives Bundestag seats based on its national share of the vote. In contrast, Great Britain's district-only system discriminates against small parties; in 2005 the British Liberal party won 22 percent of the national vote, but less than 10 percent of the parliamentary seats. Without proportional representation, the Greens and the Linke would not be in the Bundestag.

The German two-vote system also affects campaign strategies. Although most voters cast both their ballots for the same party, the smaller parties typically encourage supporters of the larger parties to "lend" their second decisive votes to them. Finally, research indicates that district and party representatives behave differently in the Bundestag. District candidates are somewhat more responsive to their constituents' needs, and are slightly more likely to follow their district's views when voting on legislation.(22)

The Contemporary Party Alignment

The social and economic divisions between the major parties were sharply drawn during the Federal Republic's early years.(23) The traditional split between the middle class and working class had deep roots in German politics; after all, Marx and Engels had based their revolutionary theories partially on the German experience. Religious antagonisms were just as intense, and just as closely linked to the political system. The major parties based their electoral appeals on these social divisions. In such an environment an individual could easily decide how to vote depending on his or her position in the social structure. Most members of the working class supported the SPD, while a majority of Catholics voted for the Christian parties. The small FDP has its own social identity, tied to the Protestant members of the middle class and farmers. Social networks were closely drawn and voters listened to the advice of the unions or church leaders in making their electoral decisions. Voting behavior studies found that social characteristics were potent predictors of voting patterns in the early Bundestag elections.(24)

The social transformation of Germany and the conscious actions of the parties lessened these social divisions over the next two decades. Affluence, social mobility, geographic mobility, and changing life styles diminished these traditional group and institutional networks. Party actions also promoted the decline of these traditional cleavages. As a result, political differences gradually narrowed as both the CDU/CSU and SPD became catch-all parties. In broadening their electoral coalitions, the major parties blurred the social bases of party support. Class voting differences in recent elections are but a shadow of earlier class polarization, and most other social divisions have similarly narrowed.(25)

Electoral choice has been understandably fluid among voters in the East. For example, it was difficult for eastern voters to fit into the class structures of the West. Eastern workers should have voted for the Left on class terms, but they were alienated from the politics of the GDR and drawn to the CDU for its role in the democratic transition. Similarly, many members of the middle class in the East had been SED party functionaries, governmental appointees, and managers of state enterprises. Thus, in the first Bundestag elections, the traditional class voting patterns of the West were reversed in the East, although this has changed since 2002.(26)

Unification also changed the religious balance of politics in the Federal Republic; Catholics and Protestants are roughly at parity in the West, but the East is heavily Protestant. In addition, the GDR government had successfully promoted the secularization of society during its forty year rule. For instance, a 1991 opinion poll found that 59 percent of Westerners never doubted the existence of God, compared to only 27 percent of Easterners.(27) Thus, religious cues were also an uncertain basis of voting choice in the East.

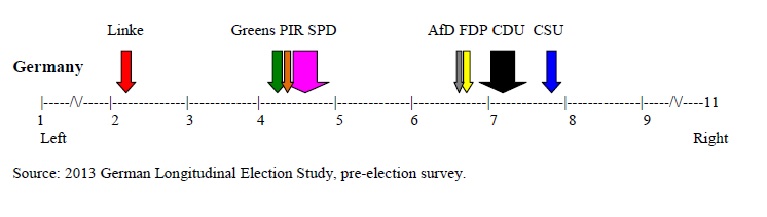

As we have noted, German voters face a wide range of political choices when they go to the polls. Figure 8.1 provides a summary of the party choices available in the 2013 election. The survey asked a sample of Germans to position each party on a Left/Right scale. "Left" is typically associated with the economic concerns of the working class, liberal social programs, and a larger role for the state; and more recently with support for environmental protection, women's rights, multiculturalism, and other postmaterial goals. "Right" is typically associations with support for middle class interests, religious values, and a smaller role of government; and recently with conservative views of immigration and national identity issues.

Figure 8.1 Left/Right Placement of the Parties in 2013

The size of the arrows in the figure is roughly proportionate to the party's vote share in the election. Their position along the Left/Right scale is based on the public's perception of the party's position. The diversity of the party landscape is the first obvious point. The Linke is located far to the Left of the other parties, reflecting its heritage as the reformed communist party. The Greens are the next party on the Left, although in this case it reflects their attention to postmaterial issues more than traditional economic and class issues. The small Pirate Party is located between the Greens and the SPD. The Social Democrats are the major party on the Left, and in cross-national terms are distinctly more leftist than the American Democratic Party or the British Labour party. The FDP and the new AfD are located to the right of the center. The CDU is positioned on the Right of the party spectrum, and its CSU sister party is further to its right.

This is the range of party choices that faces the German voter at election time. From one election to the next, the parties may shift slightly to the Left or the Right in reaction to contemporary events, or the voters themselves may change. But one reason that party government functions so well in Germany is that voters have a distinct set of options from which to choose, and with many parties one is likely to represent their policy preferences.

Voting Patterns

Voting alignments in the 2005 Bundestag election mix the electoral trends in the West, with the new voting patterns of Eastern voters. Table 8.3 describes the group bases of voter support for each party in the election, based on the total national electorate. The Christian Democrats draw disproportionate support from the conservative sectors of society. Catholics, the middle class voters, seniors, and residents of smaller towns are a substantial portion of the party's electoral coalition. For instance, about 35 percent of the entire electorate are Catholics, but Catholics comprise 44 percent of the CDU/CSU voters. The SPD's voter base is almost a mirror image of the CDU/CSU's. A larger share of the party's voters come from the working class households, and from non-religious voters.

The Greens have a distinct electoral base. Green voters are heavily drawn from the groups identified with the New Politics movement. The party represents the better-educated, non-religious, and urban voters. The age differences in party support are also substantial; almost half (43 percent) Green voters are under forty, although the proportion of young voters has decreased over time as the party itself has “aged”.

The PDS/Linke also have a distinct electoral base. The PDS wing of the party draws disproportionate support from the East. The party draws disproportionate support from non-religious voters and working class families.

TABLE 8.3 Electoral Coalitions of the Parties in the 2013 Federal Elections

|

CDU/CSU |

SPD | Greens |

Linke |

FDP |

Other |

| Region | ||||||

| West | 42 | 27 | 9 | 6 | 6 | 10 |

| East | 39 | 17 | 5 | 23 | 3 | 13 |

Occupation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Worker |

38 |

30 |

5 |

11 |

3 |

13 |

Self-employed |

48 |

15 |

10 |

7 |

10 |

10 |

White collar |

41 |

26 |

10 |

8 |

5 |

10 |

Civil servant |

44 |

25 |

13 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

Education |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Primary |

46 |

30 |

4 |

7 |

3 |

10 |

Secondary |

43 |

25 |

6 |

10 |

4 |

12 |

Abitur |

39 |

24 |

11 |

8 |

5 |

18 |

University |

37 |

23 |

15 |

9 |

7 |

9 |

Employment Status |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Employed |

40 |

26 |

10 |

8 |

5 |

12 |

Unemployed |

22 |

25 |

10 |

21 |

2 |

20 |

Retired |

48 |

29 |

5 |

9 |

4 |

5 |

Age |

|

|

|

|

| |

Under 30 |

34 |

24 |

11 |

8 |

5 |

18 |

30-44 |

41 |

22 |

10 |

8 |

5 |

14 |

45-59 |

39 |

27 |

10 |

9 |

5 |

10 |

60 and older |

49 |

28 |

5 |

8 |

5 |

5 |

Gender |

|

|

|

|

| |

Male |

39 |

27 |

8 |

8 |

4 |

13 |

Female |

44 |

24 |

10 |

8 |

5 |

10 |

Source: Regional data are from election statistics; social group information is from 2013 Bundestagswahl exit poll, Forschungsgruppe Wahlen. Percentages sum to 100 percent along the rows.

The centrality of political parties in the German political process means that the health and effectiveness of parties is a crucial part of the democratic process. And while parties are still central political actors, there are increasing signs of stress in the German system of party government.

In recent decades the German parties have struggled with a series of difficulty, and seemingly intractable policy challenges (see Chapter 10). In the 1980s, the Kohl government struggled to balance the needs for economic growth against the preservation of social services. In the 1990s, the historic achievement of unification was partially overshadowed by the economic collapse of the East and the difficulties of maintaining government programs in the face of these new demands. Today, the nation is still dealing with many of these same problems. Most analysts still believe the government has done too little to address the need for structural reforms in the economy and social welfare systems. Easterners are especially critical of the course of unification. Each election parties promise to resolve these problems, but the problems persist even when a new government is elected, and thus voters become frustrated with the parties' performance.((28)

The apparent rise in party scandals over the past two decades is another problem area.(29) Party scandals during the 1980s so distressed President von Weizsäcker, that he described politicians and political parties as ‘power-crazed for electoral victory and powerless when it comes to understanding the content and ideas required of political leadership’.(30) The nadir was reached when Helmut Kohl was accused of accepting illegal contributions to the CDU; he refused to divulge the source of these funds, which led to mass resignations from the CDU leadership.

These developments have stimulated growing public skepticism about political parties and the general system of party government. For instance, Enmid surveys show that the proportion of Germans who express confidence in the political parties has decreased from 43 percent in 1979 to only 26 percent in 1993.(31) The German election studies have tracked a downward trend in the percent of the German public that identifies with any political party. In 1972, only 19 percent of Westerners lacked a party attachment, and this increased to 41 percent by the 2009 election (and 46 percent in the East). And more recently, a survey of public trust in various organizations found that only 11 percent of the German public trusted political parties-the lowest trust level of any of the fourteen organizations included in the survey.((32) Skepticism is even greater among Easterners. Thus, the German public appears to be losing faith in specific political parties and possibly the general system of party government.

This distrust has consequences for the political system. For instance, Chapter 4 noted that turnout in Bundestag and Länder elections has been trending downward since the 1980s, even if participation increased a bit in the 2013 election. Participation in various campaign activities has also trended downward. Other statistics document the decline in party membership over the past two decades. If people are skeptical about parties, there is less motivation to engage in partisan politics.

These strains are prompting attempts at party reform. Within the parties, party activists are calling for greater influence by the rank and file. For instance, in 1998 the Social Democrats had an informal primary to select their chancellor candidate. There are also calls to give greater weight to constituency organizations and party membership conventions in setting party policies. Those who are not formal party members–about 90 percent of the electorate–have even less impact on party actions. And the party finance scandals have stimulated reforms for more transparency in party funding. But still today, party decisions typically flow from the top down–further distancing the public from the party organization.

Even more broadly, there is growing demand for new forms of direct participation that do not depend on the mediating role of parties, such as participation in citizen action groups and public interest groups. All the new Länder in the East included provisions for public initiatives in the state constitutions; citizens and political groups are increasingly using these forms of direct democracy at the state and local levels. The distinguished German scholar, Ralf Dahrendorf, has recently observed: “representative government is no longer as compelling a proposition as it once was. Instead, a search for new institutional forms to express conflicts of interest has begun”.(33) Citizens want parties to be more democratic, and democracy to mean more than just party government.

It is highly unlikely that parties will lose their unique position as intermediaries between citizens and the political process. But political parties cannot rest on their prior achievements. Changes in their internal structure and the larger political context suggest that parties no longer exert the internal control and external influence that they once possessed. This situation represents no so much the decline of parties as a growing competition from other political actors such as interest groups and citizen initiatives.

| Catch-all party | Free Democratic Party (FDP | Proportional representation (PR) |

| Christian Democratic Union (CDU) | Godesberg program | Republikaner |

| Christian Social Union (CSU) | Grand coalition | Second vote |

| First vote | Greens | Social Democratic Party (SPD) |

| Five percent clause | Linke | |

| Fraktionen | Party of Democratic Socialism (PDS) | |

Anderson, Christopher, and Carsten Zelle, eds. Stability and Change in German Elections: How Electorates Merge, Converge, or Collide. Westport, CT: Praeger, 1998.

Clemens, Clayton, and Thomas Saalfeld, eds. The 2005 Bundestagswahl, a special issue of German Politics (December 2006) 15: 335-535.

Conradt, David, Gerald R. Kleinfeld, Christian Søe, eds. Precarious Victory: The 2002 German Federal Election and its Aftermath. New York: Berghahn Books, 2005.

Langenbacher, E. ed., Between Left and Right: The 2009 Bundestag Elections and the Transformation of the German Party System. Brooklyn, NY: Berghahn, 2010.

Lees, Charles. The Red-Green Coalition in Germany: Politics, Personalities, and Power. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2000.

Mayer, Margit, and John Ely, eds. The German Greens: Paradox Between Movement and Party. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1998.

Poguntke, Thomas. Alternative Politics: The German Green Party. Edinburgh: University of Edinburgh Press, 1993.

Rohrschneider, Robert, ed. "Germany's Federal Election, September 2009," Symposium in Electoral Studies (2011) volume 31.

Stoess, Richard. Politics Against Democracy: The Extreme Right in West Germany. New York and Oxford: Berg Publishers, 1991.

Thomassen, Jacques, ed. The European Voter. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.

Notes

1. Karl Rohe, Elections, Parties and Political Traditions (Oxford: Berg Publishers, 1990); Gerhard Loewenberg, "The Remaking of the German Party System." In Karl Cerny, ed. Germany at the Polls (Washington: American Enterprise Institute, 1979).

2. Small extremist parties on the right and left challenged this consensus but the garnered few votes. Eventually the failure of these extremist parties to endorse the democratic consensus led to the courts banning the neo-Nazi Socialist Reich party as unconstitutional in 1952 and the Communist party in 1956.

3. Kenneth Dyson, "Party Government and Party State." In Herbert Döring and Gordon Smith, eds. Party Government and Political Culture in Western Germany (New York: St. Martin's, 1982), p. 84.

4. Gordon Smith, Democracy in Western Germany, 2nd ed. (New York: Holmes and Meier, 1982); Döring and Smith, ed. Party Government and Political Culture in Western Germany; Russell Dalton, David Farrell and Ian McAllister, Political Parties and Democratic Linkage. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011).

5. Kurt Sontheimer, The Government and Politics of West Germany (New York: Praeger, 1973), p. 95.

6. Geoffrey Pridham, Christian Democracy in Western Germany (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1977).

7. See Otto Kirchheimer "Germany: The Vanishing Opposition." In Robert Dahl, ed. Political Oppositions in Western Democracies (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1966).

8. Richard Stöss, Politics Against Democracy: The Extreme Right in West Germany (Oxford: Berg Publishers, 1991).

9. Gerard Braunthal, The West German Social Democrats, 1969-1982 (Boulder: Westview Press, 1983); Douglas Chalmers, The Social Democratic Party of Germany (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1966).

10. Although the SPD's opposition to the Third Reich may have partially rehabilitated its image, popular doubts about the party soon returned. See Kendall Baker; Russell Dalton; and Kai Hildebrandt, Germany Transformed (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1981), pp. 234-39.

11. Gerard Braunthal, "The West German Social Democrats: Factionalism at the local level," West\ European Politics 7 (1984).

12. Christian Soe, "A False Dawn for Germany's Liberals." In David Conradt, Gerald Kleinfeldt and Christian Soe, eds. A Precarious Victory (New York: Berghahn, 2004); Emil Kirchner and David Broughton, "The FDP in the Federal Republic of Germany." In Emil Kirchner, ed. Liberal Parties in Western Europe (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989).

13. Soe, "A False Dawn," p. 124.

14. E. Gene Frankland and Donald Schoonmaker, Between Protest and Power: The Green Party in Germany (Boulder: Westview Press, 1993); Margit Mayer and John Ely, eds. The German Greens: Paradox Between Movement and Party (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1998).

15. The average Green deputy was nearly a decade younger than the typical Bundestag member, and 6 of the 10 youngest deputies in parliament belonged to the Greens.

16. Oskar Niedermayer and Richard Stöss, eds. DDR-Parteien im Umbruch (Opladen: Westdeutscher Verlag, 1992).

17. In the West, the Communist party (KPD) suffered because of its identification with the Soviets and the Communist regime of the GDR. The party garnered a shrinking sliver of the vote in early parliamentary elections, and then in 1956 was declared unconstitutional by the courts because of its undemocratic principles. A reconstituted party, renamed the DKP, began contesting elections again in 1969, but was never able to attract a significant following.

18. Susan Scarrow, “Germany: The mixed-member system as a political compromise.” In Matthew Shugart and Martin Wattenberg, eds. Mixed Member Electoral Systems. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001); David Farrell, Electoral Systems, 2nd ed. (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011).

19. Occasionally a party will win more district seats in a state than they are entitled to under strict proportional representation, as the SPD won 9 extra seats in 2005 and the CDU won 7. In this case, the party is able to keep any "extra" seats and the size of the Bundestag is increased.

20. There was a temporary revision of the law in 1990 to allow a party to win 5 percent in either the West or the East in order to receive parliamentary seats. This allowed the PDS to win representation in 1990 and 1994. Today, a party is required to gain 5 percent nationwide.

21. Hans-Dieter Klingemann and Bernhard Wessels, “The political consequences of Germany’s mixed-member system.” In Shugart and Wattenberg, eds. Mixed Member Electoral Systems.

22. Ibid.

23. Russell Dalton, “Partisan Dealignment and Voting Choice." In Stephen Padgett, ed. Developments in German Politics, 4ed ed. (London: Macmillan, 2014).

24. Baker et al., Germany Transformed, ch. 8.

25. Russell Dalton, Citizen Politics, 6th ed. (Washington, DC: CQ Press, 2012), ch. 8; Dalton, "Partisan Dealignment and Voting Choice.”

26. Russell Dalton and Willy Jou, "Is There a Single German Party System?," German Poltics and Society (Spring 2010) 28: 34-52. I recent elections the class alignment in the East has shifted toward the traditional alignment found in the West.

27. Gordon Smith, "The ‘New Model’ party system." In Smith et al., Developments in German Politics.

28. Carsten Zelle, “Social dealignment vs. political frustration,” European Journal for Political Research (1995) 27: 319-345.

29. Hans Mathias Kepplinger. Skandale und Politikverdrossenheit--ein Langzeitvergleich. In O. Jarren et al., Medien und Politische Prozeß. (Opladen: Westdeutscher Verlag, 1996).

30. Richard Von Weizsäcker. Richard von Weizsäcker im Gespräch mit Gunter Hofmann und Werner Perger. (Frankfurt: Eichborn, 1992), p. 164.

31. Gerhard Rieger, ”Parteienverdrosenheit” und “Parteienkritik” in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland. Zeitschrift für Parlamentsfragen 25 (1994), p. 462.

32. Russell Dalton and Steve Weldon, “Public images of political parties,” West European Politics 28/5 (November 2005): 931-951.

33. Ralf Dahrendorf, "Afterword." In Susan Pharr and Robert Putnam, eds. Disaffected Democracies (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005), pg. 311.

copyright 2014

Russell J. Dalton

University of California, Irvine

rdalton@uci.edu

Feb 10, 2014

Angela Merkel has the most unlikely biography for a German chancellor.

She was born in West Germany in 1954, and her father was a leftist-leaning protestant minister who chose to move to East Germany when Angela was 1 year old. Like many young East Germans, she became a member of the communist youth league (FDJ).

She eventually earned a Ph.D. in chemistry from the East Berlin Academy of Sciences in 1986.

Merkel pursued a career as a research scientist, until the GDR began to collapse in 1989.

She first joined the Democratic Awakening and then the CDU, and was elected to the Bundestag as a CDU deputy in 1990.

She rose quickly through the ranks of CDU leaders, serving as Minister for Women and Youth in 1991-94, and Environment Minister from 1994 to 1998.

In 2000 she became the national Chair of the CDU. With her election in 2005, she became the first woman to head the German federal government and the first former citizen of the GDR.

Angela Merkel has the most unlikely biography for a German chancellor.

She was born in West Germany in 1954, and her father was a leftist-leaning protestant minister who chose to move to East Germany when Angela was 1 year old. Like many young East Germans, she became a member of the communist youth league (FDJ).

She eventually earned a Ph.D. in chemistry from the East Berlin Academy of Sciences in 1986.

Merkel pursued a career as a research scientist, until the GDR began to collapse in 1989.

She first joined the Democratic Awakening and then the CDU, and was elected to the Bundestag as a CDU deputy in 1990.

She rose quickly through the ranks of CDU leaders, serving as Minister for Women and Youth in 1991-94, and Environment Minister from 1994 to 1998.

In 2000 she became the national Chair of the CDU. With her election in 2005, she became the first woman to head the German federal government and the first former citizen of the GDR.