| Cognitive Anteater Robotics Laboratory | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

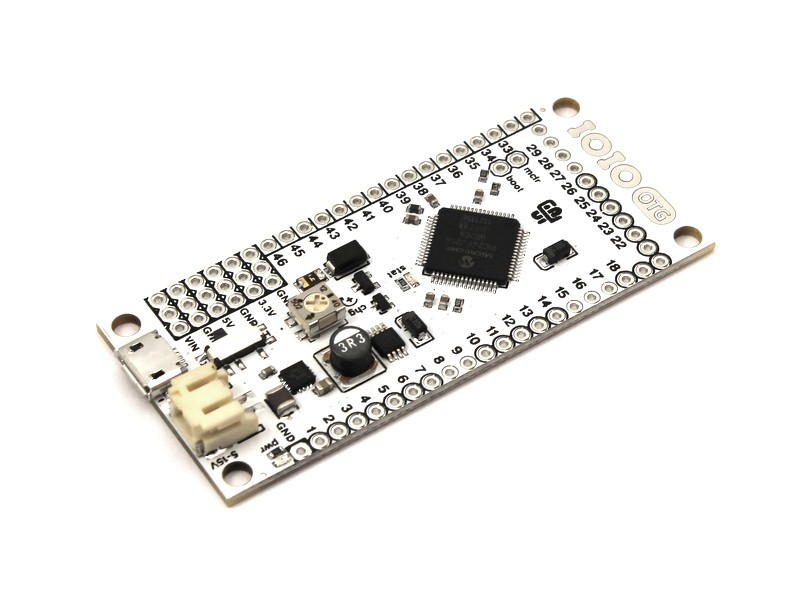

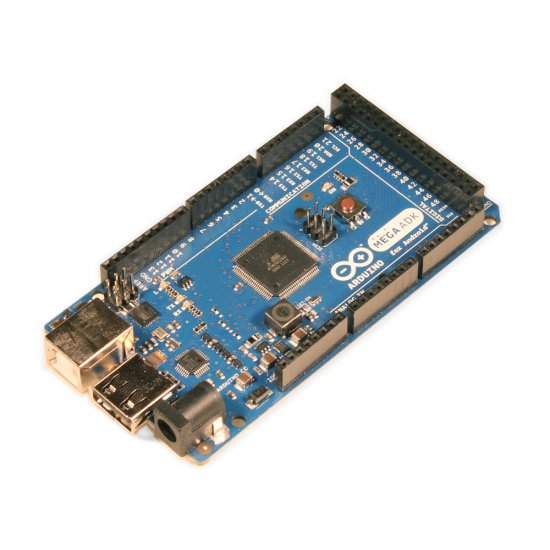

B. Smartphone Based Robots and VehiclesA growing interest in having smartphones interacting with peripheral devices such as motors, servos and sensors led to the recent creation of electronic interface boards that can be purchased online or built at a small cost. These boards serve as communication bridges between Android™ smartphones and external devices. The two main boards available to the public are the IOIO ($30-$39.95) and the Arduino ADK Rev3 (€49.00 ~$65.96), although other boards exist (e.g. Amarino, Microbridge, PropBridge).

Figure 1. IOIO (left) and Arduino ADK Rev3 (right)

For example, a group of hobbyists (Cellbots team) developed open source platforms for Android phones that can be used to control different robotic platforms such as the IRobot Create, Lego Mindstorms, VEX Pro, and Arduino based Truckbot or Tankbot. A group of high school students also built sailboats controlled by Android phones via IOIO boards.These examples show that existing robots can be used as bases, and Android phones as onboard computers. A company called Robots Everywhere develops Open Source control software for Android based robots. A team participated to the RoboCup Search and Rescue Junior competition with an impressive little robot built using an Android phone and a IOIO (rescue robot). Interestingly, some of these projects emerge from developing countries, where the use of Smartphone based robots is attractive due to their low cost and high computational power. For example, a group in Thailand created Android based robots using IOIOs that are fast and can play soccer with ping-pong balls (Android based Soccer Robot).

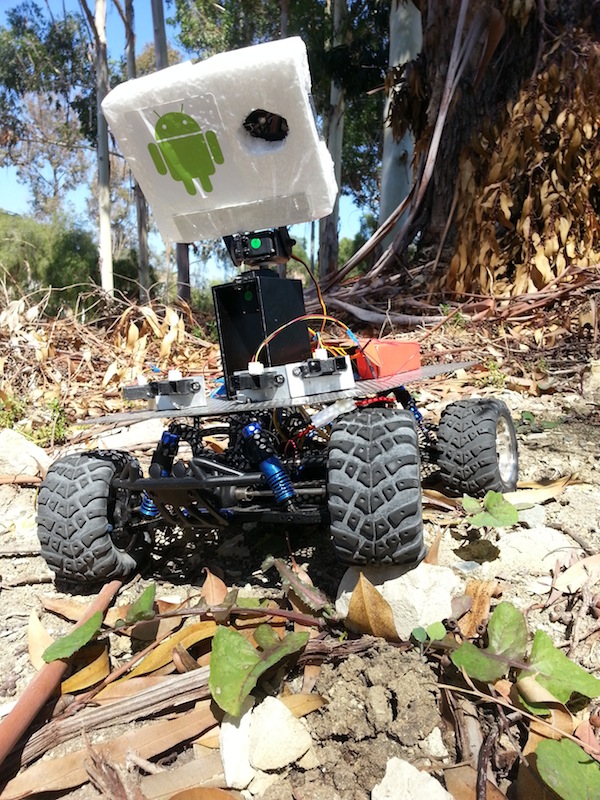

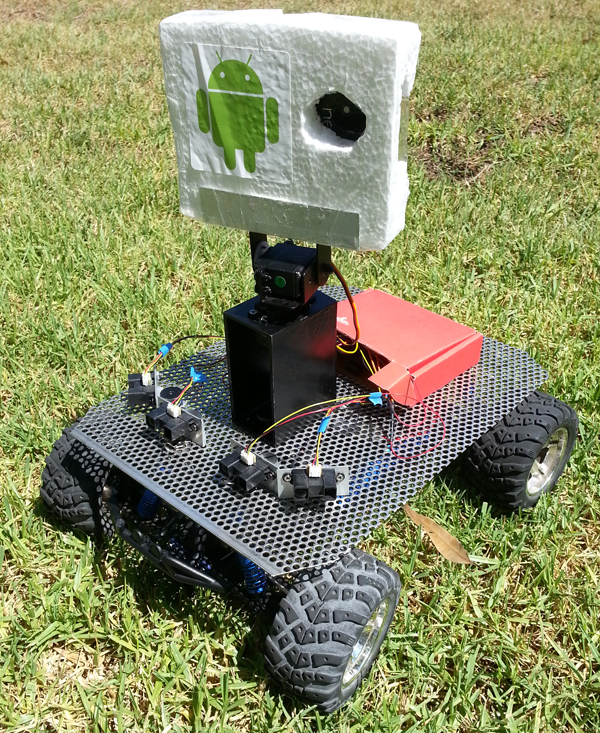

Figure 2. Lego NXT with Android phone (left - Cellbots), sailbots with Android phone (middle - IOIO based), self-balancing robot (right - IOIO based) Our group has built a remote controlled vehicle, named The Android Car, using a R/C car, an Android phone, a phone holder and IOIO. The vehicle can be controlled over Wi-Fi and stream video and sensory information back to a computer (see Table 2 and video below). As will be described later, we are using an upgraded version of this platform for teaching and for research in computational neuroscience. For source code, click here.

Figure 3. NASA Spheres (left), PhoneSat (middle), MIT DragonBOT Smartphone based robots are finding their way into commercial applications (see Table 2). For example, Romo is a small robot using an iPhone as an onboard computer. It can be trained to perform face tracking, controlled using another iOS device over Wi-Fi, or over Internet for telepresence. A simple SDK is also provided to users in order to create their own apps. Similarly, Botiful is a small telepresence robot built for Android phones. Wheelphone is also a small robot that can be used for telepresence. It can also avoid obstacles and cliffs, and find a docking station on its own to recharge its battery. The Wheelphone is compatible with both Android phones and iPhones, and the software is open source and uses ROS and OpenCV libraries. Shimi is a robotic musical companion that reacts to songs played by a smartphone when connected to it. Kibot and Albert are robotic companions that can play with children and help them learn. Although not based on an Android phone, Double is a tall telepresence robot using an iPad as a computing and interacting device. These different companion or telepresence robots are an interesting market. However, they are not modular and not really suitable for many education or research purposes.

Figure 4. Botiful, Romo, Wheelphone II. ANDROID BASED ROBOTIC PLATFORMSimilar to the examples discussed above and in Table 2, our group has developed a smartphone robot platform for hobbyists, students and researchers. We believe our platform provides flexibility over other available options making it attractive to a wide range of enthusiasts. In this section and the next, we describe the components of the platform and instructions on how to construct a smartphone robot.

Figure 5. Example of an Android based Robotic Platform

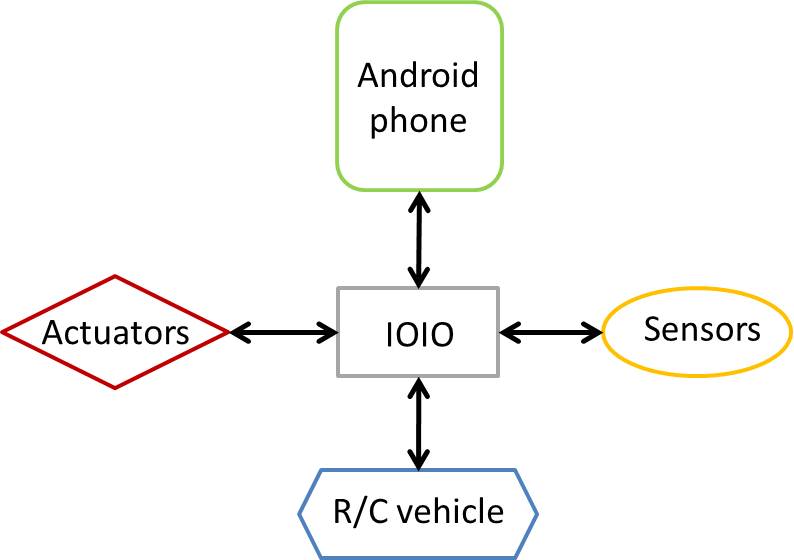

The robot is constructed from an Android phone, IOIO board, which is connected via Bluetooth or USB, a R/C vehicle and additional sensors and actuators.

The robot takes advantage of the sensors on the phone (e.g., camera, accelerometers, GPS), as well as additional sensors

external to the phone (e.g. IR sensors, Hall Effect Sensors) via the IOIO. The Android phone interacts with actuators, such as speed controllers or

pan/tilt units, via the IOIO board.

Our Android Robotic Platform is an inexpensive do-it-yourself (DIY) smartphone based robotic platform using off-the-shelf components and open source software

libraries that could easily be built by students, hobbyists or researchers, but still perform complex computations and tasks.

Figure 6. Diagram showing the main components of the Android based robotic platform and their interactions. The robotic platform gets sensory input from the phone’s internal sensors, as well as external sensors via the IOIO board. The Android phone sends commands to the robot’s actuators via the IOIO board. The Android phone interacts with the IOIO board through a USB cable or a Bluetooth connection. In the following sections, we will describe a robotic platform that can be built for approximately $350 (excluding the phone). The main difference, compared with other smartphone based robots, is that our platform is more modular, and can be used outdoors on uneven terrain. A. COMPONENTS1) Android phone

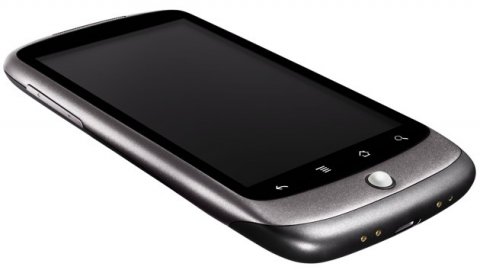

An important advantage of using a smartphone for an onboard computer is that the size of a robot can be kept relatively small, yet still have great features. Its cost can also be minimal since the phone itself can handle computation, sensing and battery power. Many different phones are now available on the market. Before purchasing an Android phone to be used as an onboard computer for a robot, one has to consider the uses and needs of that particular robot. A hobbyist or student may consider using an older less expensive phone. For example, the HTC Google Nexus One can be found unlocked for less than $200, and is a suitable onboard computer. This phone has a 1 GHz Qualcomm Scorpion CPU, 512MB of RAM memory, a microSD card reader (supports up to 32 GB), and a 1400 mAh Li-ion battery. It can provide a number of sensory inputs such as a capacitive touch screen, a 3-axis accelerometer, a digital compass, a satellite navigation system (aGPS), a proximity sensor, an ambient light sensor, push buttons, a trackball and a 5.0 megapixel rear camera with a LED flash. For connectivity, it includes a 3.5mm TRRS audio connector, and hardware supporting Bluetooth 2.1, micro USB 2.0, Wi-Fi IEEE 802.11b/g/n, 2G/3G networks.

Figure 7. Nexus One (left), Samsung Galaxy S3 (right) A researcher may desire more features and computational power. In this case, a recent phone such as the Samsung Galaxy S3 might be considered. This phone can be found unlocked for around $400, has a 1.4 GHz quad-core Cortex-A9 CPU, 1-2GB of RAM, a microSD card reader (supports up to 64 GB), and a 2,100 mAh Li-ion battery. For sensing, it has a multi-touch capacitive touchscreen, 3 push buttons, satellite navigation systems (aGPS, GLONASS), a barometer, a gyroscope, an accelerometer, a digital compass, an 8.0 megapixel rear camera with a LED flash, and a 1.9 megapixel front camera. For connectivity, it includes a 3.5mm TRRS audio connector, and hardware supporting Bluetooth 4.0, Wi-Fi (802.11 a/b/g/n), Wi-Fi Direct, 2G/3G networks, Micro-USB, NFC, and DLNA. Software The Android operating system is open source and Linux-based. Programmers can develop software for Android in Java using the SDK or in native language (C/C++) using the native development kit (NDK) . It is also possible for developers to modify the Linux kernel if needed. Implementation of an Android application can be achieved using the Eclipse IDE with the Android Development Tools (ADT) plug-in. Using this SDK, the developer has easy access to different functionalities of an Android phone such as graphical interfaces, multi-threading, networking, data storage, multimedia, sensors, location provider, speech-to-text, text-to-speech, and more. Since Android phones can connect to the Internet, cloud based applications can also be used when high performance computing is needed. In the field of robotics, this feature can allow the development of cloud based robotics applications. When developing an application that is CPU-intensive but doesn’t allocate much memory, an alternative programming option is to use the Android NDK. With the NDK, a programmer can create an Android Java application that interacts with native code (C/C++) using the Java Native Interface (JNI). Programming in C/C++ on an Android platform can result in an increase of performance, but also increases complexity. The NDK also enables usage of existing C/C++ libraries.

Figure 8. Android SDK (left), Android NDK (right) However, an effort has been made to export popular libraries (e.g., computer vision library OpenCV) to Java so that they can be incorporated in Android applications (OpenCV Android). The robot operating system ROS is also available for Android in Java (ROS Android). It was developed at Google in cooperation with Willow Garage, and enables integration of Android and ROS compatible robots (see Google I/O 2011). Recently, the Accessory Development Kit (ADK) was made available for hardware manufacturers and hobbyists to build accessories for Android. Such accessories use the Android Open Accessory (AOA) protocol to communicate with Android devices, over a USB cable or through a Bluetooth connection (supported from Android 2.3.4).

Figure 9. OpenCV vision library (left), ROS (Robot Operating System - right) 2) Remote-Controlled VehicleThe actuating platform can be kept relatively cheap and small by using an off-the-shelf remote control (R/C) vehicle as a robot chassis. R/C vehicles span a wide range of cost and sophistication and come in many formats. These vehicles can be on-road cars, off-road trucks, tanks, boats, airplanes, helicopters and quad-copters. They can be classified in two main categories: toy grade or hobby grade. The toy grade vehicles are less expensive but also less robust, less powerful, and are harder to modify or repair. Hobby grade R/C vehicles can be purchased in kit, or fully assembled and ready to run (RTR). They can be easily modified and each individual part is accessible and can be replaced. These R/C vehicles provide a speed controller regulating motors and servomotors used for forward or backward movement, and for steering. They are powered by combustion engines (nitro, gas) or electric motors (brushed or brushless) with electric batteries (nickel-cadmium, nickel metal hydride, or lithium polymer cells). Some electric cars can even be powered by solar energy or use hydrogen fuel cells. Compared to typical wheeled robot platforms, R/C cars are affordable, extremely fast, assembled and ready to use, and have hydraulic suspensions that are ideal to minimize vibrations when driving outdoors. This is an important factor to consider when creating a robot supporting a video camera that has to drive on uneven roads, dirt tracks or grass.

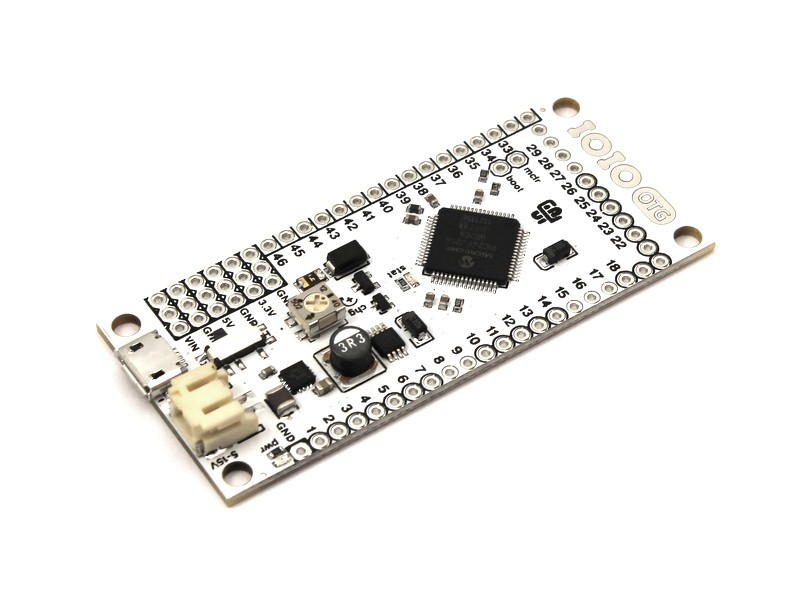

Figure 10. Various remote controlled vehicles 3) IOIOIn order to control a R/C vehicle from an Android phone, we used the IOIO board to link the phone to the motor and servo of the vehicle. The IOIO can send PWM signals to the speed controller of the vehicle in order to regulate its motors and servomotors. The IOIO can also read values from digital and analog sensors, such as infrared sensors (IR) or Hall Effect Sensors. The IOIO provides connectivity to an Android device via a Bluetooth or USB connection and is fully controllable from within an Android application using a simple Java API. The newer IOIO-OTG can also be connected via USB as a host or an accessory to an Android device or a computer. When connected to an Android device, the IOIO-OTG can act as a USB host and supply charging current to the device. If connected to a computer, the IOIO acts as a virtual serial port and can be powered by the host. Compared to the other boards with similar functionality (e.g., Arduino ADK, Amarino, Microbridge, PropBridge), we chose the IOIO because it provides a high-level Java API for controlling the board’s functions without having to write embedded-C code for the board. It supports all Android OS versions, whereas other boards only support the most recent Android OS. The IOIO is inexpensive ($30) with a small footprint (~ 8cm by 3cm), is fully open-source, and has great technical support with an active discussion group and an extensive documentation Wiki.

Figure 11. IOIO board

For more information on the IOIO, go to:

Hardware The main function of the IOIO is to interact with peripheral devices. It can do so with 48 I/O pins, and digital inputs/outputs, PWM, analog inputs, I2C, SPI, TWI, and UART interfaces. The IOIO board contains a single MCU that acts as a USB host and interprets commands from an Android app. The IOIO supports 3.3V and 5V inputs and outputs. It has two on-board voltage regulators. It contains a switching regulator that can take 5V-15V input and output up to 3A of stable 5V, and a linear regulator that feeds off the 5V line and outputs up to 500mA of stable 3.3V. Furthermore, the hardware of the IOIO is fully open source with a permissive license, therefore, the schematics (Eagle files) can be downloaded in order to build the board and even modify it. Software A high-level Java API is provided with the IOIO that provides simple functions to connect to the IOIO from an Android application. The application can read values from digital or analog inputs, and write values to the IOIO outputs. Currently, analog input pins of the IOIO are sampled at 1KHz. Since the IOIO software is fully open source, a developer can perform low level embedded programming in order to modify the firmware for example. Communication between the phone and the IOIO can be made over Bluetooth, or USB using the Android Debug Bridge protocol (ADB) or the more recent Open Accessory protocol. Using the ADB protocol, the one-way average latency is ~4ms and effective throughput is ~300KB/s. Using the open accessory protocol improves the latency to around ~1ms. The jitter (i.e. variance in latency) is also much smaller, and the effective throughput increases to ~600KB/s. Although more convenient, Bluetooth latency is significantly higher than USB (on the order of 10’s of ms), and the bandwidth (data rate) of Bluetooth is significantly lower than USB connections (order of 10’s of KB/sec). 4) Sensors and ActuatorsWhile Android phones provide a large set of sensors and cameras, autonomous robots usually need additional sensors in order to perform a diversity of tasks. Using the Android based platform, robots can be equipped with additional sensors, such as infrared sensors, sonars, touch sensors, whiskers and bumpers. Speed sensors (e.g. using Hall effect sensors) can also be added to the platform when accurate odometry is required. Moreover, gas sensors can be equipped on the robot so it could detect gazes and chemical compounds such as smoke, carbon monoxide, alcohols, propane, methane and more.

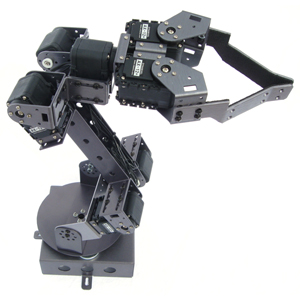

Figure 12. Sensors: infrared, sonar, bump, gas (from left to right) Additional actuators can also be added to our platform in order to perform more complex task. For example, the phone can be mounted on a pan-tilt unit whose servos are controlled by the phone through the IOIO. A robotic arm or gripper could also be mounted on the platform and controlled by the IOIO.

Figure 13. Actuators: pan and tilt unit (left), robotic arm with gripper (right) B. CONSTRUCTION

We will now describe the steps needed to build an Android based robot platform. We built two robots, a small one using a XTM Rage 1/18th 4WD R/C truck ($119.95, max speed: 20 mph), and a larger one using a Hobby People Vertex 4WD 1/10 ($139.95, max speed: 24 mph) R/C truck. For each robot, a sheet of perforated steel was used as a base to support the IOIO, a phone holder, sensors and actuators. The use of a perforated base facilitates the addition, removal and relocation of sensors and actuators on the robot, making the platform highly modular. The IOIO was mounted directly on the base using spacers. We then created mounts for infrared sensors using aluminum angles. These angles were cut and drilled as shown in Figure 14. The IR sensor mounts were screwed to the base using thumbnuts, which enabled their orientation to be easily adjusted. The IR sensors were from the Sharp GP2 series ($14.50) and responded with a voltage proportional to the distance of an object, ranging from 20 cm to 150 cm. Figure 14. Construction phases of mounts for infrared sensors. An aluminum angle was cut and drilled to the dimensions of the IR sensors. Thumbnuts and screws were used to mount the IR sensors to the perforated base. We made a rudimentary phone holder of polystyrene foam and glued it to an aluminum angle perforated to allow the phone holder to be screwed to the base of the robot. While this phone holder might not be the most robust or elegant form factor, it is inexpensive and can be easily built. The phone was actuated by a pan and tilt kit (Lynxmotion $29.93) and mounted on an aluminum rectangular tube. We assembled the servos of the pan and tilt unit, cut the rectangular tube and made a hole to the dimensions of the lower servo. Two holes were drilled on the lower part in order to screw the head to the base. The phone holder was screwed to the pan and tilt unit that was mounted onto the rectangular tube. The head and IR sensors were then mounted on the base of the robot (see Figure 15).

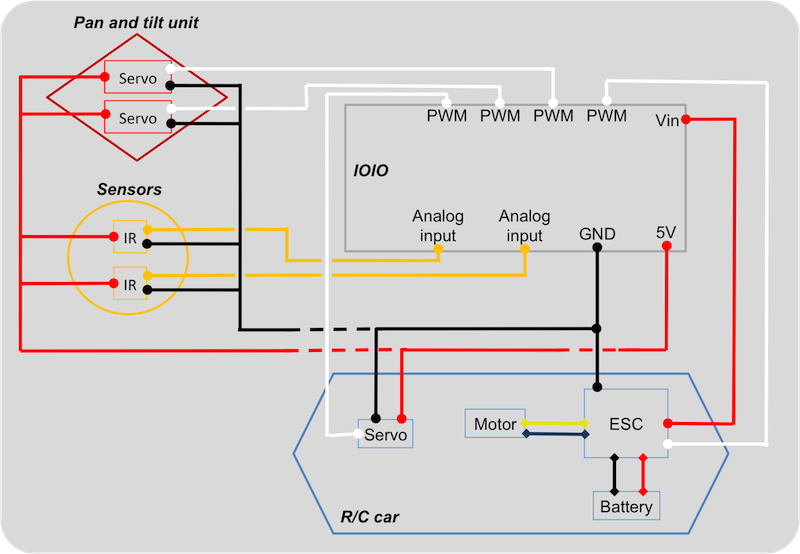

Figure 15. Android based robotic platform composed of IOIO, four infrared sensors, and a robotic head mounted onto a perforated steel base. The base is installed on the chassis of a R/C truck. The robotic head is composed of a rectangular tube, two servos for the pan and tilt unit, and a phone holder made of foam. The electric speed controller (ESC) of the car received power directly from the car’s battery (see Figure 16). We first disconnected the servo and the ESC from the RF receiver on the R/C car. The ESC was then connected to the IOIO to provide power (Vin input) and receive a PWM signal to control the car’s motor (PWM output). The servo of the car was connected to the IOIO that provided power (5V output) and a PWM signal for control (PWM output). The IR sensors were powered by the IOIO (5V) and were connected to the IOIO analog inputs to transmit their values. The servos of the pan and tilt unit also received power (5V) and PWM signals from the IOIO. The IOIO board was connected to the Android phone via USB or Bluetooth. If more sensors and actuators are used, they should be powered separately (not from the IOIO) since the IOIO can only provide 3A maximum on the 5V output pins.

Figure 16. Schematic showing the electrical circuitry of the Android based robot. Sensors and actuators are connected to the IOIO except for the motor of the R/C powered by the ESC. Only two sensors are shown here but more can be added to the platform. We purchased:

NOTE:

C. SOFTWARE

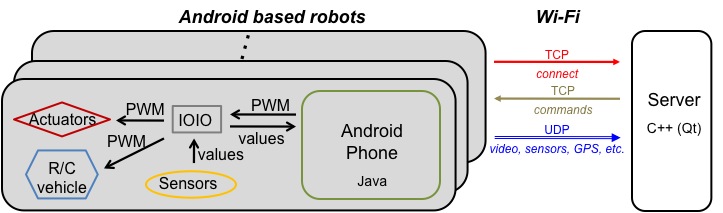

In addition to the Android Robot Platform, we developed software to monitor and control a group of robots deployed in a large area.

Specifically, an Android Java application was created to connect remotely to a server over Wi-Fi. The application captured and sent sensory data

streams (e.g., video, accelerometer, compass, and GPS), and received commands from a host computer.

Figure 17. Schematic of the server-client model of the Android based robots connected to a computer. A phone connects to the server using a TCP socket. Once connected, a user can use the GUI of the server to remotely start or stop threads that control the video camera, sensors, GPS and the IOIO that controls the robot and read sensors values. Data is streamed to the server over different UDP sockets. The pulse width of the PWM signals can also be sent by the server to control a robot remotely.

The Android application was able handle to multiple threads and respond to different sensors with minimal delays. The app’s performance was measured on a

Samsung Galaxy S III by running the app for 5 minutes under four different conditions (see Table 3). First, we recorded the mean update cycles when using

only the camera (see Table 3, I). The camera callback was updated at 21Hz on average and the main thread at 100Hz. In this experiment, the size of each

frame was set to 176 x 144 and the JPEG quality to 75.

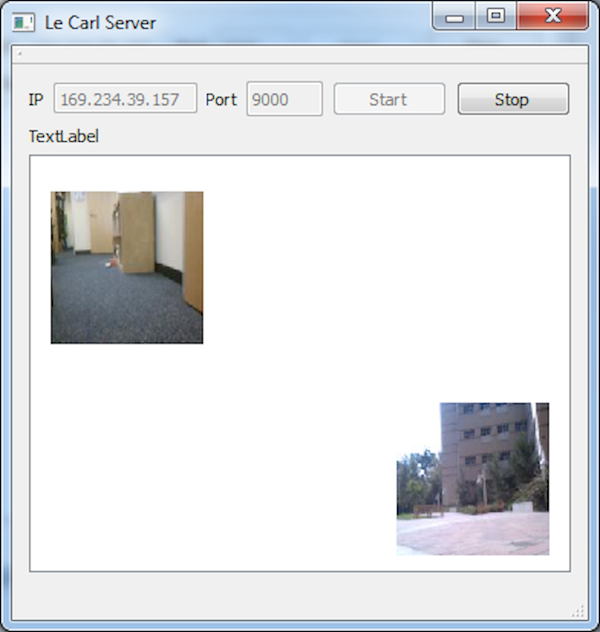

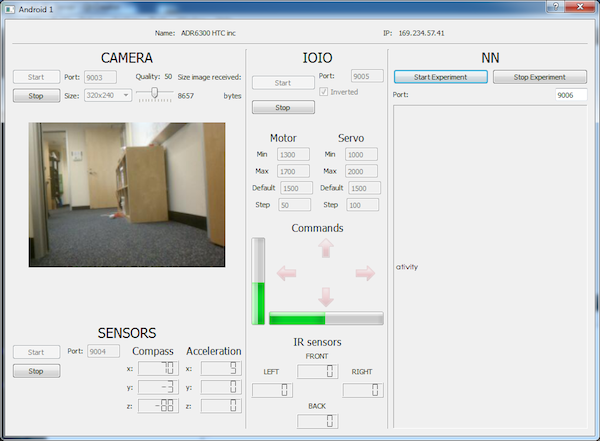

These experiments demonstrated that an app programmed entirely in Java using the Android API, OpenCV and IOIO libraries, could run quite well even when executing many components at the same time. The update frequencies of each component are adequate for robotics purposes. However, we are still working on improving the performance of our app especially for image processing and streaming (e.g. using FFmpeg). We have to emphasize that at this point, we did not try to close programs and services running in the background in order to optimize the scheduling done by the Android OS. Programming certain parts of the app in C/C++ using the NDK should also improve performance. To remotely control multiple robots, monitor their video and sensory information, and allow for direct communication between robots, we developed a C++ application that can run on a desktop computer or laptop (see Figures 17-18). This program was developed using the Qt libraries, and can run on Windows, Mac OS and Linux. A phone can connect to the server using a TCP socket. Once connected, a user can use the GUI of the server to remotely start or stop the video camera, sensors, GPS, and the IOIO in order to read the values of the IR sensors and control the robot. Data is streamed to the server over UDP sockets. Start and stop commands are sent from the server to a phone over the TCP socket. PWM values used to control the robot remotely if needed are also sent over the TCP socket. The server received 20 frames per seconds during experiment I (see Table 3), displaying the video feedback in near real time over Wi-Fi. We had similar results when two phones were connected to the server.

Figure 18. Server program running on a computer. Left - multiple phones/robots can connect to the server and stream data such as video feed. Right - Interface for one robot. Using this window, users can start/stop streaming the video, sensory information coming from the compass, accelerometer, and IR sensors connected to the IOIO. They can also control remotely the robot using the keyboard or allow the robot to run in autonomous mode. More experiments will be conducted in the future to make sure that the program can scale up when connected to more robots. The software (ABR Android app and server program) is available online here. III. APPLICATIONS TO EDUCATION AND RESEARCHIn this section, we describe two applications of our Android Robotic Platform, one developed by students in an undergraduate course on Android programming, and the other developed for computational neuroscience research. These case studies give an idea of the type of applications that can be used with our platform, and highlight the features of the platform. A. Autonomous Android Vehicle

Figure 19. Autonomous Android vehicle tracking and following a green ball transported by a remotely controlled vehicle. The source code, videos and information can be found online here. Their Android application used the camera of a Samsung Galaxy S II, with OpenCV libraries in order to find the contours of a green ball. In their case, commands (PWM signals) were sent from the Smartphone to the R/C car’s speed controller and steering servo through the IOIO, and the IOIO sent the values of four infrared sensors used for obstacle avoidance, to the Smartphone. The pan and tilt unit was also controlled from the IOIO and was used to scan the environment when the robot lost sight of the ball, and to track the ball as it moved. The students also used a second robot that was controlled remotely using a Motorola Droid RAZR and IOIO board. The phone was connected to the IOIO over Bluetooth, and the phone’s accelerometers were used to control the car by tilting the phone in different directions. This car was used to carry the green ball around and be followed by the autonomous robot. The project was a success and confirmed that this platform could be used for education by undergraduate computer science and engineering students. We have to emphasize that the performance of the tracking algorithm used was not of major importance for this project. However, in multiple demonstrations, the follower robot found the leader robot, and tracked it while simultaneously avoiding obstacles. Their project was presented during the AMASE event at UCI which was covered in an OC Register blog: OC register For more information, go to: YesYous B. Android Based Robot Controlled by a Neural Network

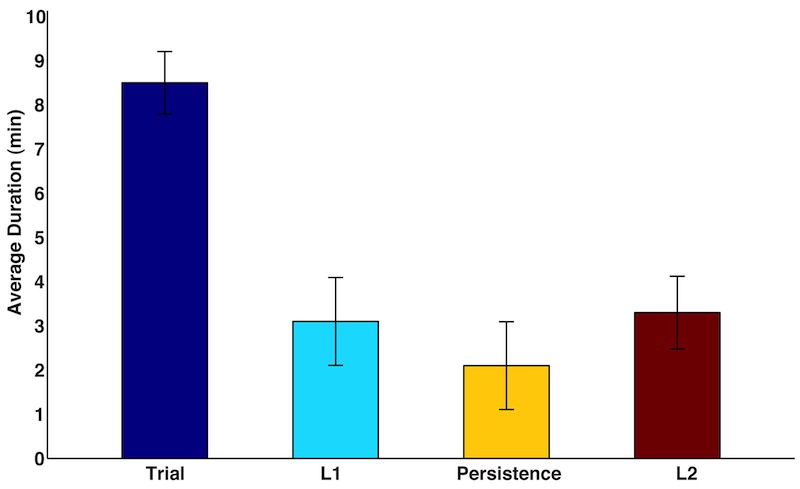

In our instantiation of this task, the Android robot had to learn the locations of valuable resources. The robot had an energy level that decreased over time. After some exploring the robot learned the rewarding location and headed to that location when its energy level was low. The experiment was conducted outdoors on an open grass field where two GPS locations were chosen (L1 and L2) and only one location contained resources (see Figure 20, right). The robot would “consume” resources when it was at the rewarding location. It took three visits to consume all the resources. After the third visit, a reversal was introduced by placing the resources at the other location. The experiment consisted of ten trials and the locations were selected at different places on the open field for each trial.

Figure 20. Left - Android based robotic platform with four infrared sensors and a protection case for the IOIO. Right - open grass field with both locations L1 and L2, where the experiment was conducted.

A neural network running on the Android phone controlled the robot and received the GPS location, compass reading (azimuth) and the values of the IR sensors as

inputs. The neural network was composed of 60 firing rate neurons and 67 synapses (connections). The neural activities and synaptic connections were updated

every 100ms, due to the limitations of the phone used (HTC Incredible 1) and the long update cycles of the GPS (1Hz). It processed the sensory information in

order to learn where the reward was located and select a location to attend to, and outputted the signals controlling the motor and servo of the robot.

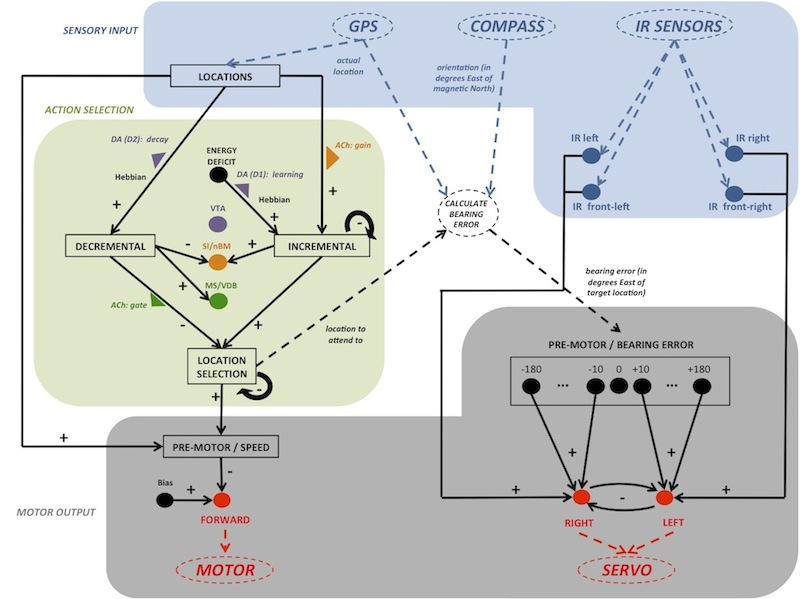

The neural network driving the behavior of the robot was composed of three main groups (see Figure 21): sensory input, action selection and motor output.

See Oros (2012) in PUBLICATIONS for more details.

Figure 21. Neural architecture driving the behavior of the robot. It was composed of three main groups: sensory input, action selection and motor output. Solid line items represent neural implementation (neurons and connections). See Oros (2012) in PUBLICATIONS for more details. The robot successfully performed the task in roughly 8.5 minutes. We set up the experiment so that the robot always started at location L2. The robot initially learned that no resources were present at this location and started to move. If the robot went back to this location again, it would not stop since learned that L2 did not contain a reward. During this time, the robot’s energy level kept decreasing. Once the robot found location L1 where the reward was located, it stopped and stayed still until its energy level was fully replenished. During this time, the robot learned to associate resources with the location L1. Once its energy level was full, the robot started to move again and explore its environment. When its energy level was low, the robot would go back to the location L1 associated with the reward. The robot consumed all the resources present at L1, by visiting L1 three times, in 3.1 minutes on average. A reversal was then introduced by placing resources at location L2. However, the robot persisted in going back to L1 for ~2 minutes until it finally switched back to an explorative behavior. The robot then found and learned that the resources were now at the location L2. As before, when its energy level was low, the robot would go back to the location L2. The robot consumed all the resources present at L2 in 3.3 minutes on average.

Figure 22. Average duration in minutes necessary for the robot to perform the task, and consume all the resources contained at locations L1 and L2. The duration of the robot’s persisting behavior after a reversal is also shown. The mean and standard deviation (error bars) were calculated over ten trials. See Oros (2012) in PUBLICATIONS for more details. In sum, these results show that the robot managed to perform the task in a short amount of time during which it initially learned a stimulus-reward association, and then demonstrated the ability to switch strategy when a reversal was introduced. The robot also exhibited perseverative behavior in accordance with the behavior observed in rats [5, 6] and monkeys [7] performing a reversal learning task. Importantly, for the present article, this work showed that the Android based robot can support complex research projects. The behavior of the robot was entirely driven by a neural network that ran on the phone in real-time, with no previous offline training. The robot managed to perform a reversal learning task successfully by increasing its attention to relevant location and decreasing its attention to irrelevant ones. IV. DISCUSSIONWe presented here a promising trend in robotics, which leverages smartphone technology. These smartphone robots are ideal for hobbyists, educators, students, and researchers. We described different smartphone based robotic projects, and we also demonstrated the relatively easy and inexpensive construction of an Android based robotic platform. Our experience and analyses show that these phones can handle multiple sensors and perform complex tasks in real time. We do want to emphasize that the platform presented in this paper represents only one example of an Android based robotic platform and many different variants exist. Android phones can also be used with other robotic platforms, proving the high potential of using smartphones in robotics (see Table 2, Cellbots). Compared with other smartphone based robotic platforms, our platform is more modular as sensors and actuators can be easily added, removed or relocated on the robot, and it can also be used outdoors. The cost of our platform is also lower than “classical” robotic platforms with similar features and onboard computing power. In the future, the hardware of our platform will be improved by reinforcing the chassis structure, and by adding additional sensors (speed, touch, gas, thermal, etc.) necessary for mapping and for disaster victim identification. Additionally, the use of different chassis (wheels, tracked, or legged vehicles) and steering mechanisms (front wheels steering, differential steering) will be considered.

Figure 23. Android Based Robotic platform. Because of their accessibility and extensibility, we believe that smartphone based robots will be used extensively in many different configurations and environments. For example, the use of inexpensive but capable robots will be highly beneficial for swarm robotics to create a heterogeneous swarm where groups of different robots would carry out different tasks, similar to the Swarmanoid [8]. Our own group is currently working on swarm robotics approaches to search and rescue operations. The overall strategy is to create robots capable of mapping and identifying victims in a disaster zone, and interact with human operators. This robotic swarm could also be modified for environmental monitoring such as pollution or fire detection. The combination of the powerful and efficient hardware of modern Android phones, as well as sensing and interacting devices for robotics, makes Android phones ideal onboard computers. In addition, an API which provides easy access to sensors, cameras, wireless connectivity, text to speech and voice recognition functionalities, open source software and libraries such as OpenCV and ROS, as well as cloud based applications facilitates programming. GPUs on smartphones are also improving rapidly and will soon be adequate to perform more complex algorithms through parallel computation. Furthermore, the low cost and high availability of Android phones make them very attractive for developing countries where Android based robotics will surely boost robotics research and education. To summarize, we believe that Android based robotic platforms will be used extensively for multidisciplinary, innovative and affordable projects in research and education. In addition, this approach to robotics will stimulate the creativity of electrical, mechanical and software engineers, as well as robotics students and hobbyists. ACKNOWLEDGMENTThe authors would like to thank Liam Bucci for assistance in the construction of the Android Based Robotic Platform. The authors also acknowledge students Kevin Jonaitis, Kyle Boos and Joshua Ferguson for their work on the Autonomous Android Vehicle. Finally, the authors would like to thank researchers working at the CARL for useful comments and discussions. PUBLICATIONS

Oros N., Krichmar J.L. 2012. "Neuromodulation, Attention and Localization Using a Novel Android™ Robotic Platform,"

in Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Development and Learning and Epigenetic Robotics (IEEE ICDL-EpiRob 2012), San Diego, USA.

[pdf preprint]

REFERENCES

[1] Y. Ji-Dong, et al., "Development of Communication Model for Social Robots Based on Mobile Service," in Social Computing (SocialCom), 2010 IEEE Second International Conference on, 2010, pp. 57-64.

last updated 27 November 2015 |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||